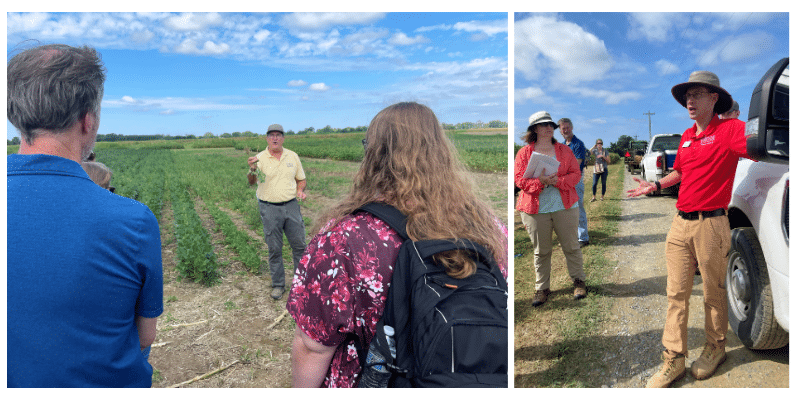

In its continuing quest to keep regulators connected with current farming practices, the Weed Science Society of America (WSSA), the University of Maryland and the University of Delaware led a group of EPA scientists through row crop and specialty crop research plots on September 13. The EPA staffers work on issues and topics across the United States and were eager to learn more about the agriculture industry in their backyards.

The field tour took place on the Wye Research and Education Center, which encompasses 1,000 acres along the Wye River on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Perched along the Chesapeake Bay, the center is well situated to evaluate conservation agriculture techniques, such as no-till, cover crops and field buffers, explained the Center’s director, Dr. Kathryne Everts.

Farmers in the mid-Atlantic states face some of the most restrictive regulations aimed at reducing nutrient run-off and pollution of the bay, University of Maryland Extension Agronomist Dr. Nicole Fiorellino reminded the tour. As a result, Maryland ranks number one in the country for the percent of agricultural fields in cover crops, and number two for fields devoted to no-till. “The mid-Atlantic region in general has led the way in the nation in conservation practices,” she explained.

This dynamic makes the University of Maryland’s agriculture research particularly essential, as lawmakers turn to the ag scientists there to help set those regulations. “For instance, UMD nutrient management recommendations have become their regulatory guidelines,” as Dr. Fiorellino put it.

Tillage, Cover Crops & Weeds

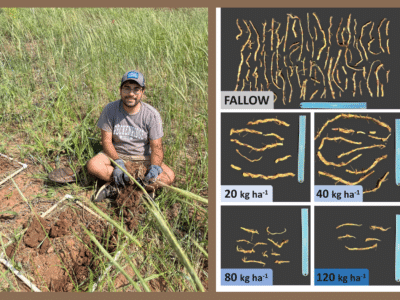

John Draper, a Centreville, Maryland farmer who works as the center’s farm manager, parked a series of tillage implements for the EPA employees to examine – a chisel plow, a cultipacker, and a field cultivator and roller. The equipment set the stage for a discussion of a nearby series of demonstration plots, examining the differences in corn stands grown on tilled plots, no-till plots and plots with cover crops.

Some of the agronomic differences observed between the plots were weed control, nitrogen uptake, stand uniformity and yield, Draper said. Draper and Dr. Fiorellino also discussed the differences in planting equipment and fuel consumption required for tilled versus no-till plots, complete with a planter demonstration.

There to help explain the effects of these different production practices on weed management – particularly the herbicide-resistant weeds plaguing the mid-Atlantic – were University of Delaware Extension Weed Scientist (and WSSA liaison and tour organizer) Dr. Mark VanGessel, as well as University of Maryland Extension Weed Scientist Dr. Kurt Vollmer.

Top of the list of problematic weeds in the region are Palmer amaranth, marestail (horseweed), lambsquarter, morningglory and johnsongrass. The group discussed the different herbicide-tolerant crop varieties available to help control these weeds, as well as the mounting herbicide-resistance problems that continue to endanger herbicide use in both the region and across the country.

Dr. Vollmer discussed recent research on how different nozzle tips affect the spray penetration of in-row (between individual crop plants) and inter-row weeds (between crop rows).

GROW postdoctoral researcher Dr. Eugene Law explained the role cereal rye cover crop mulch can play to help farmers implement different integrated weed management tactics. Cover crops help by smothering weed seeds early in the season and reducing and slowing their emergence, he explained. This can keep the weeds to a manageable size as farmers wait to get into the field to spray herbicides during the oft-soggy mid-Atlantic springs, Law said.

“Combining chemical and cultural management like this can help give you more flexibility with those narrow spray windows,” he said.

Draper also called attention to an equally wily pest of Maryland row crops – the booming local deer population. Bambi, it turns out, has a robust appetite for just about every row crop except sorghum and hemp. Draper estimated that many row crop operations lose $15,000 to $20,000 a year to deer feeding, particularly on the edges of fields. Solutions are costly and include repellent sprays, fencing, trap crops, and as a last resort, hunting.

Specialty Crops

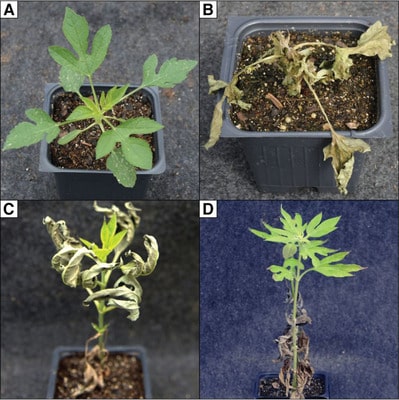

Chris Cochran, Talbot County vegetable farmer and Wye’s Fruit and Vegetable Farm Manager, walked the group through fruit production practices in the region. Highlighting grapes, blueberries, and blackberries, Cochran described the challenges of pesticide use on farms growing a variety of specialty crops. These crops have many of the same issues with herbicide resistance as field crops, and often without the diversity of tools available. Perennial crops do not allow for cultivation, there is a limited number of herbicides registered for these crops, and damage from herbicides can have ramifications for future years. For instance, perennial weeds such as poison ivy or green brier are not tolerated in “U-Pick” berry production and require chemical control, but use of glyphosate and accidental contact can kill the berry bushes.

Another complicating factor is the use of drip irrigation within the row of bushes, which keeps the soil moist and favors microbial activity that degrades herbicides faster than in non-irrigated field crops. This often leads to weeds emerging sooner in these treated rows and requiring additional management.

Cochran and his team also demonstrated specialized pesticide application equipment for specialty crops. They showcased a hooded sprayer, which allows for herbicides to be applied to the interrow areas of vegetables grown with black plastic, allowing for better crop safety and less herbicide use across the field. They also discussed the airblast sprayer and its utility for tree fruit.

Tour Impacts

Altogether, approximately 30 EPA staffers participated in the field day, representing at least five divisions within the Office of Pesticide Programs. In a poll taken after the tour, the vast majority (91%) reported that the experience had increased their understanding of agricultural production systems and the intersection of production practices and weed management.

“…[W]e learned a lot,” as one EPA participant put it. “I have an even higher appreciation for the enormous challenges farmers face, especially in the Mid-Atlantic.”

Catch up on last year’s WSSA-sponsored EPA field tour here.

Text and photos by Emily Unglesbee, GROW.