Sometimes when a plan looks good on paper, it doesn’t necessarily mean its execution is the best idea.

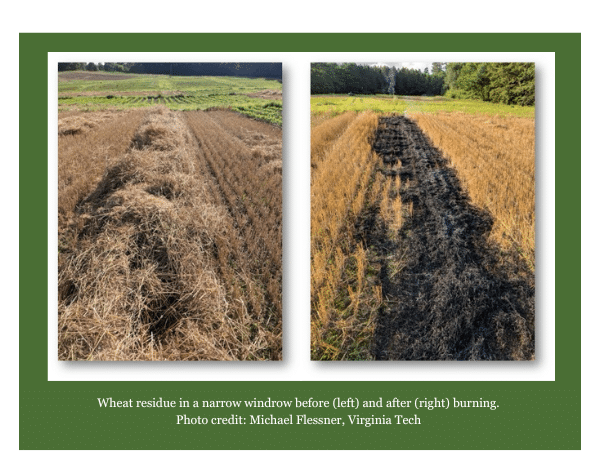

Weed scientists are always searching for the most effective ways to reduce herbicide-resistant weeds in crop fields. Australian farmers have been using narrow windrow burning effectively for some time to reduce weed seeds. But this technique comes with some shortcomings that farmers and agronomists should think about before getting out their lighters.

“Narrow windrow burning is definitely a way to control some weed seeds,” says Dr. Michael Flessner, a weed scientist at Virginia Tech. “We’ve studied this technique for three crop seasons and found it can be successful.”

Narrow windrow burning (NWB) is a form of harvest weed seed control that literally burns rows of crop residue. Weeds that have escaped from herbicide control are chewed up by the combine and deposited in rows along with the crop residue. Many weed seeds survive the ride through the combine to flourish the following spring. NWB is an extra step to kill the bulk of those weed seeds.

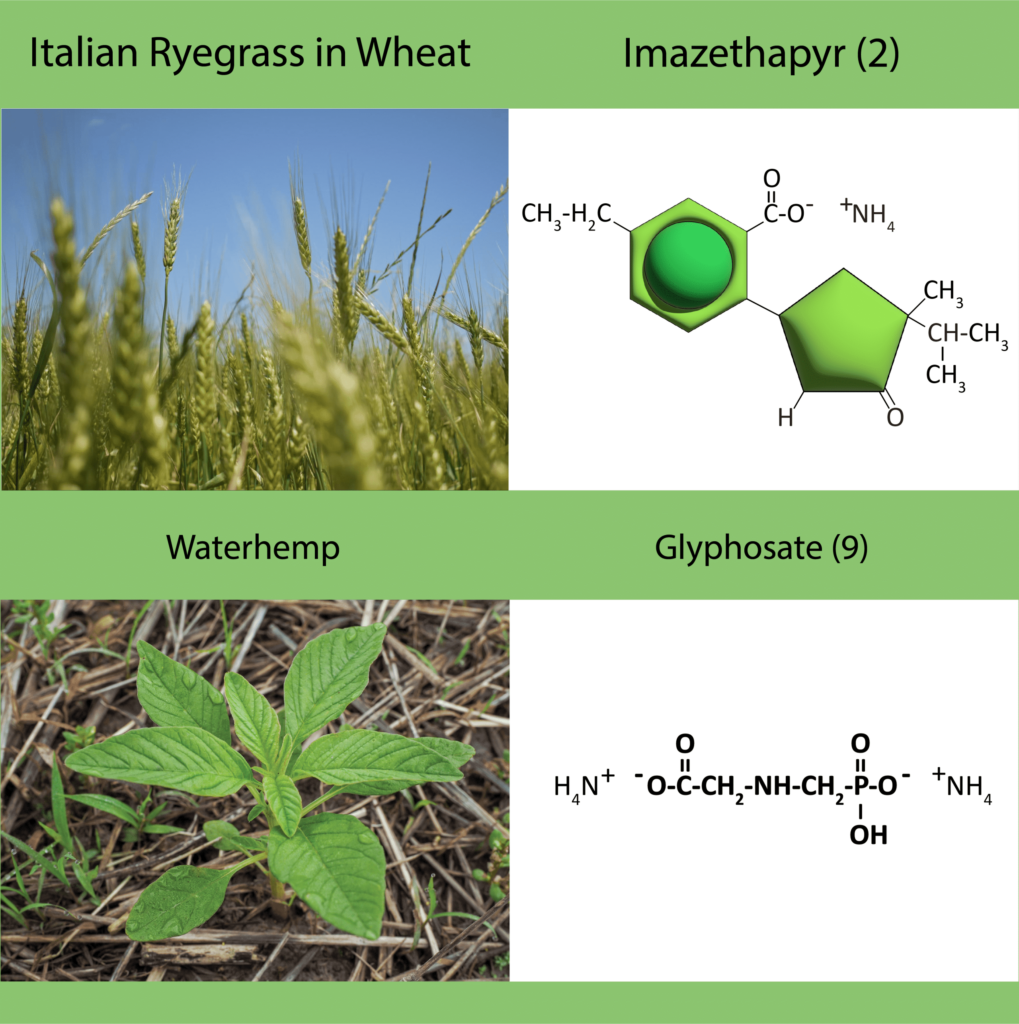

Flessner’s team’s research demonstrated nearly an 80% seed kill rate of Italian ryegrass following a wheat harvest and an 86% seed kill rate of Palmer amaranth after soybeans. His team’s research supports a study published in 2020, led by University of Arkansas weed scientist Dr. Jason Norsworthy.

Norsworthy’s research measured the heat index, or how hot the fire needed to be to kill the weed seeds. The experiment was conducted in a kiln to measure the temperature and time needed to kill the weed seeds. They also conducted this with windrows in the field over two seasons. The study focused on seeds from Palmer amaranth, barnyardgrass, johnsongrass and pitted morningglory. Regardless of the heat index achieved, all the seeds were killed with NWB.

The research conducted by these two teams demonstrates that NWB can be a viable technique — but only when conditions are perfect for burning.

Playing With Fire Can Be Risky

The risk of fire escape is an obvious drawback to NWB, and Flessner experienced this at one of their research locations.

“One major drawback with NWB is that the fire can get out of hand,” he says. “We had a scary incident that revealed to us the dangers with this technique.”

The Virginia Tech team worked with a farmer who was willing to try NWB, but only with part of the field. When they set fire to the first windrow, it behaved as it should. But as the wind picked up, the fire jumped from one windrow to the next.

“Once the fire jumped to the part of the field that was conventionally harvested, there was really no stopping it,” Flessner says. “Thankfully, once the fire got to the road, it stopped. It was certainly terrifying, and we were lucky that it ended with no injuries and no loss of equipment or crops.”

Soil Health, Time Pressures & Other “Red Flags”

In addition to the risk of fire getting out of hand, there are other concerns with NWB, especially for soil-conscious farmers.

“Crop residue burning results in a loss of organic matter going back into the soil, reducing fertility,” Flessner says. “Also, burning off the residue exposes the soil, making it vulnerable to erosion. In soils that have low organic matter, losing the residue doesn’t help to improve or maintain soil fertility.”

In regions that use double-cropping, time is an issue and NWB may be difficult to work into the system, Flessner says, as conditions need to be just right for burning.

“When farmers double-crop soybeans after wheat, the soybeans need to be planted as soon as the wheat is harvested. Every day that goes by, they lose soybean yield potential,” he says. “There’s no time to wait for good burning conditions and forcing it could lead to mistakes and burning in poor conditions.”

Narrow windrow burning is forbidden for those who reside in areas where it is outright illegal to burn or when the National Weather Service issues Red Flag warnings. Additionally, NWB results in an uneven distribution of carbon with the remaining ashes. If the ashes haven’t blown away, the carbon that goes into the soil may increase fertility only along the windrows, creating bands of soil with higher fertility. This may result in uneven crop yields.

Narrow windrow burning has shown it can be effective in killing weed seeds in the field. But farmers need to consider the pros and cons carefully and consult with their crop agronomist before taking measures into their own hands.

Article by Carol Brown; header and feature photo by Claudio Rubione, GROW