Cyperus esculentus L.

Also known as: chufa, nutgrass, watergrass

Often cited as one of the “world’s worst weeds,” yellow nutsedge is a perennial weed, spreading primarily through rhizomes and tubers (often referred to as nutlets), and has bright yellow spikelet seedheads. Yellow nutsedge is found in nearly every region of the United States and can invade row crop fields, pastures, lawns, and horticultural or nursery areas. Having a triangular stem and smooth, almost “waxy”, narrow leaves, yellow nutsedge can sometimes be misidentified with other sedges. Correct identification is key to deploying proper management of yellow nutsedge.

Identifying Features

Yellow nutsedge is a perennial weed with smooth, light green triangular stems that grow upright and can reach 30 inches in height in some situations. Yellow nutsedge can be mistaken for purple nutsedge, but yellow nutsedge is often larger, and the leaves come to a much sharper point than purple nutsedge.

Yellow nutsedge can be found across the U.S. and southern Canada, thriving in temperate regions, while purple nutsedge’s range is more limited to the southern U.S. and the tropics due to lack of cold tolerance. Yellow nutsedge reproduces primarily via underground tubers or nutlets, which form underground at the ends of rhizomes. A single plant can produce several hundred orange/brown nutlets.

Once established, nutlets can remain viable in the soil for more than 3 years. Although yellow nutsedge does produce a distinctive seedhead, seed production plays a minor role in its persistence. Shoot emergence occurs from late spring to early summer, with some later shoots emerging from tillage events. Newly emerged shoots from tubers are often large and vigorous, quickly outcompeting surrounding vegetation. Yellow nutsedge will spread rapidly and persist without effective management, making long-term control challenging. One tuber of yellow nutsedge planted in a field study produced 36 plants and 332 tubers in 16 weeks.

Yellow nutsedge is well-adapted to a wide range of climates and soils, but it grows best in low-lying areas, poorly drained fields, and along ditches or pond banks. Infestations often begin in these wet environments and gradually spread into drier parts of a field.

Seed Production

The seed head of yellow nutsedge consists of yellow, multi-stalked clusters of spikelets. The seeds are light brown and typically have poor germination. Around 90% of yellow nutsedge populations fail to produce seeds, but those that do can average 1,500 viable seeds per flower. Since seed production is rare and seeds have low germination, yellow nutsedge primarily spreads via the transport of tubers or the spread of rhizomes.

Herbicide Resistance

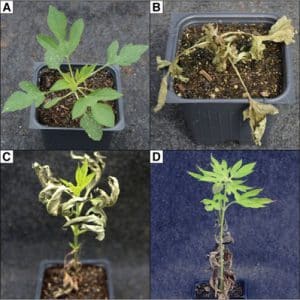

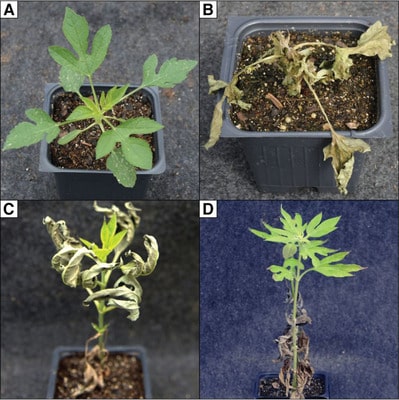

Yellow nutsedge populations in Arkansas and Georgia have resistance to the Group 2 herbicides (acetolactate synthase inhibiting herbicides – ALS). These populations were discovered between 2015 and 2020. The Arkansas population was found to be cross-resistant to four different ALS-inhibiting chemical families, while the Georgia population had a narrower resistance spectrum, limited to the imidazolinone family.

Integrated Weed Management Options

While herbicides are the most common and effective tool to manage yellow nutsedge in our major row crops and in turfgrass, overreliance and repeated selection pressure have allowed for the evolution of herbicide-resistant biotypes. An integrated weed management plan that combines chemical, cultural, and mechanical tactics is most effective for the prolonged management of yellow nutsedge. Developing an integrated weed management plan may reduce selection pressure from herbicides and impart multiple stressors throughout the life cycle of yellow nutsedge.

Crop Rotation

Including highly competitive crops that can outcompete yellow nutsedge in a rotation may help reduce yellow nutsedge populations to a manageable level. Consider planting crops that are planted in the fall (winter annuals) or early spring, so a canopy is established before yellow nutsedge shoot emergence. Crop rotations that allow effective herbicide control can reduce populations prior to rotating to crops with limited herbicide options.

Tillage

Yellow nutsedge is sensitive to tillage, particularly early in the growing season. Repeated tillage events can reduce underground energy storage and lead to weaker, less competitive shoots. These weaker shoots will then likely be more easily suppressed by the crop.

Mulch

Yellow nutsedge is difficult to suppress with mulch because the energy stored in its underground tubers allows it to push through many materials, including wood chips and even thin polyethylene mulch commonly used in vegetable production. However, thicker polyethylene mulch is more effective as a cultural control practice. Research indicates that black opaque mulch can reduce shoot emergence by about 47%, while clear plastic mulch can reduce emergence by up to 72%. The improved suppression with clear plastic mulch occurs because light penetration stimulates leaf expansion, which blunts the shoot tips and lowers their ability to puncture the mulch.

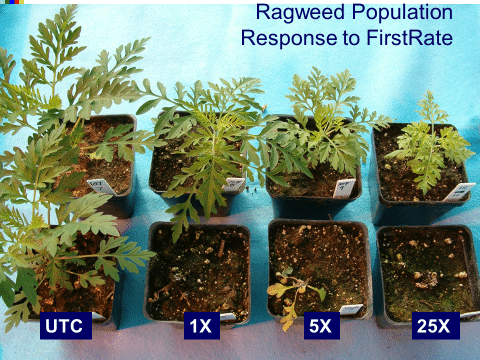

Herbicide Control Options

Below are some labeled herbicide options that have been reported to achieve ≥80% control of yellow nutsedge. Each application timing is in relation to the specified crop. Always refer to the label before making any applications.

Resources

https://www.nwcb.wa.gov/weeds/yellow-nutsedge

https://extension.psu.edu/lawn-and-turfgrass-weeds-yellow-nutsedge-cyperus-esculentus

https://yardandgarden.extension.iastate.edu/faq/how-do-i-control-yellow-nutsedge-my-lawn-and-garden

https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/encyclopedia/yellow-nutsedge

Citations

Anderson, WP Purple nutsedge, Yellow nutsedge pages 57 to 66 IN Perennial Weeds-characteristics and identification of selected herbaceous species 1999 Iowa State University Press

Bendixen, L. E. (1973). Anatomy and Sprouting of Yellow Nutsedge Tubers. Weed Science, 21(6), 501–503. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0043174500032343

DEFELICE, M. S. (2002). Yellow Nutsedge Cyperus esculentus L.—Snack Food of the Gods 1 . Weed Technology, 16(4), 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1614/0890-037x(2002)016[0901:yncels]2.0.co;2

Johnson, W. C., Davis, R. F., & Mullinix, B. G. (2007). An integrated system of summer solarization and fallow tillage for Cyperus esculentus and nematode management in the southeastern coastal plain. Crop Protection, 26(11), 1660–1666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2007.02.005

Lindell, H. C., Prostko, E. P., McElroy, S., Patel, J. D., Blankenship, J. D., Grey, T. L., & Basinger, N. T. (2024). Evaluation of ALS-resistant yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) in Georgia peanut. Weed Science, 73. https://doi.org/10.1017/wsc.2024.87

Mohler, C. L., Teasdale, J. R., & Ditommaso, A. (n.d.). MANAGE WEEDS ON YOUR FARM A GUIDE TO ECOLOGICAL STRATEGIES. www.sare.org/manage-weeds-on-your-farm

Tehranchian, P., Norsworthy, J. K., Nandula, V., Mcelroy, S., Chen, S., & Scott, R. C. (2015). First report of resistance to acetolactate-synthase-inhibiting herbicides in yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus): Confirmation and characterization. Pest Management Science, 71(9), 1274–1280. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.3922

Webster, T. M. (2005). Mulch type affects growth and tuber production of yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) and purple nutsedge (Cyperus rotundus). Weed Science, 53(6), 834–838. https://doi.org/10.1614/ws-05-029r.1

Yu, J., Sharpe, S. M., & Boyd, N. S. (2021). Sorghum cover crop and repeated soil fumigation for purple nutsedge management in tomato production. Pest Management Science, 77(11), 4951–4959. https://doi.org/10.1002/PS.6537

Author

Ryan Hamberg, Texas A&M University

Editors

Emily Unglesbee, GROW

Mark VanGessel, University of Delaware

Michael Flessner, Virginia Tech

Muthu Bagavathiannan, Texas A&M University

William Curran, Penn State University (emeritus)