Do you loathe Canada thistle? Do you marvel at field bindweed’s “indomitable vitality,” and occasionally leap from your vehicle (or horse) to hand weed the side of the road?

If you answered yes to any of those, then you have much in common with 19th century American farmers – and an early scientist who tried to help them!

This reminder of the timeless nature of agriculture’s weedy battles is thanks to a Mississippi State researcher, Dr. John Byrd. In 2023, Byrd and a team of researchers read, analyzed and reviewed the country’s very first weed management textbook.

The vintage weed manual they explored was written in 1872 by Dr. Ezra Michener, a self-described country doctor and farm manager. Like many of its precepts and weeds, the manual’s title could have been ripped from GROW’s very webpages: “The Weed Exterminator.”

“Agriculture is a perpetual conflict with aggressive plants,” Michener penned as the first sentence of his textbook. “All plants become weeds, in an agricultural sense, when found growing where they deteriorate other crops, needlessly exhaust the soil, or otherwise, bring loss to the agriculturalist.”

Michener took deep offense to the spread of weeds and to the people who neglected them. On one page, he scolds the citizens of Port Deposit, Maryland, urging them to unite and work together to eradicate a “repulsive weed” (spiny cocklebur) he encountered there, framing it as a patriotic duty. “When invaded by such a foe, every man should feel himself an appointed guardian, and defender of his country’s best interest and battle nobly for its utter extermination,” Michener urges, noting that he often leaps from his horse or carriage to rip offending weeds out of road ditches. And he wields a rich vocabulary of slurs and insults to describe the “slovenly, would-be farmers” who let their weeds become their neighbors’ problems.

Yet despite its aggressive title, The Weed Exterminator showcases the reality of the slow, incremental pace of manual labor in 19th century farming. At one point, Michener suggests that everyone take a tack from his neighbor, who sent two small boys to remove every oxeye daisy from roadsides and fields that couldn’t be reached with a plow. Michener brightly assures readers that this tactic will clear up that problem in a brisk “very few years (8 or 10).”

Troublesome Weeds (of 1872)

“The intelligent operator,” Michener says, will start their weed management by studying each weed they face carefully, so their management matches its biology. For example, he rightly notes that while tillage will control some weeds, such as annuals, it will increase “rhizomatous, bulbiferous and tuberiferous” weed populations.

To that end, he created long lists with the top most troublesome 100 weeds of his era, organized by annuals, biannuals, non-spreading perennials and creeping perennials. (Byrd and his fellow researchers organize these lists in easy-to-read tables in their paper.) Michener doesn’t go into management details for each weed, except for a handful that he finds most troublesome.

Today’s farmers will find some familiar names among those most problematic weeds tormenting growers 150 years ago. Canada thistle tops Michener’s list. He ranks it as “one of the vilest pests” in American agriculture, and suggests farmers try just about every tactic against it, from plowing to hand removal and primitive herbicides.

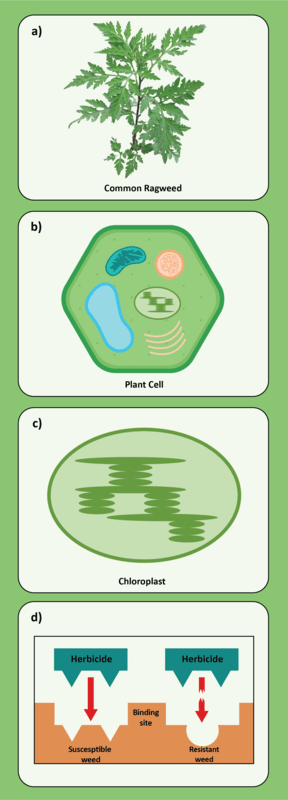

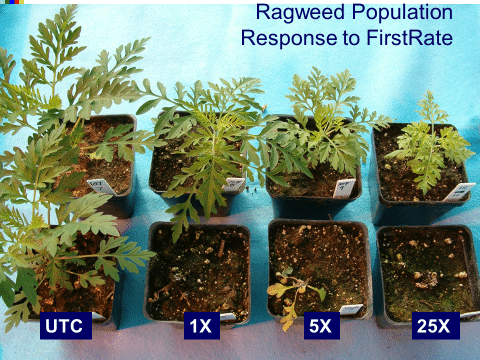

Common ragweed makes an impression, as well. It is so widespread that Michener calls it “The Weed,” and frets that annual tillage is somehow encouraging its seedbank to flourish. He credits an old housekeeper of his with a winning strategy for it: Simply prevent seed production for seven years, and it will be eradicated!

Field bindweed inspires an entire page of the textbook, and Michener recommends “smothering” as the best course of action against this weed’s “indomitable vitality.”

Other familiar targets on Michener’s hit list include common lambsquarter, shepherd’s purse, dandelion and wild garlic. Weeds that were toxic to humans and animals also got special notice in the textbook – think poison ivy and oak, certain nightshades, some hemlock species and common St. Johnswort.

Other weeds of the 19-century farmer are more obscure, but Michener’s description of the woes they create will certainly be familiar to any modern farmer or gardener. He speaks a great deal about a weed called yellow toadflax (Linaria vulgaris). He calls it “the most hurtful plant” in pastures that seems impervious to plowing, hoeing or even burning. It is with great pleasure that he describes finally eradicating it by smothering it with piles of weed stubble five feet deep, covered in 50 lbs of lime, and trampled down by cattle.

Vintage Weed Principles Look Familiar

Overall, Byrd and his fellow researchers tease out and describe the seven general principles for weed management that Michener penned. Note that some are familiar enough to be linked to our own GROW weed management pages!

- Never let weeds go to seed.

- Don’t till rhizomatous plants. (Michener compared this to spreading “the leprosy spot”).

- Scout and remove all perennial roots.

- Target plant leaves, as they are the plants’ greatest vulnerability, the source of “digestion, assimilation, and respiration.”

- Aim to destroy and remove leaves all season long. Michener claims Canada thistle has been eradicated by continuously removing stalks through June, July and September.

- Practice hand removal by any means; he mentions tillage, mowing, cultivation, harrowing, suffocation with mulch or straw, poison (herbicides) and “high farming,” his term for essentially helping your crop out-compete the weeds.

- Stay vigilant and never stop scouting even once fields look clear. “Continued watchfulness, and prompt action, as long as the danger exists,” as Michener puts it, with characteristic flair.

Other management tactics, such as burning, get a weak review from Michener, who once had poor luck eradicating Scotch cottonthistle in a burn pile.

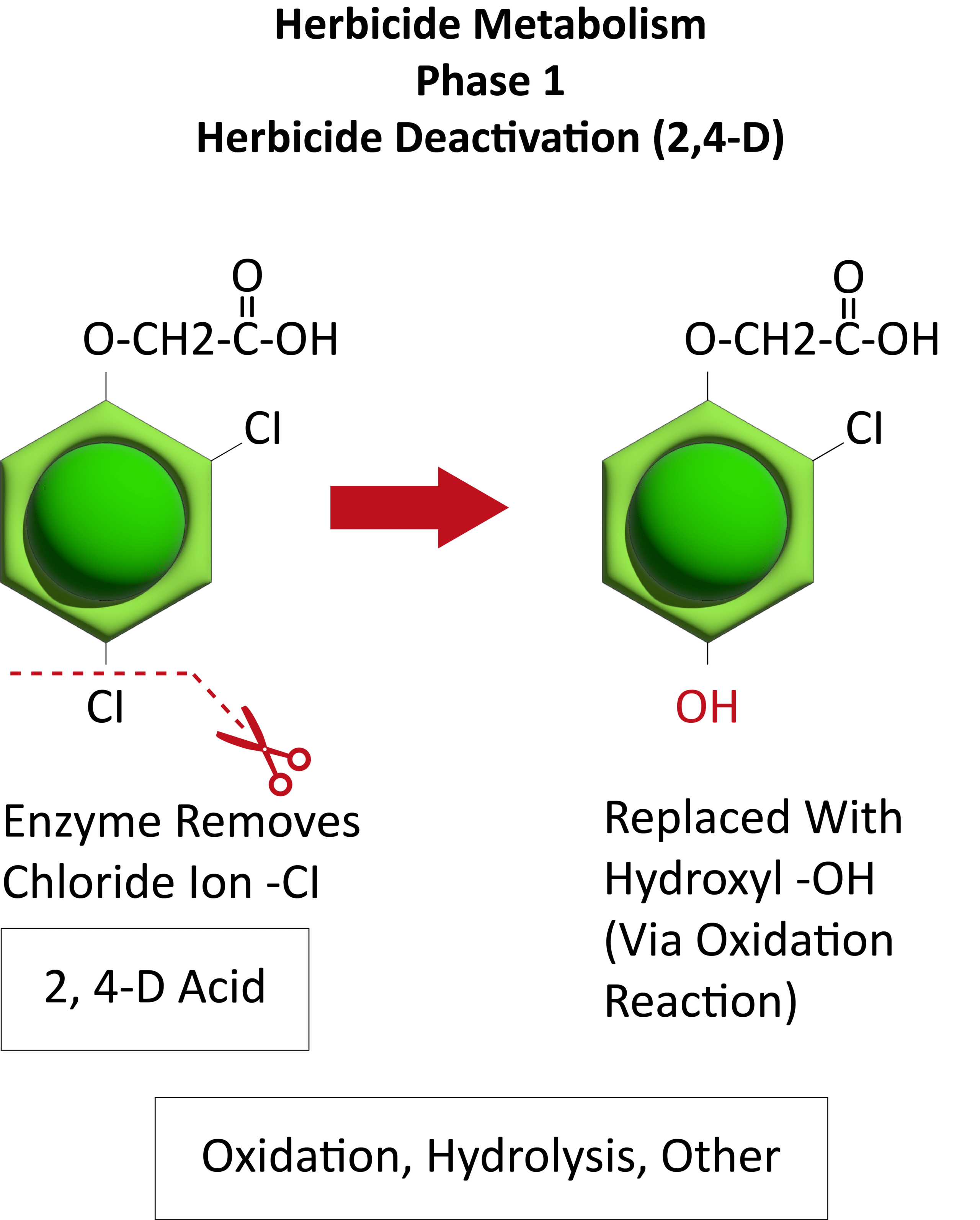

Herbicides of the day are primitive, imprecise, and get only a few passing references as “poisons.” In one passage, Michener recommends applying a mixture of 3 parts salt to 1 part “copperas” (FeSO4), to the cut stalk of his archenemy, Canada thistle plants. With somewhat disturbing relish, he writes that the goal is to reach the roots, with “the juices of the parent carrying the poison to its attached and still dependent offspring.”

Farmers, Attention!

Before outlining his principles and common weed management tactics of the day, Michener sets aside a dramatic section just to scold bad weed managers, titled “Farmers, Attention!” In it, he notes that weeds are a community problem – individual landowners can make big problems for their neighbors.

He has a dim view of these kinds of farmers and slings a series of imaginative insults their way.

“The sluggard occupant, I will not call him ‘a farmer,’” Michener writes, “is often a worse nuisance to neat farmers than his foul, and neglected, fields.”

He labels their weed-infested fields as “a national disease” and waxes dramatic about the rights of farmers and citizens in the face of these problematic weed spreaders. Since authorities were allowed to enforce quarantines for certain human and animal diseases, Michener argues that a similar authority should exist for weeds.

To that end, he proposed forming “agricultural boards of health” in different districts to oversee and regulate clean grain sales and inspect farms for noxious weeds. The agents of these boards would even be called upon to haul offending farmers off their own property and seize control of their fields, until their weed infestation was under control.

“You may call these suggestions bold,” Michener admits. “…[but] They are founded upon the solid and universally acknowledged basis of equal, and reciprocal, rights, which underlie and sustain all rightly constituted, social and political organizations.”

Want to read Michener’s manual for yourself? You can find a PDF version of it from WSSA here. Or simply peruse Byrd’s article here, for a quick, authoritative summary of the manual.

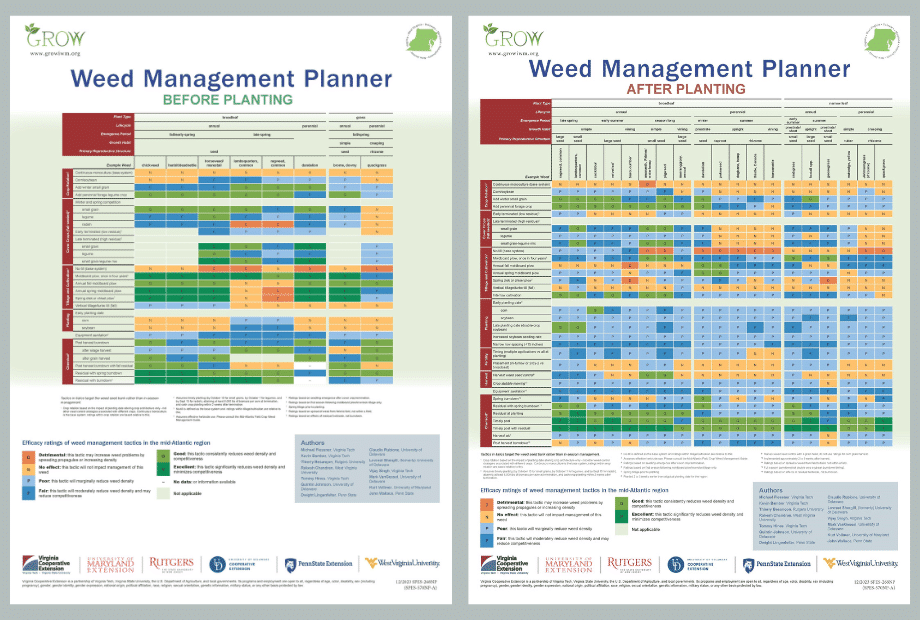

Looking for more up-to-date advice for weed management tactics? Visit GROW’s ever-expanding Weed Management Toolbox.

Article and feature photo by Emily Unglesbee, GROW; header image courtesy Virginia Tech Weed ID Guide.