Listen to this article above!

Could those creepy crawlies underneath the soil actually be helping farmers battle weeds?

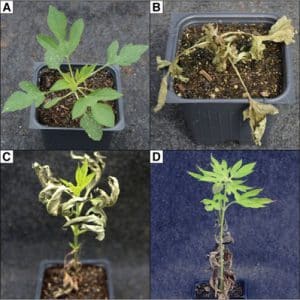

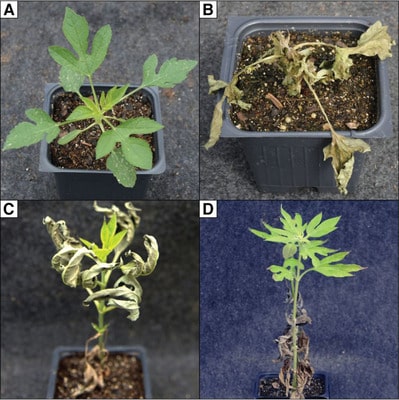

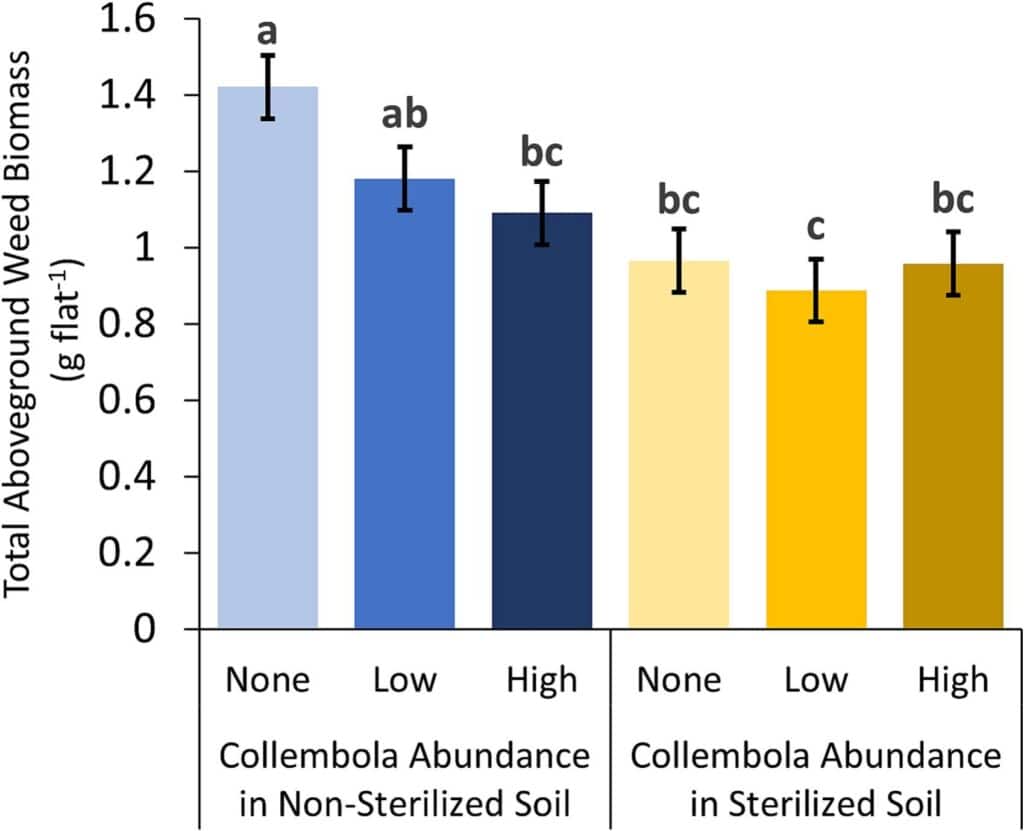

New research suggests that soil microarthropods, specifically the springtail species Isotomiella minor, can decrease weed biomass by up to 23%, according to Virginia Tech’s Dr. Ashley Jernigan. That effect did follow increased weed emergence in the first two weeks of treatment, before emergence decreased in the last two weeks of the trial, potentially due to differences in weed seed coats. While the findings are promising, a combination of unexamined soil-biological factors could be influencing the results, Jernigan and co-author Dr. Lynn Sosnoskie caution.

Although this study focused on Isotomiella minor, a springtail species that resemble wriggling grains of white rice, there are as many as 6,500 other species of springtails in soils around the world. “It’s a really ubiquitous species that’s commonly found, and it’s a good model organism when talking about the effects of Collembola,” Jernigan explains.

A Below-Ground Buffet?

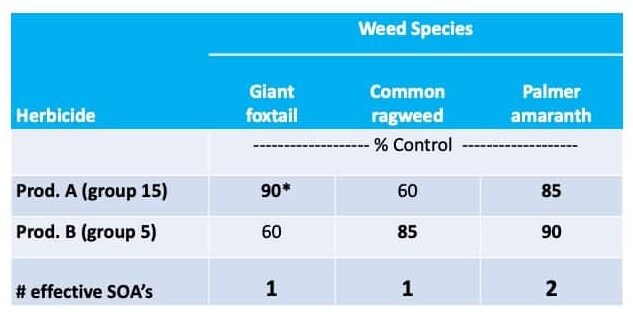

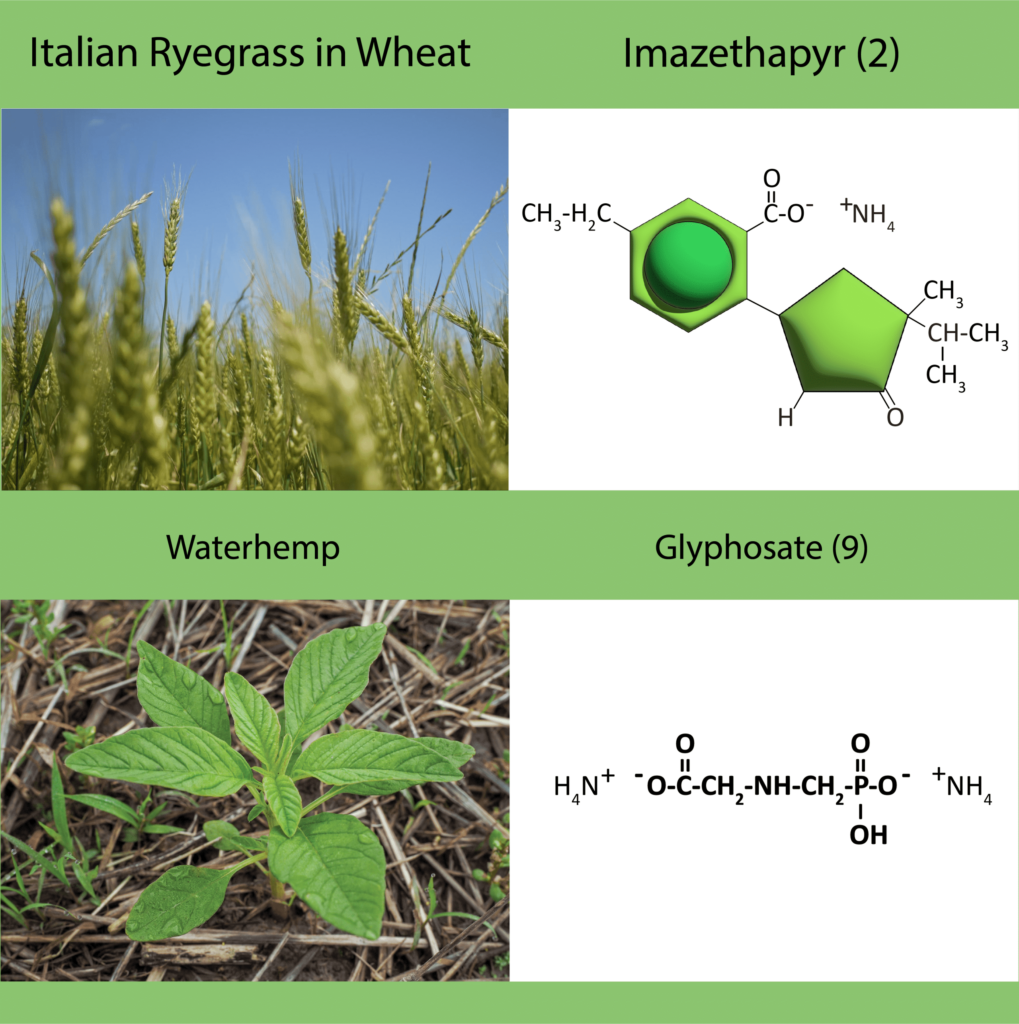

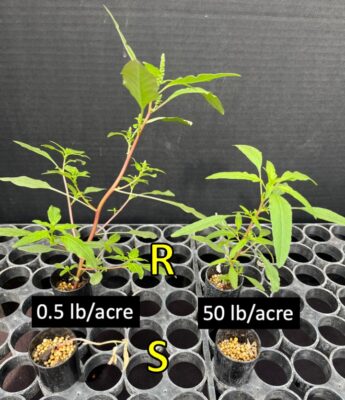

The authors found that over the four-week greenhouse trial, yellow foxtail, Powell amaranth, and waterhemp emergence decreased by 41%, 67%, and 43% respectively. This is despite waterhemp and Powell amaranth weed emergence increasing in the first two weeks of the trials, before decreasing.

Pigweeds seemed particularly susceptible to these tiny helpers. Powell amaranth and waterhemp saw a 55% and 32% reduction in biomass, respectively. As I. minor population increased with treatments (zero, 100, and 200 springtails per 4.37 liter plastic container), so did weed biomass reduction. This effect was most noticeable in the non-sterilized soil samples, which suggests that the springtails are not the only factor contributing to weed suppression.

Weed germination decreased by 11% on average when researchers applied fertilizer (Kreher’s Poultry Litter Compost 5–4-3 OMRI) to the springtail study cups. The fertilizer application did not impact the springtails.

Take Off Your Seed Coat

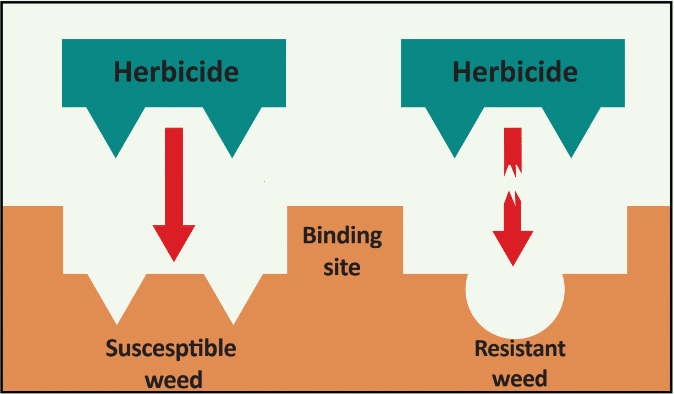

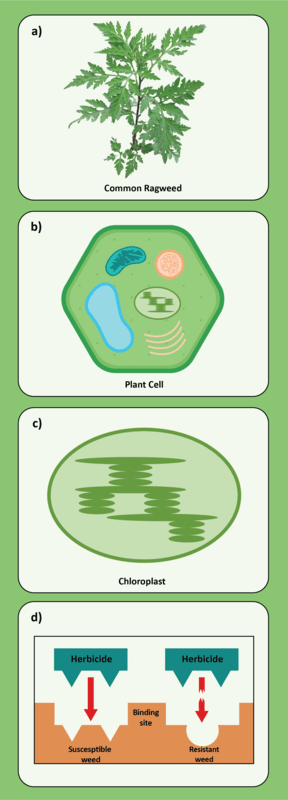

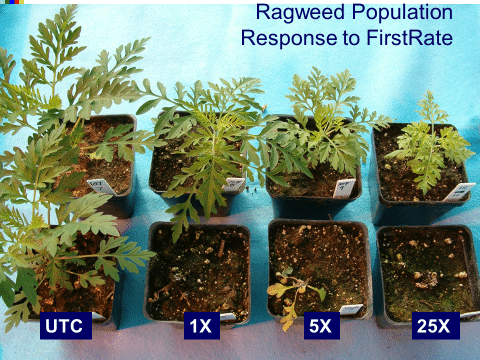

Why did the springtails seem to sometimes positively affect weed germination? It may be due to the weed’s seed coat, Jernigan says.

Weed seeds with a thick and textured seed coat could be fed on by springtails without affecting the seed’s viability. This could explain why certain weeds such as yellow foxtail and common lambsquarters were less affected than weeds with thinner, smoother seed coats such as pigweeds.

Similarly, Jernigan thinks that thinner seed coats might have contributed to some weeds’ initial increase in germination. “Whenever there was a thinner seed coat, the Collembola feeding would potentially initially stimulate germination, but then harm the seed by likely feeding through to the embryo,” Jernigan explains.

It’s also possible that the springtails aided weed emergence by increasing nutrients in the soil, rather than feeding on the weed seed coat, Jernigan adds.

Give It Up for I. Minor…and Others!

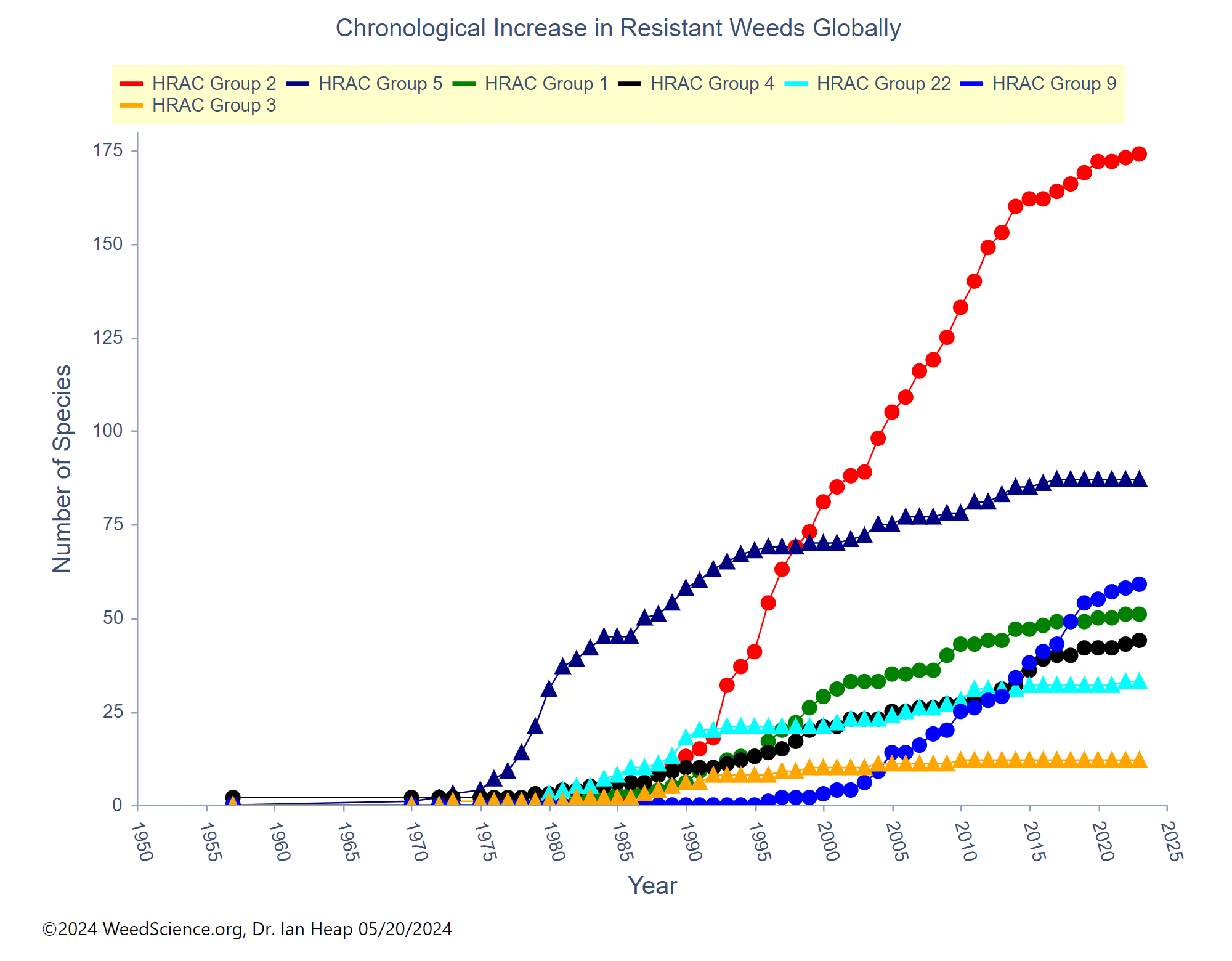

Jernigan’s current research conclusion is clear: The springtails showed potential as a weed management tool, but they most likely weren’t responsible for all of the observed effects on weed biomass and germination, and many questions remain unanswered.

Previous research has already found that the soil-biological community is tight-knit and highly dependent on each other. There could be a whole host of variables adding to the effect that I. minor created, including: weed seed coat, nutrient availability, crop and weed species, springtail feeding preferences, and other soil microarthropod species. Different combinations of these variables could cause different springtail behaviors, creating different results than what researchers saw in this study.

Yet Jernigan’s research is a critical first step to understanding the role of the soil’s biological community in fighting weeds and protecting crops. “Identifying and understanding these interactions in the greenhouse/lab is needed before additional research can be done in the field,” says Dr. Mark VanGessel, a weed scientist and Extension specialist at the University of Delaware.

Jernigan’s research on this topic is ongoing. She hopes to single out what role each variable plays, as well as examine weed biomass in soil with multiple species of microarthropods. “It’s vital that we start to describe the soil environment that our crops and weeds are growing and persisting in,” says Dr. Lynn Sosnoskie.

In the meantime, Jernigan suggests that farmers could alter their field management plans to account for microarthropods in the soil by following the four principles for managing soil health from USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

Explore GROW’s website to learn more about biological weed control and other weed management tools.

Article by Amy Sullivan, GROW; Header and feature photo by Ashley Jernigan, Virginia Tech.