Biological Control of Weeds

Most methods of biological weed management, also known as biocontrol, use naturally occurring, living organisms to decrease weed abundance. These methods do not eradicate the target weeds but rather exert pressure on them to reduce their populations to more acceptable and manageable levels. They tend to be long-term actions and only work with certain weed species. Biocontrol of weeds is most often used on perennial and biennial species in natural areas, rangelands, and other perennial ecosystems. It is less common in conventional annual cropping systems where crop rotation, harvest, and soil disturbance can more easily disrupt biocontrol organisms.

There are four main methods of biological weed control:

- Classical: An organism (often non-native, but sometimes native) is released into areas infested with the targeted weed, and the biocontrol organism sustains itself by feeding on or infecting the weed and reducing the weed population over time. These biocontrol organisms are intended to be very host-species specific.

- Inundative: An organism is released or applied to control the target pest. Mass release of insects to overwhelm the pest or applying a bioherbicide both fit this category of “inundating” the pest. These techniques are intended for relatively quick and shorter-term control, and release or application can occur multiple times.

- Conservation: A cropping system is manipulated to increase the populations of natural weed-suppressing organisms.

- Grazing: Herbivores such as cattle or sheep are used to reduce weed populations.

1. Classical Biocontrol

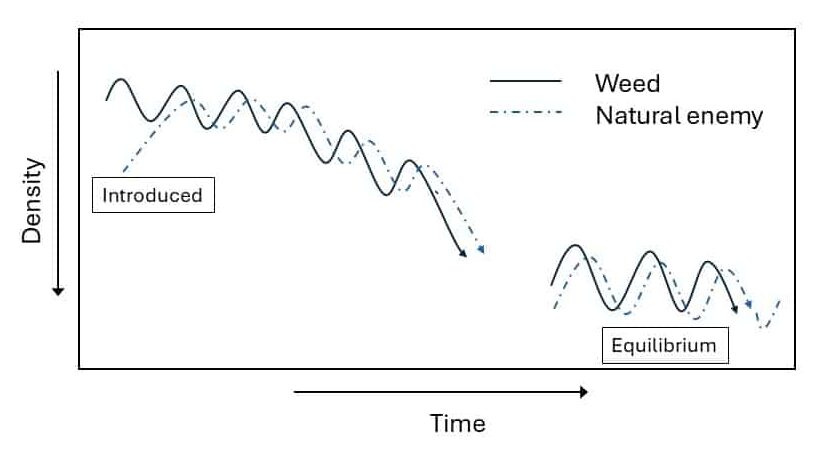

The classical biocontrol approach involves releasing a specific biological agent, such as an insect, fungus, bacterium or virus to a weed-infested area and allowing the agent to increase in number and attack the weeds. This approach often requires finding biocontrol organisms in the weedy plants’ home range, evaluating their potential use, and then importing and releasing them. The selected biocontrol agent must be very weed species specific and not target anything considered beneficial or native. This can take many years and requires passing numerous testing and regulatory requirements. If approved and permitted through USDA-APHIS, this classical approach for biological control often requires multiple seasons for the impact to be evident. Once established, it is common for the biocontrol organism and the pest species to cycle back and forth in abundance over time (see Figure 1). In theory, the pest and natural enemy will reach some type of equilibrium or balance.

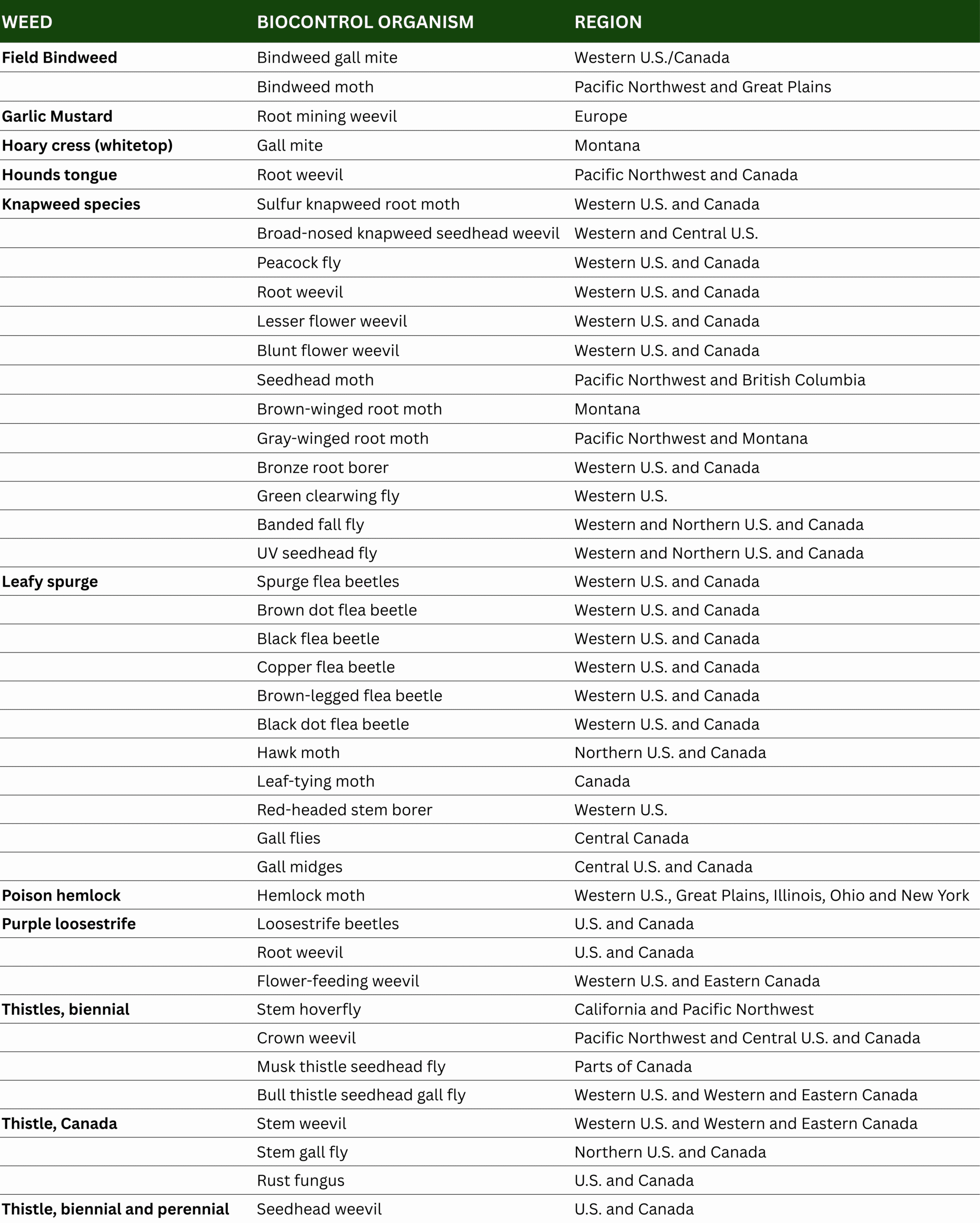

Classical Biocontrol in the Field. Cactoblastis cactorum, a moth released in 1926 to reduce prickly pear cactus in Australia, and the Chrysolina beetles released in the 1940’s that reduced St. John’s Wort (Klamath weed) in California, are two older success stories of classical biocontrol methods. Today, many beetles, caterpillars, mites, weevils, and other insects continue to be pursued, examined, and potentially released for suppression of perennial and biennial thistles, leafy spurge, dalmatian and yellow toadflax, the knapweeds, purple loosestrife, salt cedar, and many other weeds (Table 1). Pathogens including fungi, bacteria, and viruses can also be successful biocontrol candidates. Of these microbes, fungi have been most successful, and several different organisms show potential for control of problem invasive weeds. Most recently, researchers in the West are exploring use of a Canada thistle rust pathogen to manage that troublesome weed. (See more on this in Accordion 5)

Several western U.S. states have active classical biocontrol programs often affiliated with universities, state departments of agriculture, and the federal government. As examples, Colorado has the Colorado Department of Agriculture Palisade Insectary and Montana, the Montana Biocontrol Coordination Project. States outside the west also have biocontrol programs, including Florida with substantial efforts in management of invasive aquatic species.

2. Inundantive or Augmentative Biocontrol

With inundative or augmentative biocontrol, the organism is applied or released on a large scale to achieve a rapid reduction in the target pest. For weeds, this type of biocontrol often takes the form of a myco- or bio-herbicide made from a plant-pathogenic fungus that can be applied like conventional herbicides. Many products have been examined, and some have been commercialized over the last 30 years; however, many are no longer available because of cost of production, lack of efficacy, or both.

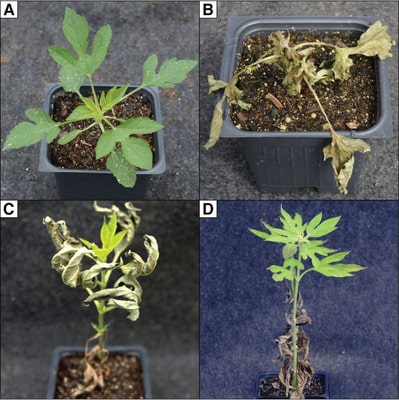

Successful commercial products include Collego, introduced in 1982 as a formulated mycoherbicide from the fungus Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene. It is still used to control northern jointvetch, a problem weed of rice in the southern US. SolviNix was commercialized in 2014 and is made from a plant virus (tobacco mild green mosaic virus) that targets tropical soda apple. The technology was developed by the University of Florida and licensed to BioProdex, Inc. and continues to be evaluated. Lastly, Bio-phoma is a fungal product (Phoma macrostoma) introduced in 2016 that helps control several weeds including Canada thistle and dandelion. It is a granule applied to the soil, but application rate and cost have limited adoption. Evologic, an Austrian-based biological products company has been improving Phoma and hopes to soon introduce a product for large-scale agricultural use.

3. Conservation Biocontrol

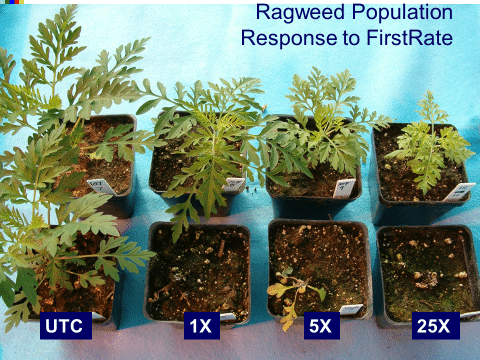

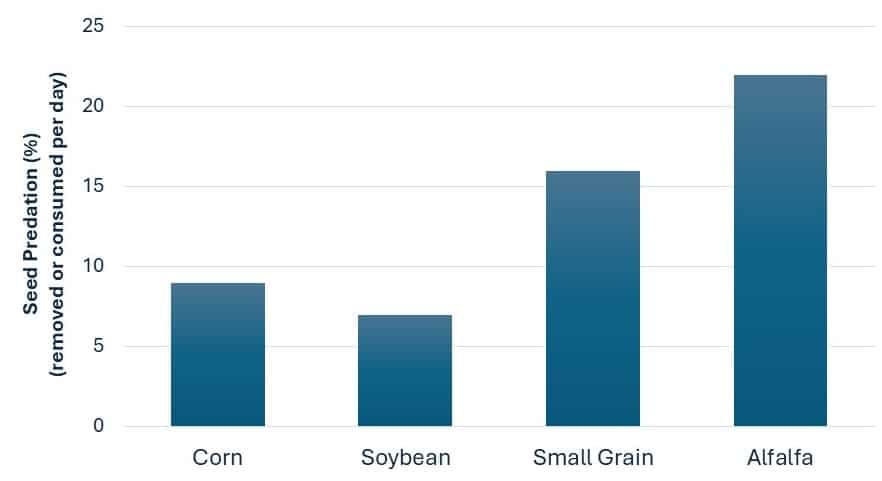

This type of biocontrol relies on understanding the biology and habitat suitability of beneficial insects or rodents that feed on weeds or weed seeds and could co-exist with production agriculture. Studies have shown some insects (especially ground beetles and crickets) and rodents (mice) will feed on weed seeds and potentially consume large numbers (Image 2). This requires suitable habitat and weed seed availability when these insects or rodents are present.

The amount of seeds consumed by these naturally occurring predators will vary depending on predator populations, weed seed availability, and field management. Crop management including rotation, tillage, residue cover, and pesticide use can all impact predator populations. Research in Iowa showed that when averaged over 12 sampling periods from May through November, seed losses ranged from 7 to 22% per day depending on the crop present in the field (Figure 2). The higher predation rates in small grain and alfalfa compared to corn and soybean may be due to differences in crop canopy development. Research conducted at Penn State showed that insecticide-containing seed treatments in corn and soybeans can reduce biocontrol predators. Thus, conserving habitat by using no-till practices, adding rotations of small grains and perennial hay cash crops, including cover crops, and reducing insecticide use are key management recommendations to encourage conservation biocontrol. In the end, conservation biocontrol may improve our ability to manage weeds using fewer herbicides.

4. Grazing

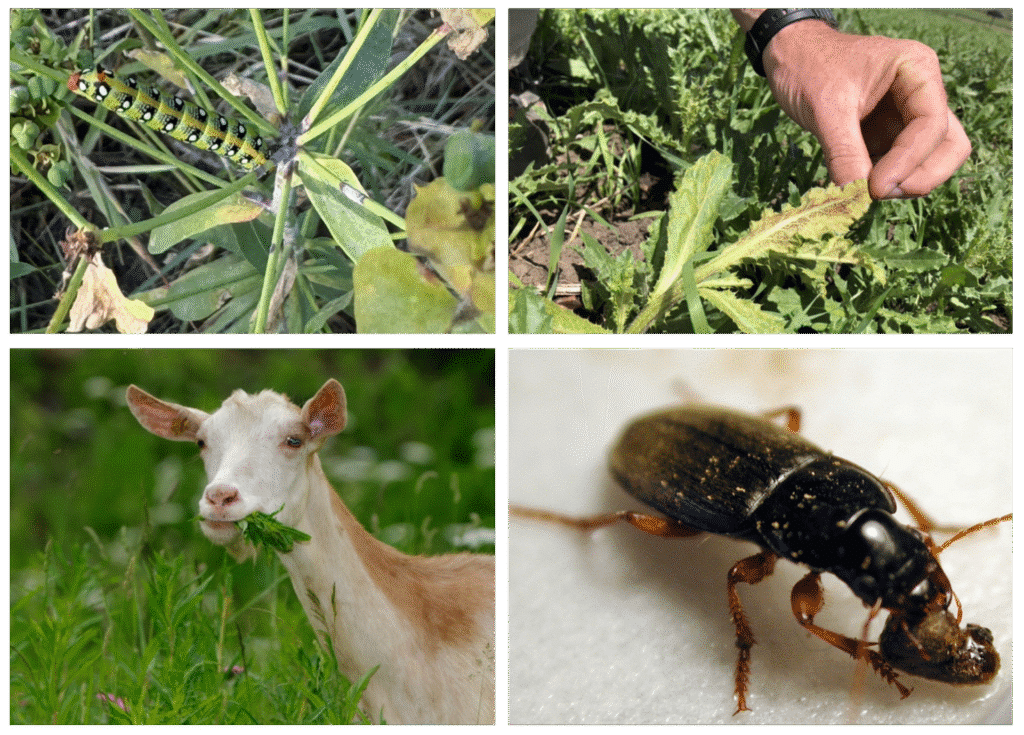

Livestock grazing is also a form of biological weed control and most livestock will forage on a variety of plants which can include some weeds. Although grazing will not typically eliminate an established infestation, with some direction and handling, they can minimize the spread and help suppress a number of potential problems. Some of the key management strategies using livestock and grazing to help manage weeds include:

Animal selection – The primary livestock in the US for grazing weeds are cattle, sheep, and goats. Other types of animals such as horses/mules, pigs, geese, and sometimes fish (e.g. grass carp) might also be considered in more limited circumstances.

Cattle are the most numerous type of livestock grazed in North America and can effectively reduce some grass and broadleaf weeds (Image 3). Cattle tend to be most effective at grazing young weedy grasses when they are most palatable. There has been some success in training cattle to eat certain weeds such as thistles and the knapweeds, which are less palatable. For more information, visit the OnPasture.com and other information written by Kathy Voth, retired BLM liaison, who has trained cattle to eat weeds.

Sheep prefer to graze on forbs (herbaceous broadleaves) and some grasses. They have been used to help control the knapweeds as well as leafy spurge. Effective control of leafy spurge with sheep can take several years and mature stands should be mowed before grazing early in the season. Leafy spurge can be poisonous to some livestock, and sheep should be monitored to avoid toxicity.

Goats are often considered the preferred animal for clearing brush and woody plants and will also graze some forbs. Some goat producers offer professional goat grazing services by leasing their herd to help manage invasive weedy plants. As examples, HireGoats.com and Goats On The Go have directories of operations throughout the US that lease goats for vegetation management.

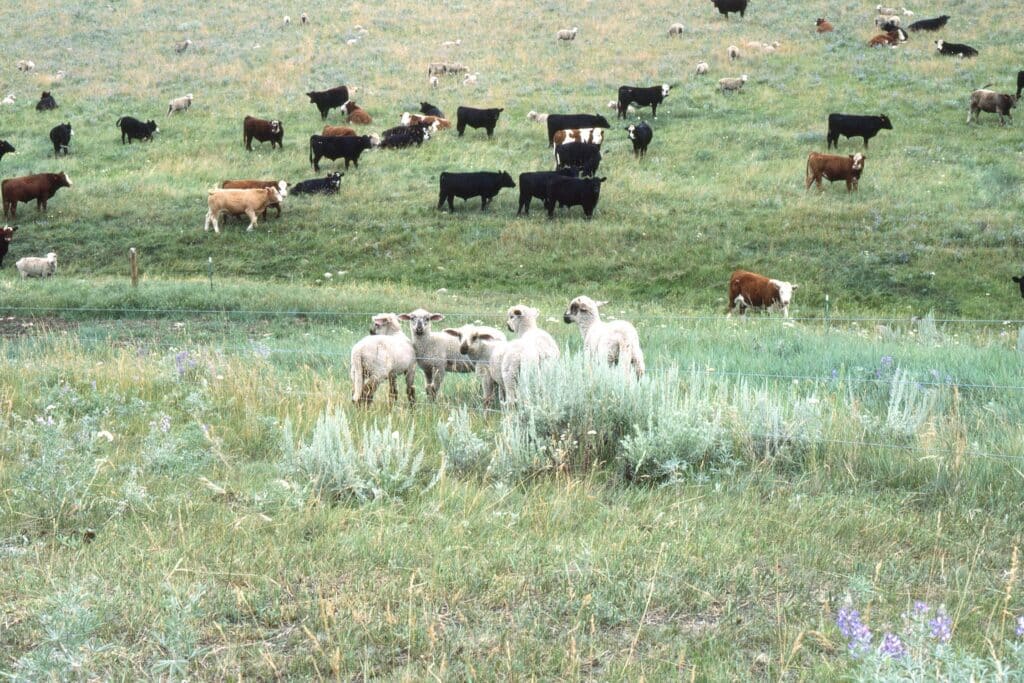

Multi-species grazing — mixing sheep and/or goats with cattle to increase the diversity of what the livestock can effectively eat is often beneficial for livestock producers to use (Image 4). Although this might improve weed management, the added labor and fencing, predator control, management of potential conflicts between mixed species, and the economics of the operation all must be considered.

Timing and intensity – The time to graze depends on what the animals will eat as well as the potential impact on the target species. In general, young weeds are most palatable, and grazing early will help set them back, reducing growth and the potential for weed competition and seed production. Grazing more mature plants can reduce flowering and seed production, but often mature plants are less attractive to grazing animals. Increasing stocking rates can help prevent selective grazing and make animals eat less palatable weeds (Popay and Field, 1996).

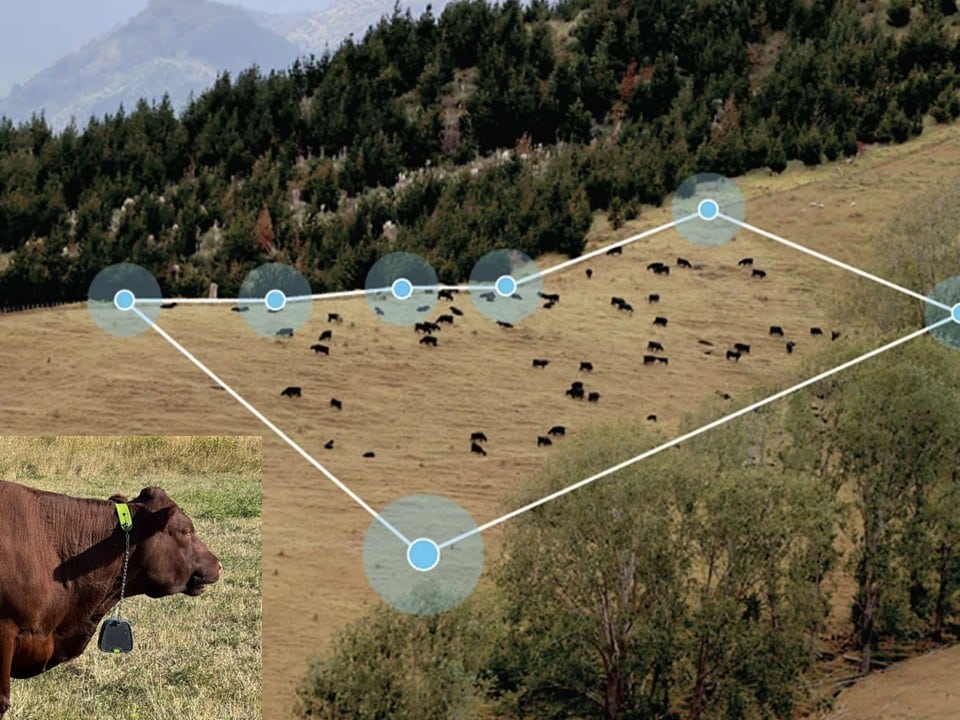

Confinement – Fencing is usually necessary as the greatest impact comes from intensive grazing for shorter periods of time. This typically requires moving electric fences to restrict animal movement. Concentrating livestock on weeds when those plants are most susceptible to damage can be important. New virtual fencing technology increases the potential to move and manage livestock quickly and easily and graze weed infested paddocks that were not previously managed (image 5).

Monitoring – The last ingredient is monitoring the effectiveness of grazing. That includes evaluating its effect on forage production, changes in weed species’ abundance, and potential weed seed production, as well as ultimately making necessary adjustments to the system. This may require qualitative and/or quantitative assessments such as before-and-after photos, or sampling paddocks and estimating weed and forage cover or yield. Reducing paddock size, adding animals, or changing the grazing timeline and intensity may be needed to fine-tune weed control.

5. Integrated weed management and biocontrol

Integrated weed management (IWM) involves combining two or more tactics to increase weed control success. Several biocontrol strategies are well suited for IWM. An obvious combination includes promoting better conservation biocontrol by reducing insecticide use, adopting no-till or minimum-till practices, and integrating cover crops to improve weed-seed predator habitat.

Take an example of classical biocontrol and IWM happening now in the West to explore management of Canada thistle (see Image 6). Researchers in Colorado and Utah, led by the Department of Biology at Utah State University, combined the use of Canada thistle rust (Puccinia suaveolens), an obligate biotrophic rust fungus, with mowing, tillage, and herbicide. Once established, the fungus alone decreased thistle density, but the combination with herbicides provided some of the best control. In another study looking at Canada thistle and the same fungus, the combination of a competitive crop sequence or rotation along with infection by the fungus reduced thistle biomass and competition more than exposure to the fungus alone.

Florida scientists conducted a review of experiments from 1987 to 2017 that integrated classical biological control with other management strategies such as herbicide, fire, mechanical control, grazing, and plant competition. They found that several experiments showed the benefits of combining biocontrol insects with other tactics, especially herbicides. However, the review also presented numerous challenges to consider when linking live organisms with these other tactics. Some herbicides and/or additives are toxic to beneficial insects, and they often eliminate an important food source (the target weed). Using prescribed burning or mechanical mowing can reduce favorable habitat and survival of biocontrol organisms. In some circumstances, biological control agents can be protected from these potential negative impacts by having untreated areas (refuges) or through use of temporal management (separating tactics over time).

On a positive note, several success stories come from combining livestock grazing with classical biological control to reduce the impact of invasive weedy plants. For example, research conducted in western North Dakota showed the integration of sheep and cattle grazing along with a biocontrol flea beetle (Aphthona spp.) reduced cover, stem density, and seed production of leafy spurge more than the insect alone. Research from Montana that integrated targeted grazing in July with sheep along with establishment of four biocontrol insects reduced the density of spotted knapweed by 86% and practically eliminated the production of viable seed over a four-year period. Additional research that investigates potential benefits of biocontrol in combination with other weed control tactics is needed to help land managers move the IWM adoption meter forward and reduce the impact of invasive weeds.

Author

William Curran, Penn State University

Editor

Emily Unglesbee, GROW

Reviewer

John Wallace, Penn State University

Citations and Resources

Bean, D, K Gladem, K Rosen, A Blake, R Clark, C Henderson, J Kaltenbach, J Price, E Smallwood, D Berner, S Young, R Schaeffer 2024, Scaling use of the rust fungus Puccinia punctiformis for biological control of Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop.): First report on a U.S. statewide effort,Biological Control,Volume 192,2024,105481,ISSN 1049-9644,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2024.105481.

Curran, W, M Ward, and M Ryan (2019) Biological Weed Control. Chapter 9, A Practical Integrated Weed Management Guide In Mid-Atlantic Grain Crops (https://growiwm.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/IWMguide.pdf).

CAB International or CABI (Home – CABI.org) – An inter-governmental not for profit organization that includes 48 member countries with the mission to improve people’s lives worldwide by providing information and expertise to solve agricultural and environmental problems. CABI has over 60 years’ experience of working on biological control of invasive weeds providing research and development of potential control agents.

Chichinsky D, C Larson, J Eberly, F Menalled and T Seipel (2023) Impact of Puccinia punctiformis on Cirsium arvense performance in a simulated crop sequence. Front. Agron. 5:1201600. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2023.1201600.

Colorado Department of Agriculture Palisade Insectary – https://ag.colorado.gov/conservation/biocontrol-at-palisade-insectary/current-research-and-methods.

Henderson, C, K, Gladem, S L Young, D W Bean, R N Schaeffer. 2025.

Integrated management of Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) in the Great Plains and Intermountain West using a biocontrol agent (Puccinia suaveolens)

bioRxiv 2025.03.19.644225; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.03.19.644225.

iBiocontrol (https://ibiocontrol.org/). Developed by the Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health at the University of Georgia.

Jacobs JS, Sheley RL, Borkowski JJ (2006a) Integrated management of leafy spurge-infested rangeland. Rangel Ecol Manag 59:475–482.

Lake, E.C., Minteer, C.R. A review of the integration of classical biological control with other techniques to manage invasive weeds in natural areas and rangelands. BioControl 63, 71–86 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-017-9853-5.

Liebman, M (2004) Managing weeds with insects and pathogens, 2004. Chap 8, In Ecological Management of Agricultural Weeds. Cambridge University Press, www.cambridge.org/0521560683.

Montana Biocontrol Coordination Project (https://mtbiocontrol.org) – A grassroots effort to provide leadership, coordination, and education to enable land managers to successfully incorporate biological weed control in their noxious weed management programs.

Mosley JC, RA Frost, BL Roeder, TK Mosley, G Marks (2016) Combined herbivory by targeted sheep grazing and biological control insects to suppress spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe). Invasive Plant Sci Manag 9:22–32.

North American Invasive Species Management Association (NAISMA) biocontrol resources. https://naisma.org/programs/biocontrol-resources/.

Popay I, and R Field (1996) Grazing animals as weed control agents. Weed Technol 10:217- 231. (https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.2003.00850.x).

Staver, CP (2004) Livestock grazing for weed management, 2004. Chap 9, In Ecological Management of Agricultural Weeds. Cambridge University Press, www.cambridge.org/0521560683.

Tooker, J.F., Douglas, M.R. and Krupke, C.H. (2017), Neonicotinoid Seed Treatments: Limitations and Compatibility with Integrated Pest Management. Agricultural & Environmental Letters, 2: ael2017.08.0026. https://doi.org/10.2134/ael2017.08.0026.

UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants – https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/.

Voth, K. Cows Eat Weeds (How to turn your cows into weed managers). 2010. http://www.livestockforlandscapes.com.

Westerman PR, Wes JS, Kroff MJ, Van Der Werf W (2003) Annual losses of weed seeds due to predation in organic cereal fields. J Ecol 40:824-836. (https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.2003.00850.x).