A-B-Cs of Integrated Weed Management

Farmers successfully use integrated weed management programs across a wide range of situations. It is hard to create a generic “prescription approach” one-size-fits all IWM program because the tactics used are highly dependent on the specific weeds, crops, and field conditions. Understanding the underlying principles of IWM is important to develop strategies for your specific situation.

There is both a science and an art to integrated weed management. The science is outlined in the principles below, which we call the A-B-Cs of weed management. The art is in applying these principles to your specific fields and weeds to create a weed control program that works for you. The principles below are familiar to any crop consultant or Extension agent; use the resources on this page as a starting point to Getting Rid of Weeds in your fields.

A. Know the enemy

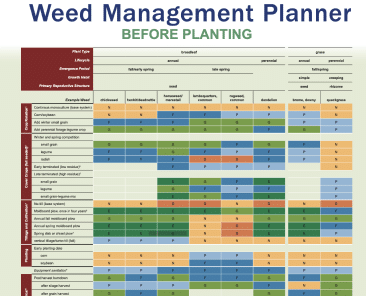

B. Plant into weed-free fields and diversify weed management strategies

Weed Management Planner

C. Actively manage the soil seed bank

A number of attributes contribute to a plant’s “weedy traits” with high seed production and ability to produce seeds under stressful conditions are often described as key characteristics. Producing a large number of seeds often allows a plant species to overwhelm other species.

Seed production, coupled with other seed characteristics, such as dormancy and longevity, allows a species to survive over multiple years in the soil; this reservoir of seeds is often referred to as the soil seed bank. The seed bank is the main source of weeds that ultimately infests agricultural areas and is strongly influenced by cultural practices. The resulting weed populations are quite variable as a result the differential response of weed species to cultural practices.

Stop weed-seed set

Whenever possible, hand pull your escaped weeds before they set seed. As described above, the seed bank size will drastically increase if weeds set seeds.

Manage your field borders with different tactics than in the field. Prevent weed seed set and influx from borders.

In recent years, there have been tremendous efforts to prevent weed escaping control from producing seed within a field to avoid rapid replenishment of the seed soil seedbank and the spread of resistance. However, management must go beyond the borders of the field if growers are to be successful long-term in their fight against weeds.

Stop weed-seed dispersal

Be sure to buy weed-free cash crop and cover crop seed

If you apply manure or other soil amendments, minimize risk of introducing new weeds (e.g. through appropriate composting or testing of materials)

Be sure your soil preparation tools, seeders, and planters are weed-free

Start planning your harvesting sequence, leaving weedy fields for last as well as infested areas within a field.

For more information go to our page: Prevent Weed Seed Dispersal at Harvest, A Simple Plan

Plan your harvest sequence and logistics in advance.

Consider the machinery needed for harvest and plot out movement through your fields from least weed infested to most. Know where you will clean your combine once ready to harvest and allow time to clean it to prevent the spread of weeds.

If you plan to hire harvest contractors, be sure they thoroughly clean their machinery before coming into your fields and when moving between fields. If you buy used combines, be sure to clean them thoroughly.

When you move your combine and support tools from one field to another, do a thorough cleaning before running them in the next field to be harvested. Watch this video to help deep clean your combine of weed seeds.

Along with thoroughly cleaning field machinery, implement Harvest Weed Seed Control

Weeds that escape control are likely to be mature at the time of crop harvest; the erect seed heads will likely enter the combine harvester. Harvested weed seeds are expelled from the rear of the combine, resulting in their dispersal across the field to become additions to the soil seedbank, a process that increases the risk of herbicide resistance evolution. Seed production of annual weeds persisting through cropping phases replenishes/establishes viable seed banks from which these weeds will continue to interfere with crop production. Harvest weed seed control (HWSC) is an Australian innovation that is now viewed as an effective means of interrupting this process by targeting mature weed seed, preventing seed bank inputs by many major weed species. However, the efficacy of these systems is directly related to the proportion of total seed production that the targeted weed species retains (seed retention) at crop maturity. Weed species with a level of seed retention are good candidates for HWSC. HWSC methods include:

1. Chaff Carts to remove weed seeds contained in the chaff fraction from the fields in bales;

2. Narrow windrow burning, which consists of making narrow chaff rows behind the combine then burning them to eliminate weed seeds, and

3. Impact mills, which are built-in machines that fit inside the combine and destroy weed seeds during crop harvest.

4. Chaff lining and chaff tramlining, takes a chute and diverts only the chaff fraction into a narrow row in the center of the harvester, while the rest of the crop residue is spread evenly behind the combine. While weed seeds are returned to the soil, they are in narrow lines instead of being spread across the entire field. The chaff material is allowed to rot and decay. These lines could be treated differently, using targeted herbicides sprays, or managed with different tools at a site specific level.

5. Bale-direct system: consists of a large square baler that is attached directly to the harvester which constructs bales from the chaff and straw residue.

Authors

- Michael Flessner

- Kara Pittman

- Claudio Rubione

- Mark VanGessel

Contributors

- Victoria Ackroyd

- Lovreet Shergill

- Steven Mirsky

Resources

- A Practical Guide for Integrated Weed Management in Mid-Atlantic Grain Crops is a new guide, written by scientists from 5 universities and the USDA, explaining different weed management tactics and includes a scenario of how to implement an IWM program through the lens of grain production in the Mid-Atlantic region. Note: Consult your local Extension Agent, Certified Crop Advisor (CCA), or other specialized professional for customized advice specific to your needs and goals.

Citations

- Doucet C, Weaver SE, Hamill AS, Zhang J (1999) Separating the effects of crop rotation from weed management on weed density and diversity. Weed Sci 47:729-735.

- Lazaro L, Norsworthy JK, Walsh MJ, Bagavathiannan MV (2017) Efficacy of the Integrated Harrington Seed Destructor on weeds of soybean and rice production systems in the Southern United States. Crop Sci 57:2812-2818.

- Liebman M, Dyck E (1993) Crop rotation and intercropping strategies for weed management. Ecol Appl 3:92-122.

- Mohler CL. The role of crop rotation in weed management. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education. https://www.sare.org/Learning-Center/Books/Crop-Rotation-on-Organic-Farms/Text-Version/Physical-and-Biological-Processes-In-Crop-Production/The-Role-of-Crop-Rotation-in-Weed-Management.

- Accessed: October 29, 2019. Norsworthy JK, Korres NE, Walsh MJ, and Powles S (2016) Integrating herbicide programs with harvest weed seed control and other fall management practices for the control of glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth ( Amaranthus palmeri ). Weed Sci 64:540-550.

- Wallace J, Lingenfelter D, VanGessel M, Johnson Q, Vollmer K, Besancon T, Flessner M, Chandran R (2019) 2019 Mid-Atlantic Field Crop Weed Management Guide. University Park, PA: Penn State Ag Communications and Marketing.

- Walsh MJ, Aves C, Powles S (2017) Harvest weed seed control systems are similarly effective on rigid ryegrass. Weed Technol 31:178-183.

- Walsh MJ, Powles SB (2014) High seed retention at maturity of annual weeds infesting crop fields highlights the potential for harvest weed seed control. Weed Techol 28:486-493.

- VanGessel M, ed (2019) A Practical Guide for Integrated Weed Management in Mid-Atlantic Grain Crops. https://growiwm.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/IWMguide.pdf?x71059 Accessed: October 29, 2019

This material was written by: Michael Flessner, Kara Pittman, Claudio Rubione, Mark VanGessel, Victoria Ackroyd and Lovreet Shergill.

Get Rid of Weeds: Act proactively

Note : Consult your local Extension Agent, Certified Crop Advisor (CCA), or other specialized professional for customized advice specific to your needs and goals.