Short corn may not stand tall, but it does stand strong, thanks to its shorter internodes and decreased lodging risks. But where does that leave weed control? That’s exactly what an array of researchers across the Cornbelt are investigating, as these shorter corn hybrids, which stand only about 7 feet tall, start to become commercially available to U.S. farmers from a handful of major seed companies.

Early research from Michigan State and Penn State suggests that short corn can improve weed control and yields, but results vary across regions and production systems. In silage corn systems, short corn can be grown in narrow rows and at a higher density to manage weeds and improve yields, Penn State Ph.D. student Noelle Connors reports. Simultaneously, findings from Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania suggest that while high-density planting leads to improved yields, weed control is more dependent on herbicide programs than corn variety, says Dr. Erin Burns of Michigan State University.

Weed Control and Improved Yield

Planting short corn at a high seeding rate (48,000 seeds per acre) and in narrow rows (15 inches apart) can have a significant impact on broadleaf weeds that emerge four-to-five weeks after corn planting. Connors’ first year results demonstrated these planting conditions resulted in a 90% reduction in weed seed production compared to standard corn planting. She also saw a 15% increase in short corn yield when planted in narrow rows.

“Corn is known to be a competitive crop, but when you take some of that competitive ability away by shrinking it, how does that affect our weed management systems?”

Nick Basinger, University of Georgia

“We’ve only completed one year of research so far, but we have found that short corn reaches similar yields to silage corn, although it needs to be planted in narrow rows and high populations,” Connors explains. “We also found that high planting density and narrow rows suppressed weed biomass and seed production.”

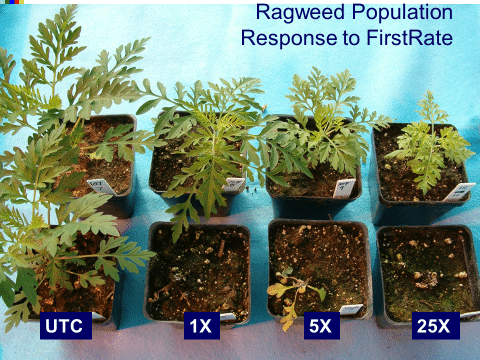

At Michigan State, Burns’ research comparing weed management between normal-height corn and short corn saw that using a two-pass system (preemergence followed by postemergence herbicide application) in both corn varieties resulted in weed control 3% to 8% greater than just using a preemergence or early-post emergence program. But 90% weed control was achieved by using any of these herbicide programs. “We did find some slight differences, but weed control was still greater than 90% overall,” Burns notes. “And we didn’t notice any herbicide injury on the corn, or implications on yield.”

Burns also examined how two different short corn leaf shapes—pendulum (floppy) and upright (stiff)—affect rate of canopy closure, but ultimately found no difference in that rate.

Burns did find that planting either short corn variety at a high density (40,000 seeds per acre) resulted in a greater yield than using the standard 32,000 seeds per acre.

“I think the take-home message is that [short corn varieties] are very similar to our traditional corn hybrids, but we have the ability to increase planting populations which benefits yield…and will have long-term impacts on the weed seedbank.” Burns states.

But the success could come with some economic tradeoffs, Connors warns. Planting short corn in higher densities and narrower rows means more money is spent on corn seed. “We’re working to better understand the economic tradeoffs of higher seed costs or different equipment requirements.” Connors says. Both Connors and Burns plan to repeat their study this 2025 field season to gather more data.

What We Don’t Yet Know

With some short corn varieties targeted to specific regions of the U.S., Connors’ weed management implications primarily cater to the northeastern United States. “We’re in silage corn, where many farmers already grow corn in narrow rows, so it’s most relevant in this system,” Connors explains. “But I think that the weed suppression benefits of short corn do have potential nationwide.”

Between the different varieties and this corn system’s recent commercialization, researchers like Dr. Nick Basinger at the University of Georgia emphasize that many questions remain concerning how short corn varieties might affect weed management in fields. “Corn is known to be a competitive crop, but when you take some of that competitive ability away by shrinking it, how does that affect our weed management systems?” Basinger wonders.

In 2024, Basinger began collecting data on short corn’s critical period of weed control. He seeks to understand if there are any differences between short corn’s critical period of weed control and normal-height corn varieties, a factor that hasn’t been examined in previous research and could alter how farmers manage weeds in short corn fields.

Basinger’s research is supported by the Georgia Corn Commission, who are curious to know if this corn system is adaptable to the area by using 30- to 36-inch row spacing that is more in line with what farmers in Georgia are using. He will be repeating his experiment this year.

Questions also remain about herbicide use and management, seeding rates, fertility, water requirements, and the agronomics of short corn, Basinger says.

With the promise that short corn holds for weed management and improving yields, all eyes are looking a bit lower to see what researchers find.

Visit GROW’s website for more information on cultural weed management strategies such as row spacing.

Article by Amy Sullivan, GROW; Header and feature photo by Noelle Connors, Penn State.