There’s a double threat looming for farmers using herbicides alone to manage weeds: regulation and resistance.

Both are undergoing significant changes that will force farmers to seriously rethink their weed management systems, Dr. Kevin Bradley, University of Missouri Extension weed specialist, told attendees of the National No-Till Conference in St. Louis, Missouri on January 12.

On the regulatory side, the EPA’s new commitment to creating pesticide labels fully compliant with the Endangered Species Act is underway and already altering herbicide labels and access.

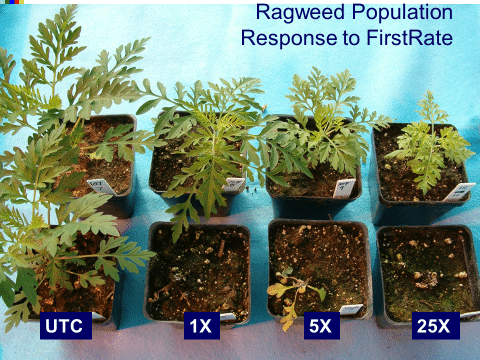

On the biological side, a newly recognized form of resistance – metabolic resistance – threatens to produce weeds able to tolerate herbicides they have never even encountered.

That’s the bad news.

On the bright side, Bradley and other presenters at the National No-Till Conference laid out a promising vision of the future of weed control, a busy and fast-developing world of cover crops, robotics, precision sprayers, drones, weed electrocution, harvest weed seed control and more.

“I think herbicides are still going to be a fundamental part of the way we do weed control, but I’ve seen us lose herbicides over and over and over to resistance,” Bradley explained. “It’s been pretty clear to most weed scientists that we’ve got to do something else other than just spray and spray and spray.”

Cover Crops & Planting Green

Several No-Till conference presenters stressed the growing body of research on the weed suppression benefits of cover crops and “planting green” – the practice of planting a cash crop like corn or soybeans into a green, live cover crop.

Jim Stute, an independent agronomist from East Troy, Wisconsin, was among them. Stute has used funding from the federal grant program, Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE), to set-up a series of field plots on planting green into soybeans. His goal? To see if planting green can help fight herbicide resistance.

So far, his results have demonstrated that when a cereal rye cover crop isn’t terminated until the anthesis stage in planting green plots, its increased biomass significantly increased the suppression of herbicide-resistant weeds – by 95% for marestail and 99% in waterhemp and giant ragweed. Even the “planting brown” plots – where the cover crops were terminated before planting, showed increased suppression rates of around 50% in all three weeds, compared to a traditional weed control program that relies on residual herbicides.

The only hiccup in Stute’s findings was that the planting green plots also reduced soybean yield, likely a byproduct of his northern U.S. location, where cover crops need up to 30-to-45 days of growth after soybean planting to produce enough biomass for weed suppression, Stute told GROW.

Overall, he concluded that cover crops and planting green can help farmers produce fewer weeds, which will require fewer herbicide applications, a key component in slowing the development of herbicide-resistance. His results echo those of many researchers, including Dr. Rodrigo Werle, a weed specialist at the University of Wisconsin, and GROW researchers and farmer-collaborators.

See more on planting green from the GROW Weed Management toolbox and from the GROW Resources page. See more research projects from Jim Stute here, including work on whether cover crops pay off for farmers.

Clockwise, from top left: Jim Stute presents his research at the 2023 National No-Till Conference. (Photo credit: Emily Unglesbee, GROW); A field of roller-crimped cereal rye boasts large biomass; Soybeans poke through a mat of cover crop residue; Planting green on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. (Photo credits: Claudio Rubione, GROW).

Weed Seed Destruction

Destroying weed seeds at or near-harvest was another commonly discussed option to fight herbicide resistance among No-Till attendees and presenters.

Bradley spoke of his research team’s work on weed electrocution, which he believes could be a way to manage late-season weed escapes – that is, as a “rescue treatment,” rather than a preventative method.

He also discussed seed impact mills, or weed seed destructors, namely the Seed Terminator. Like GROW researchers, Bradley and his Mizzou team have shown that these units can kill a majority of weed seeds by crushing them – but only those that actually enter the combine at harvest.

See more GROW research and news here on how seed impact mills like the Redekop SCU and integrated Harrington Seed Destructor work, as well as other harvest weed seed control options like chaff lining.

Perhaps the most futuristic harvest weed seed control practice featured at the No-Till Conference was the Weed Seed Destroyer, designed by Global Neighbor, an Ohio-based technology company.

The tube-like unit, designed to be installed on the back of a combine, sends a combination of blue light and heat coursing through the chaff and seeds that pass through it, a process known as “directed energy” or DE. “It leaves the seeds intact, but damages key cells within them,” explains Jon Jackson, president of Global Neighbor. The unit has been tested on chaff from wheat, rice and soybean fields.

The technology has been tested in the lab by several researchers at universities such as Central State University, Louisiana State University, and Texas A&M. So far, results are showing good weed seed kill rates ranging from 70% to 90%, according to LSU research.

But the unit is only now headed to the field for on-the-ground, harvest time testing, Jackson told GROW. There, his research team will work on tackling field realities such as crop and weed moisture, equipment clogs and more.

Watch the GROW newspage for more research and news to come on the Weed Seed Destroyer.

Clockwise, from top left: Jon Jackson presented the mechanics of the Weed Seed Destroyer at the 2023 National No-Till Conference. (Photo credit: Emily Unglesbee, GROW); Virginia Tech researchers collect chaff from a combine to determine where weed seeds go during harvest (Photo credit: Claudio Rubione, GROW); Virginia farmer Kenton Moyer displays his integrated Harrington Seed Destructor. (Photo credit: Emily Unglesbee, GROW); A chaff line, where weed seeds will be concentrated the following season. (Photo credit: Michael Flessner, Virginia Tech); The Weed Zapper at work in the University of Missouri’s test plots. (Photo credit: Mizzou Weed Science Team).

Article by Emily Unglesbee, GROW