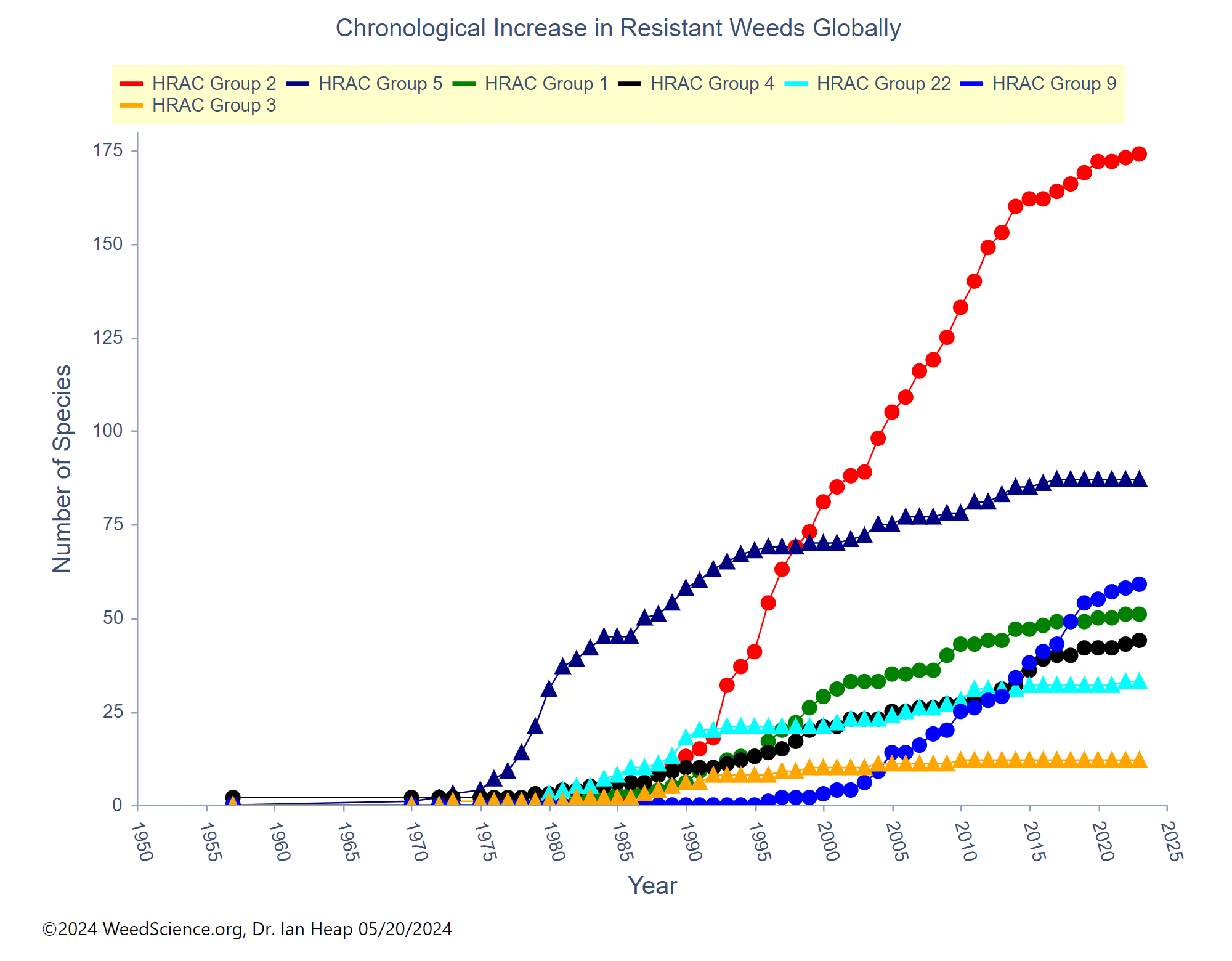

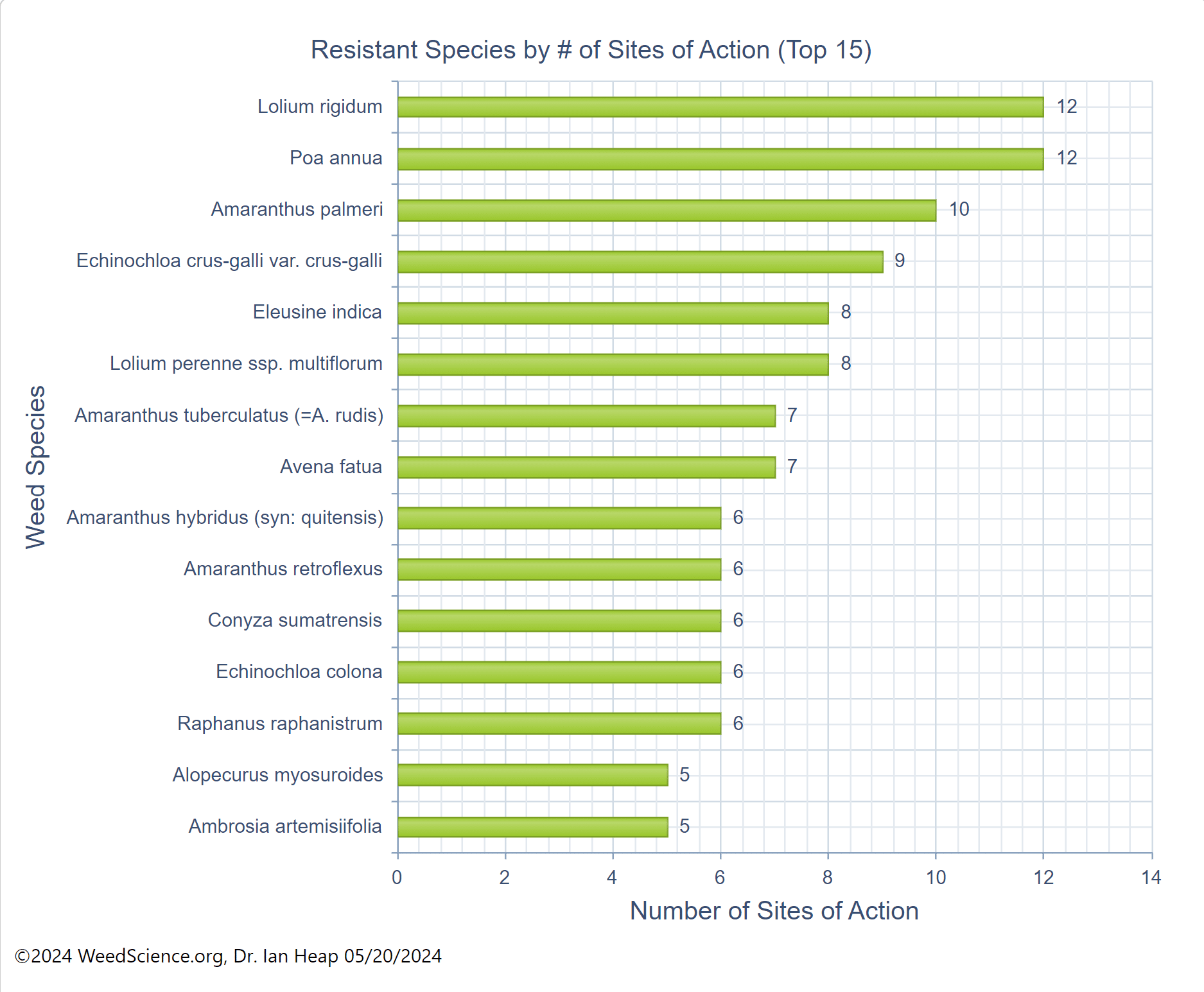

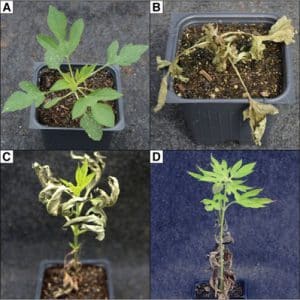

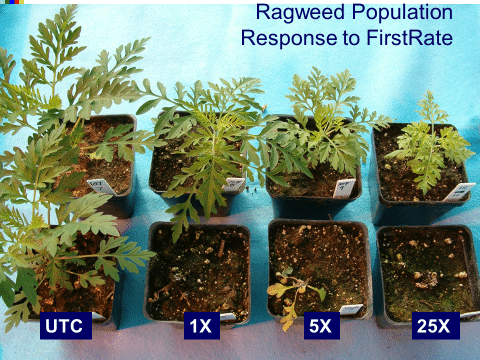

Invasive kochia has become a common enemy on farms in the western half of the U.S. Its herbicide resistance, coupled with its ability to germinate in early spring, survive extreme temperatures, and endure drought and salinity, has made it a pesky weed to eliminate.

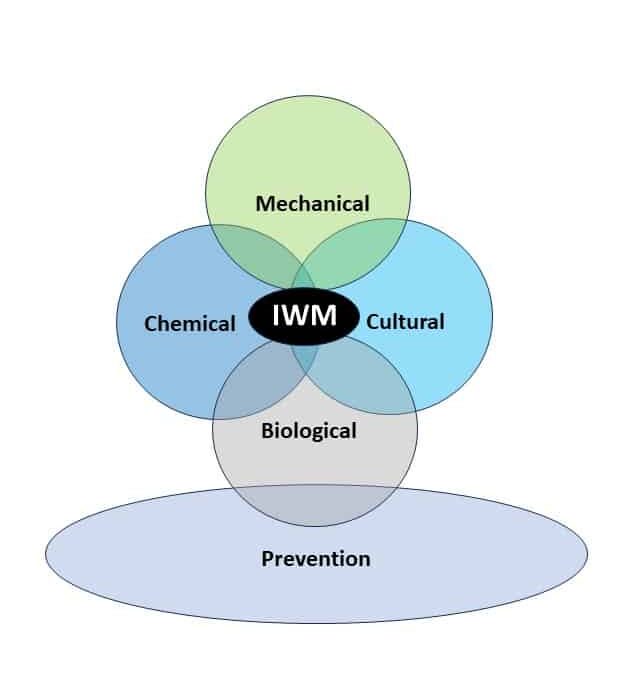

In their recent study, Ph.D. student Sachin Danda (Kansas State) and Dr. Vipan Kumar (Cornell University, formerly Kansas State) examined how cover crops and residual herbicides affect kochia’s emergence and seedbank. Their findings indicate that, when combined with residual herbicides, fall- or spring-planted cover crops can reduce around 90% of glyphosate-resistant kochia emergence in a field.

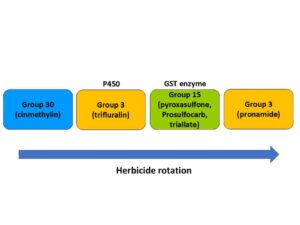

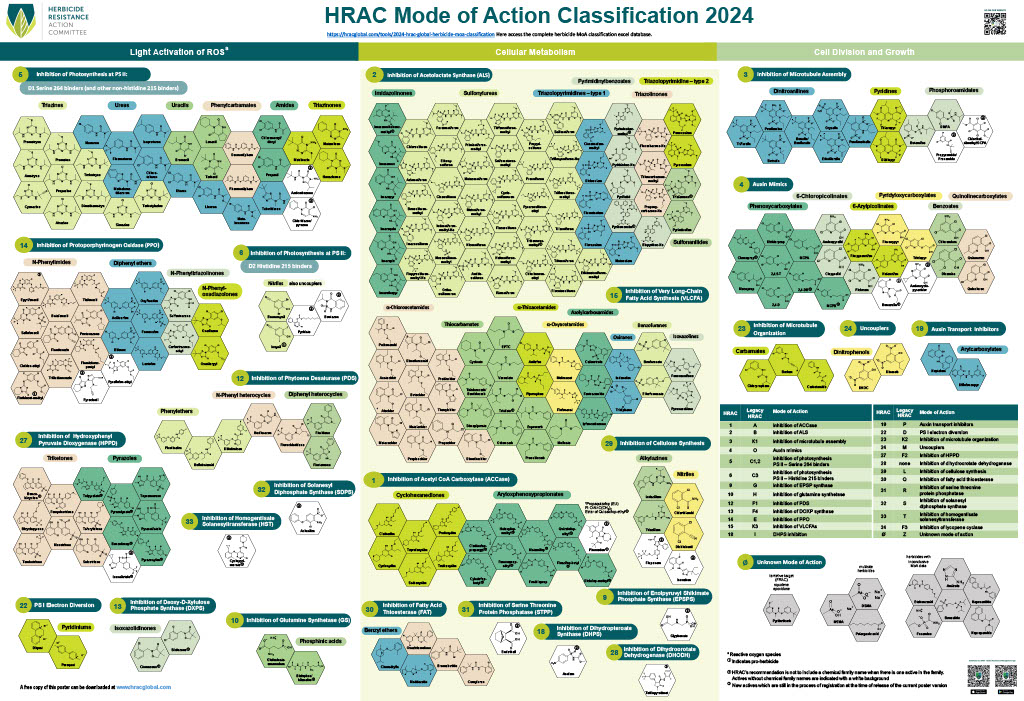

For their study, two field experiments were conducted during 2021-22 and 2022-23 growing seasons at the Kansas State Agricultural Research Center in the Central Great Plains region. These fields were in a rotation of winter wheat, grain sorghum, and fallow, and had a kochia weed seedbank. The residual herbicides used were acetochlor/atrazine (fall-planted cover crops) and flumioxazin/pyroxasulfone (spring-planted cover crops).

Cover Crops

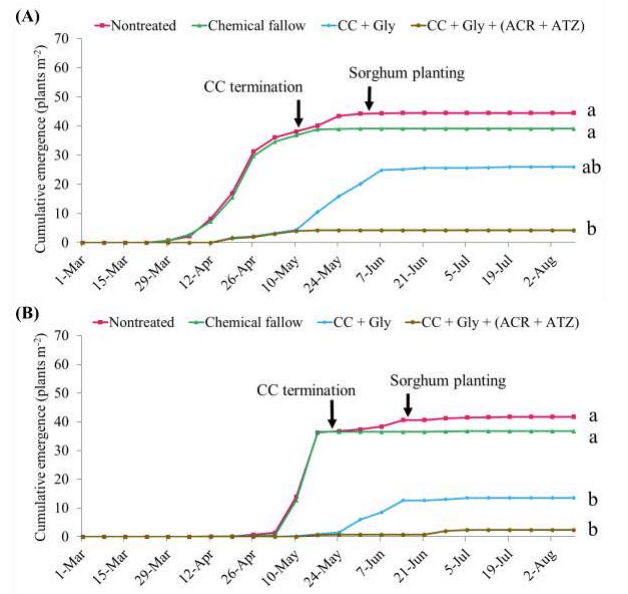

The fall-planted cover crop mixture included winter triticale (60%), winter peas (30%), radish (5%), and rapeseed (5%). This mixture, when used with glyphosate plus acetochlor/atrazine application, created a combined effect that led to no peak emergence in glyphosate-resistant kochia, and ultimately suppressed 90% to 95% of kochia emergence.

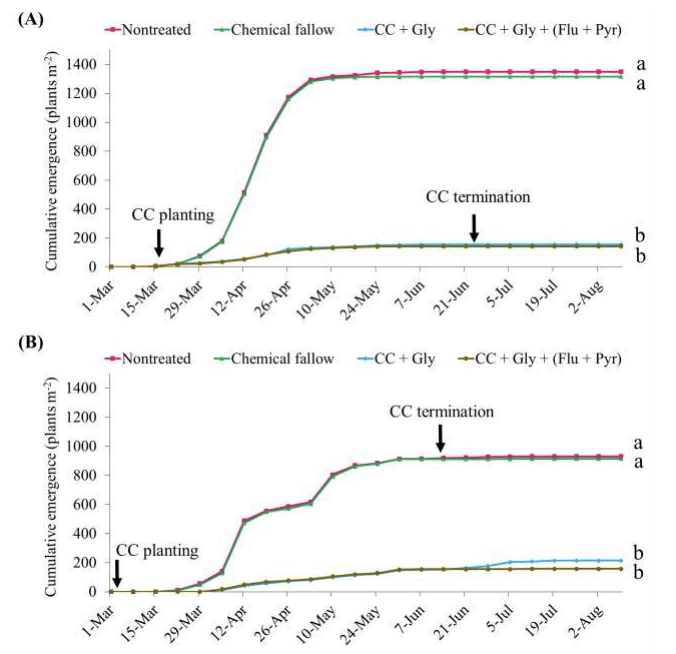

The spring-planted cover crop mixture included oats (40%), barley (40%), and spring peas (20%). This cover crop mixture led to suppressed emergence of 83% to 90% of kochia in a field.

The fall-planted cover crop mixture was shown to suppress kochia emergence for up to five weeks, while the spring-planted cover crop mixture suppressed emergence for up to two weeks.

Notably, neither seasonal mixture contained cereal rye, one of the most common cover crops. “If you look at cover crops in the U.S. cereal rye is the dominant species,” Dr. Kumar notes, “But we are in wheat country in that region, and rye is bad for wheat producers. Rye seed in wheat grain can cause issues in dockage and the grain quality.”

The cover crop species in this experiment work to create a large biomass like cereal rye, while also providing plant diversity and the potential for livestock grazing.

Rainfall in the Central Great Plains

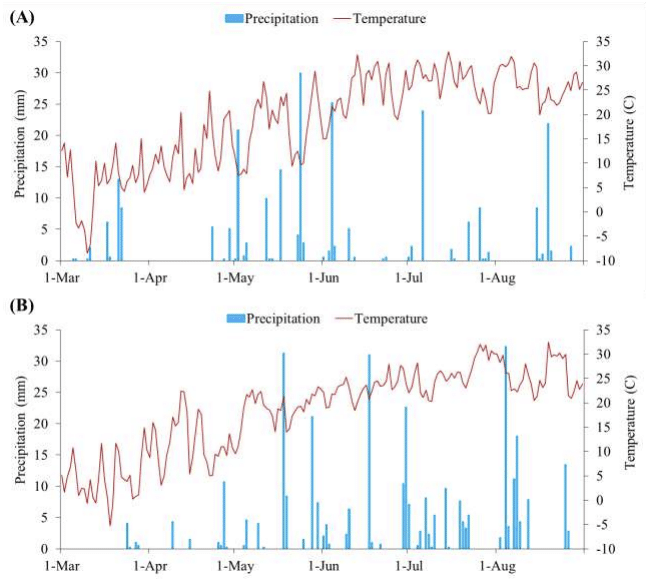

The Central Great Plains region is not known for consistent rainfall, a factor that can affect both cover and cash crops, and was observed in this study.

Dr. Kumar notes that the semi-arid climate of the Great Plains resulted in the sorghum planted in 2022 only reaching a fraction of its anticipated height. “A usually 6-foot plant only grew to 2- or 3-feet and produced a little head on top,” he notes. “Those plants were quite stressed out.”

Additionally, research increasingly agrees that a cover crop needs a biomass of over 5,300 pounds per acre to be considered effective at suppressing weeds. Dr. Kumar shares that this figure is challenging for many Great Plains farmers in semi-arid climates to attain. “It is hard to achieve 6,000 kilograms of cover crop biomass in a semiarid environment of High Plains with limited rainfall and high summer temperatures,” Kumar says. But despite neither cover crop mixture reaching 5,300 pounds per acre of biomass, they still proved effective at suppressing kochia when paired with residual herbicides.

But Dr. Kumar also notes that, “every year is a different year,” and that ongoing research is tackling how to provide more accurate seasonal weather conditions to help reduce the loss of crops in coming years, ensuring that both cover crops and cash crops can be planted with more certainty of their survival in semi-arid regions like western Kansas.

Kochia Escape

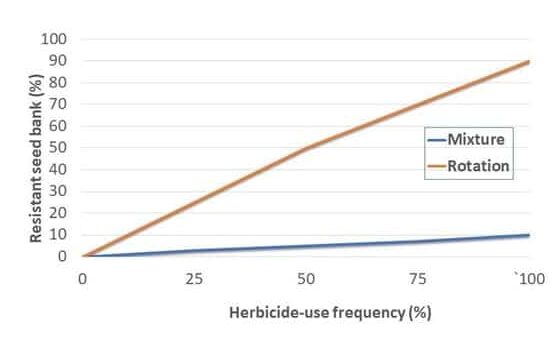

While both fall- and spring-planted cover crops (in tandem with residual herbicides) showed 90% effectiveness in reducing germination, the remaining 10% of escaped kochia contributes to the weed’s seedbank.

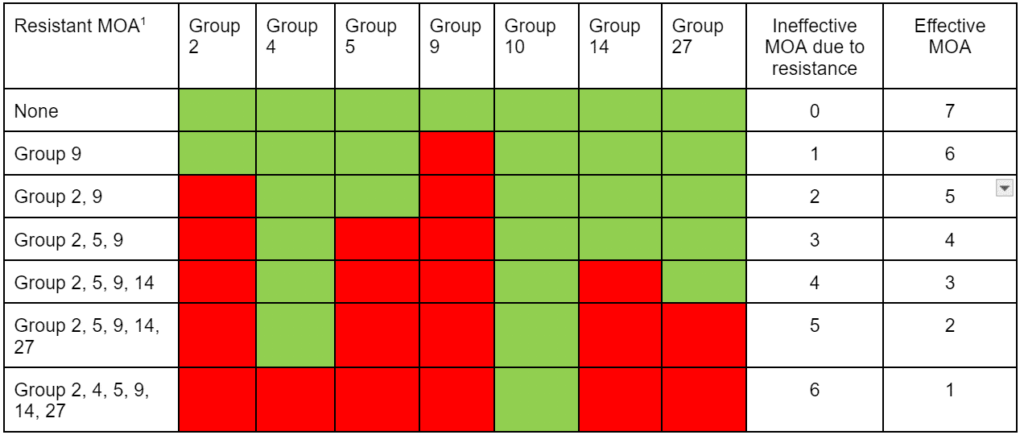

Kumar theorizes that harvest weed seed control methods like chaff lining or seed impact mills could help reduce the weed seedbank at harvest, making the cover crops and herbicide applications more effective. “Reducing the seedbank in these rotations is very important to maintaining sustainability and profitability in the rotation,” he says.

Despite kochia’s resilience to temperature and herbicides, it is not invincible. This study demonstrates that even with low seasonal rainfall, using residual herbicides with cover crops can effectively suppress the majority of kochia emergence in a field while providing added benefits like enhanced soil health and reduced soil erosion. Visit GROW’s weed page on kochia to learn more about its biology and how to combat it.

Text by Amy Sullivan, GROW; Header and feature photo by Vipan Kumar, Cornell University.