As your corn starts to canopy and close ranks this month, make sure those narrowing rows of today aren’t hiding the vines of tomorrow! The early season window to control corn-climbing weeds like burcucumber, bindweed, and morningglory is closing quickly.

“Get them while they’re small,” urges Penn State weed scientist Dwight Lingenfelter. Once the corn canopy and spray windows close up, farmers will have few options to manage vining weeds that creep through the field for the rest of the season, he warns.

Viny Villian Number 1: Burcucumber

Burcucumber, in particular, is a weed worthy of its own horror film series. This annual broadleaf weed is capable of producing 25-to-35-foot vines that snake between plants and across rows, crawling stealthily up corn plants through the summer. Once its tendrils breach the top of a plant, they set their sights horizontally, vining out across the canopy and wrapping up entire fields in a hellish spiderweb by harvest time.

“I’ve seen aerial shots of a whole field intertwined and wrapped together,” Lingenfelter says, with a touch of awe. “It’s a huge challenge to harvest, especially for silage fields. You have too much plant matter trying to go through the silage chopper, and it plugs things up and makes a mess.”

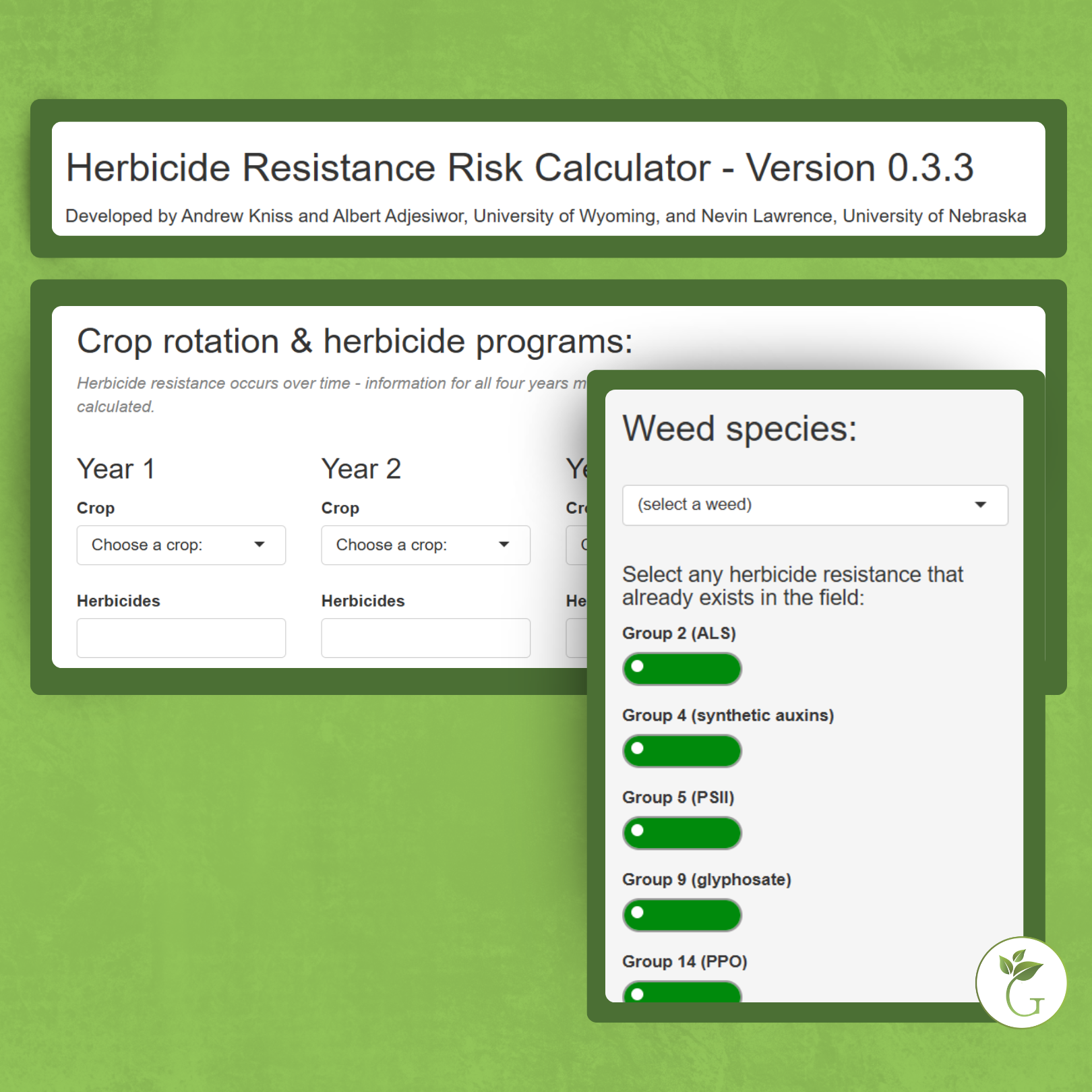

Fortunately for the industry, Lingenfelter and his PSU colleagues have been studying burcucumber control since the late 1990s – testing herbicide programs, tweaking timing and combinations and coming up with a solid recipe for early season control.

“The biggest thing is you need a two-pass program,” Lingenfelter explains. Start with a preemergence application containing a good residual herbicide and atrazine in the mix, such as Acuron, Lexar or TriVolt..

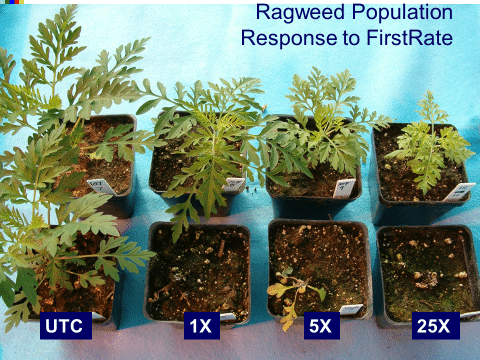

Then follow up with a robust postemergence pass. Peak (Group 2 – prosulfuron) remains one of the strongest and most consistent options against burcucumber, but its residual activity is so persistent that it comes with lengthy plantback restrictions that can sometimes derail a traditional rotation back to soybeans, Lingenfelter notes. One option is to drop your rate to a ¼ oz of Peak, and then add another herbicide premix, such as Halex GT or Acuron GT. And if you’re using a BOLT or STS soybean, which have varying levels of tolerance to Group 2 herbicides, you can bump that rate back up to a half ounce and still plant soybeans the following spring, he adds.

You’ll need every ounce of that residual. “Burcucumber continues to germinate all the way into August,” Lingenfelter warns. Even small plants can contribute to the seedbank, which makes an effective application within the canopy key. Drop nozzles can help get your postemergence herbicides down into the corn canopy at the ideal application timing, which is when corn is 24- to 30-inches tall. If you don’t have drop nozzles, making your post application at 12- to 15-inch corn heights will secure better coverage.

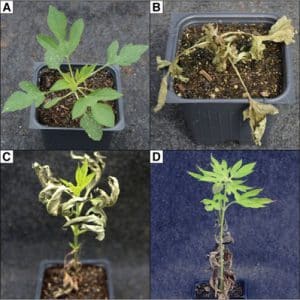

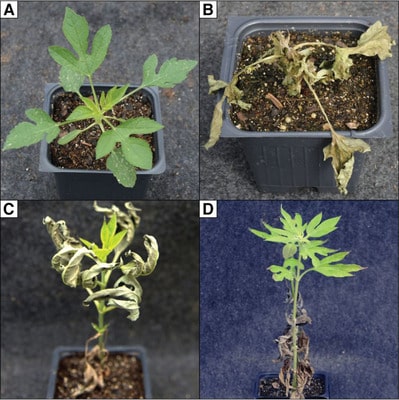

are still vulnerable to death by ensiling. (Photo credit: Dwight Lingenfelter, PSU)

And if you miss that window? The options aren’t great, Lingenfelter concedes. Don’t spray glyphosate on top of the canopy beyond the tassel stage, as some may be tempted to do, he warns. Not only is it illegal, but you won’t get very good control for your effort.

Instead, aim for early harvest, before vines can start their horizontal march across the canopy. “Consider using shorter season hybrids in fields where you know this will be a problem,” Lingenfelter suggests. This is where silage corn can come in handy, because if you can get in and chop silage before burcucumber seeds are fully mature (still cream to tan-colored, rather than dark brown or black), the ensiling process will kill them.

Although cover crops have not proven much protection against this troublesome weed (“It’s so large-seeded, it will blow through a 4-inch mulch,” as Lingenfelter puts it), no-till practices can help. “The dropped burcucumber seeds will remain on the surface and all germinate at the same time, and be exposed to your herbicide passes at the same time,” he explains. In contrast, tillage may simply distribute the seeds randomly throughout the soil profile, for uneven emergence.

Morningglory and Bindweed: Big Flowers, Big Problems

Although not quite as aggressive climbers as burcucumber, annual morningglory and bindweed are additional vining weeds that can wreak havoc in cornfields later in the season.

The morningglory species (tall, ivyleaf and pitted) are all annuals, spread by seed, so Lingenfelter recommends the same aggressive, two-pass program with residual activity, applied early in the season before corn – and the weeds – get too big. “You need atrazine in the mix, at least a quart and a half per acre, to get good control,” he says. “Products like Acuron and Lexar do a pretty good job in combination with additional atrazine.” And while glyphosate is notoriously weak on annual morningglory species when trying to control them in crop, dicamba-containing products and Liberty (glufosinate) can provide post activity, he adds.

In contrast, both hedge and field bindweed are perennial species, so they invest in powerful root systems in order to overwinter and return each year. That means preemergence and even postemergence herbicide applications won’t ever guarantee full control, Lingenfelter warns. Labeled rates of dicamba and 2,4-D, combined with glyphosate, may yield 80% to 85% control at best at postemergence timings.

Instead, target your primary assault on this weed in late summer and early fall, when the bindweed plants in your field are starting to hunker down and store up for the long winter. “With all the sugars going back down to the root system to fortify it for dormancy, the herbicide can more easily be taken down into the root system,” Lingenfelter explains. “With perennials, it’s all about killing the roots and rhizomes.”

Systemic herbicides like glyphosate, dicamba, and 2,4-D tend to provide the best control when applied during late summer/early fall. But be patient – “as with any perennial, it’s going to take multiple years to fully control it,” Lingenfelter notes.

See more on successfully managing bindweed in the fall here, from Kansas State University. For more details on managing morningglory in corn, see this publication from the University of Georgia.

Article by Emily Unglesbee, GROW; feature and header photos courtesy Dwight Lingenfelter, PSU