The following is reprinted with permission from Penn State Extension.

Cover crops can be challenging to establish after soybeans. One way to get cover crops established sooner is broadcast-seeding covers into standing soybeans prior to harvest. This can be done from the ground or aerially with a variety of equipment.

Phase 1, 2020-2022: Seeing if broadcasting into standing beans can work

We initiated a study with support from the Pennsylvania Soybean Board in 2020 to examine viable cover crop species for broadcasting into standing soybeans. Nine species were chosen: cereal rye, winter wheat, annual ryegrass, red clover, crimson clover, Balansa clover, hairy vetch, rapeseed, and forage radish. Cover crops were established between R6, or the “green bean” stage, and leaf drop.

Nine site-years, including 5 cooperating farms, were evaluated between 2020-2022. Except for one site-year (York, 2021), Dry matter production was very low (<1,000 lb/ac). Clovers produced a maximum of 200 lb/ac biomass only when termination was delayed into June. Small grains were the most productive species at all sites where they were included but grew less than 700 lb/ac at 7 of 9 site-years. Hairy vetch performed marginally well in the southeast, producing less than 500 lb/ac; however, establishment was very patchy, and weeds outweighed the vetch in most plots.

The NRCS recommends at least 2,700 lb/A of cover crop dry matter to really see cover crop benefits, so we likely did not see significant benefits from the cover crops at most sites. Groundcover and plant density counts followed similar trends to spring biomass, and even the highest spring density was less than half the plants/A recommended by NRCS.

The first two years of the study showed inconsistent establishment and that success depends greatly on timely rainfall with this method. Planting should be targeted for mid-late September in the southeast, and earlier further north in the state. We found small grains and annual ryegrass to be most successful with potential for hairy vetch and rapeseed in the southeast, and recommend avoiding clover species for this practice. We also concluded that it is best suited for fields where cover crop termination is delayed into late May or June.

Phase 2, 2022-2023: How does broadcasting cover crops compare to drill-seeding?

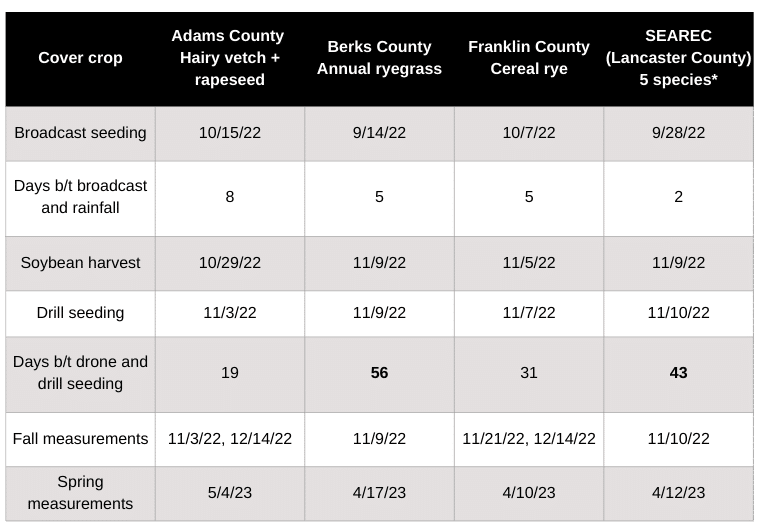

The second phase of this trial, seeded in fall 2022, compared broadcasting the most successful species from phase one (cereal rye, winter wheat, annual ryegrass, hairy vetch, and rapeseed) with drill-seeding after soybean harvest.

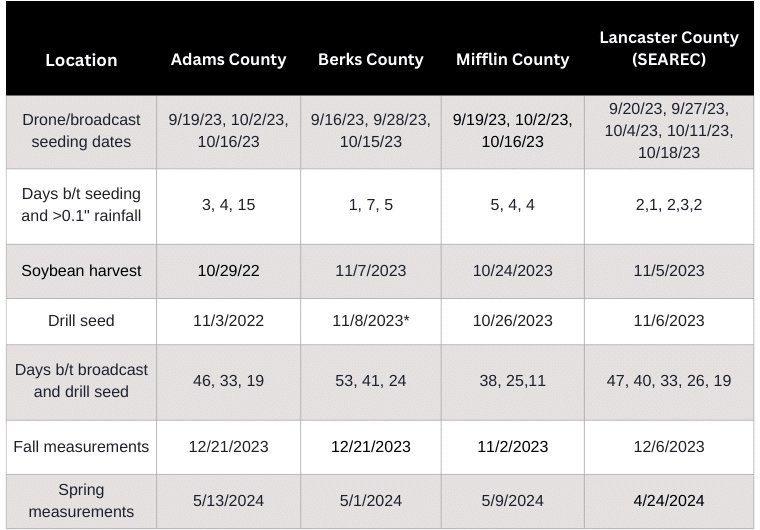

Second Phase Site Information

Broadcast seeding provided significantly higher cover crop density and biomass at termination than drill-seeding at Berks (409 lb/ac and 0 lb/ac, respectively) and Lancaster Counties (643 lb/ac and 302 lb/A, respectively, Figure 2). There was no difference in hairy vetch biomass between establishment methods at Adams County (616 lb/ac and 555 lb/ac, respectively), but broadcast seeding provided higher hairy vetch density than drill-seeding; rapeseed didn’t establish at the Adams County site for either method. Drill-seeding cereal rye out-performed broadcast seeding for all measures at the Franklin County site (589 lb/ac and 211 lb/ac, respectively).

Despite broadcast seeding performing better this year than in prior years, likely due to early seeding in combination with timely rainfall, the maximum biomass achieved at any site was 1,220 lb/ac at SEAREC, still below the recommended NRCS minimum. Delaying termination until early May could have helped reach the 2,700 lb/ac threshold, but delaying termination is not a standard practice in the area.

These data provide evidence that broadcast seeding into soybeans can be as successful or more successful than drill-seeding after soybean harvest, but broadcasting must be done early, preferably by the end of September in this region. We found that there is a larger benefit to broadcast seeding the later drill seeding gets.

Phase 3, 2023-2024: How does drone seeding cereal rye into soybeans compare to drill-seeding?

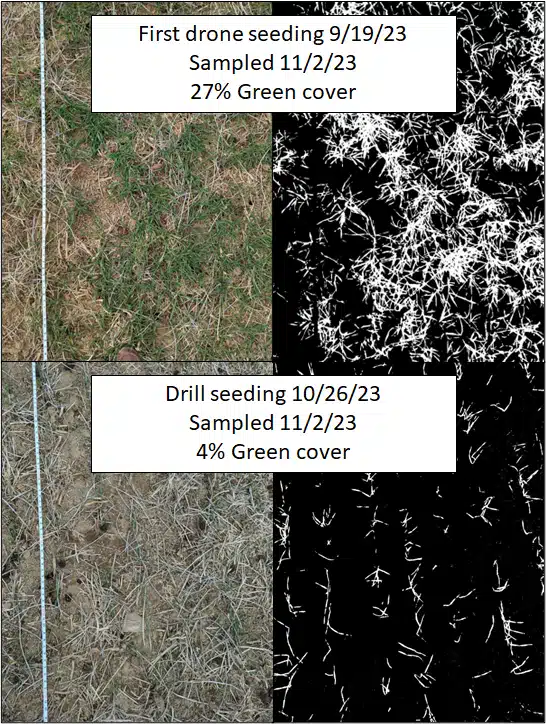

The third phase of the trial, seeded fall 2023, compared three different dates of drone-seeding cereal rye with drill-seeding after soybean harvest.

Drone service was provided by Swift Aeroseed, LLC out of Carlisle, PA. Cereal rye was seeded at approximately 80 pounds per acre at all cooperator locations. We attempted to time seeding starting at the initiation of leaf yellowing, and every other week for three total drone seeding dates. Post-harvest drill-seeding was done by cooperator farmers with their own equipment, as soon as possible after soybean harvest. At SEAREC, a chest-mounted spinner spreader was used to seed 120 pounds per acre of rye into standing soybeans weekly for five weeks leading up to soybean harvest. A 10-foot drill was used to seed 120 pounds per acre after soybean harvest.

We took similar measurements to prior years; soil nitrate (0-6 inches), cover crop density (plants per square foot), and groundcover (percent) in the fall and spring, and cover crop biomass (pounds per acre) in the spring.

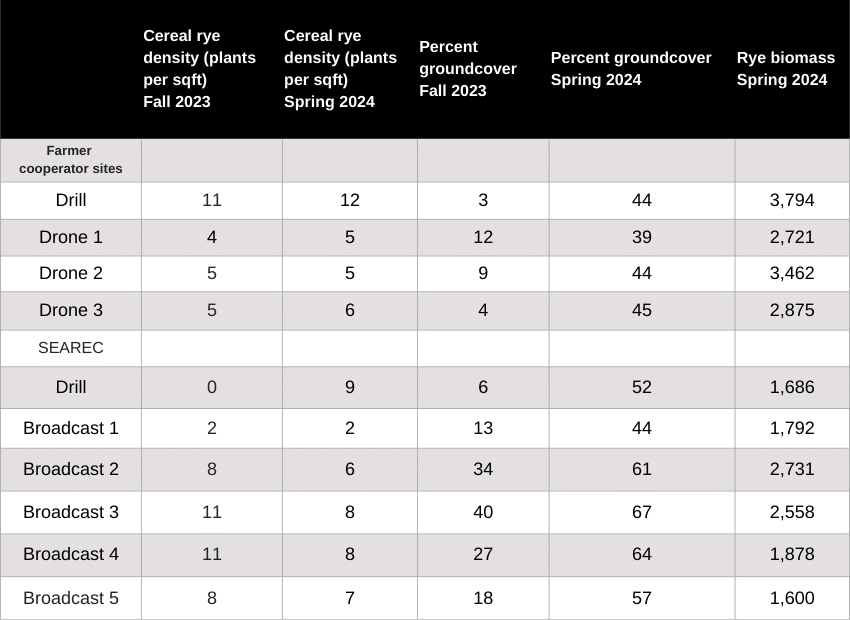

Third Phase Site Information

At cooperator sites, cereal rye density was highest in the drill seeded treatment in both the fall and spring. Groundcover, as measured with the Canopeo app, was higher the earlier the cover crop was seeded (see data in table below). However, by spring sampling, there was no difference between seeding dates or methods. Cereal rye biomass was maximized by drill seeding after soybean harvest (3,462 pounds per acre dry matter), or drone seeding at the second planting date (3,794 pounds per acre dry matter), or between September 28 and October 2.

Third Phase Results

At SEAREC, Groundcover and rye density trended highest at the third seeding date, October 4. However, differences were minimal by spring. Similar to the cooperator sites, broadcasting between September 27 (2,731 pounds per acre dry matter) and October 4 (2,558 pounds per acre dry matter) resulted in significantly higher biomass than other planting dates, including drill-seeding after soybean harvest (1,686 pounds per acre dry matter).

We once again found across all sites that planting date and method had no impact on soil nitrate, likely due to these minimal differences in cover crop establishment and spring biomass accumulation. We did observe that planting date appeared to have some impact on spring development, and earlier-seeded treatments matured earlier than later seedings.

In conclusion, the greatest benefit to drone seeding the rye was quicker groundcover in the fall, with minimal impact on biomass production or spring groundcover. It does appear that cereal rye can be seeded into soybeans too early, and we would recommend waiting until the last week of September or first week of October to time seeding. However, there is no benefit to broadcasting cereal rye into standing soybeans if it is done within one month of soybean harvest and post-harvest seeding (if drilled or broadcast/incorporated).

We will continue to work on establishing best practices for broadcast or seeding other species into standing soybeans, such as annual ryegrass, hairy vetch, and canola. Ground rigs and drones each come with their own benefits and challenges, but in most aspects both methods of broadcasting into standing soybeans behave similarly.

For more information on the project, or to become a cooperator on this project, please reach out to Heidi Reed.

See a GROW video of Heidi presenting this research at a field day below:

See this article on Penn State Extension’s website here.

Article and feature photo by Heidi Reed, PSU Agronomy Educator; video by Claudio Rubione, GROW; header photo by Rachel Vann, NCSU/Science for Success