Imagine a cover crop that never stops growing — nestled between the rows of a cash crop, continuously suppressing weeds and supplementing the soil. Would this practice, known as “living mulch,” work in southern cotton fields? Could it help farmers facing the fiercest of weeds — Palmer amaranth?

That’s what my research team at the University of Georgia is exploring, under the direction of Dr. Nicholas Basinger. While the answers aren’t clear yet, we are learning how different types of cover crops — cereal rye, crimson clover and living mulch — affect weed emergence, growth and seedbank.

See a video on our research here:

The Target: Palmer Amaranth

One of the greatest hindrances facing Georgia cotton producers is Palmer amaranth. Palmer amaranth is a highly fertile and widespread weed in the Southern U.S., with the ability to produce a million seeds from one single female plant, under ideal conditions. Up until the last two decades, herbicides were the primary weed management option producers had. But, due to heavy reliance on herbicides, increases in herbicide-resistant weeds have created biological roadblocks to weed control.

Within the past decade, researchers recommend the use of integrated weed management (IWM) practices. Practices include planting date selection, crop rotation, and using cover crops to minimize weed emergence. Cover crop use is one integrated management practice potentially well suited for Palmer amaranth management in Georgia cotton production.

Producers can utilize a range of cover crops, such as annual grasses (cereal rye, wheat, oats, and triticale) and legumes (Balansa clover, crimson clover, white lupin, and common vetch) or perennial living mulches (Durana white clover), which can alter Palmer amaranth population dynamics, reducing weed competition. In the last decade, the idea of a “living mulch,” a continuous cover crop growing between crop rows, has just been introduced to Georgia row crop production as a cover crop option by Dr. Nick Hill, a professor emeritus at the University of Georgia, and an Extension agent for the CAES Newswire, in Athens, GA.

Living Mulch Research

Dr. Hill and Dr. Basinger have discovered that the use of white clover as a living mulch in field corn has great benefits to weed suppression and nitrogen fixation characteristics for the crop. Using a legume cover crop as a living mulch provides a continuous source of nitrogen released into the soil via dead vegetation while also providing a weed suppression barrier. Our research team was inspired by these findings, and decided to see how it would work in Georgia cotton production.

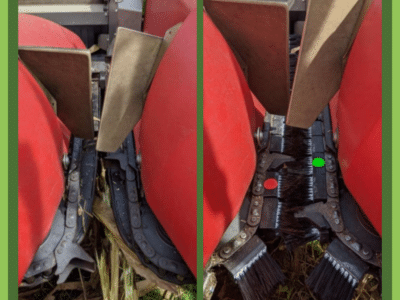

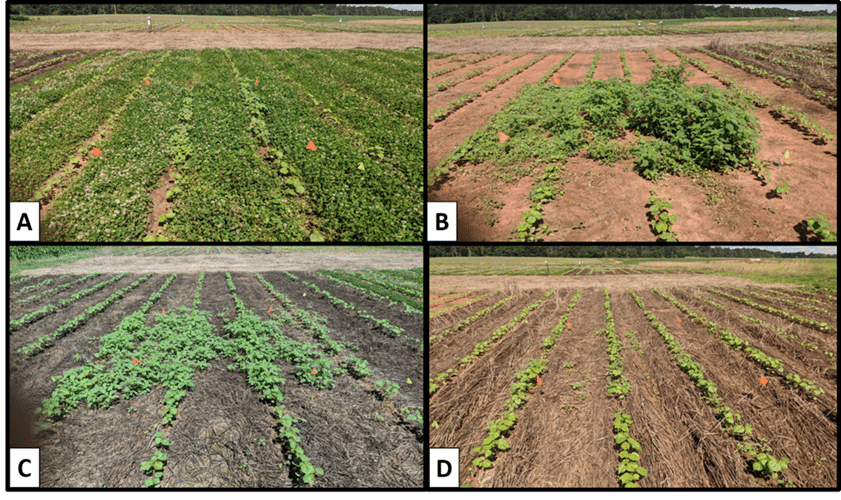

We set up a trial in 2020 to observe living mulch’s impact on Palmer amaranth populations in Georgia cotton, as well as the impacts of cereal rye and crimson clover compared to no-till practices for four years. We did not use post-crop emergence or residual herbicides in years 1 and 2, primarily because the cover crop effect on Palmer amaranth was our focal point.

Since 2020, we saw shifts in cover crop and weed material occurring based on cover crop type. In year 1, cover crop biomass was abundant, but in years 2 and 3, cereal rye, crimson clover, and living mulch biomass began to decline. One theory is that during year 1, the land had no prior cotton production, so cover crops could be planted within the optimal sowing window (mid-September to late October) resulting in considerable biomass. But with cotton harvest usually occurring in late October to early November, we missed that sowing window in years 2 and 3. It is also important to note that since this area had no prior cotton or crop production, there was no history of Palmer amaranth populations. Nevertheless, between years 1 and 2, the number and size of Palmer amaranth plants were similar.

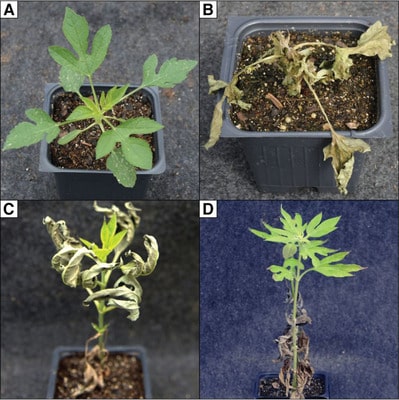

In the end, cereal rye and living mulch cover crops greatly reduced the total number of Palmer amaranth plants in year 1 and 2, but not the number of seeds or biomass produced per Palmer amaranth plant. Living mulch created an environment that caused individual female Palmer amaranth plants to produce between 9,570 and 19,800 more seeds and 38% to 60% more biomass than if they were exposed to cereal rye, crimson clover, or bare ground (no cover crop) conditions.

Adding Herbicides Into The Mix In Year 3

During the 2022 cotton season, a contrasting story unraveled. We sprayed three applications of Glufosinate-ammonium at 32, 32, and 23 fl oz/ac during three dense Palmer amaranth seedling emergence flushes to determine the effects of post-emergence herbicides. This changed the outcome and characteristics of a two-year-long Palmer amaranth population.

Before, cereal rye and living mulch alone reduced the number of Palmer amaranth observed at the end of the season. Now, glufosinate applications to cereal rye, crimson clover, and bareground reduced the number of Palmer amaranth plants. But because we could only spray vegetation-free strips (the cotton rows) to preserve the living mulch, Palmer amaranth populations increased in those plots.

Also, the living mulch cover crop at year 3 had poor stand and biomass coverage, which created inadequate barriers for weed suppression and likely also increased Palmer amaranth counts. Despite the sizable increase in Palmer amaranth plants, seeds produced from an individual female plant only reached 7,413 seeds. Inadequate living mulch barriers allowed for more Palmer amaranth plants to emerge, which in turn, created a higher chance for competition for essential nutrients and lessening the plants’ ability to be highly fertile.

All things considered, the type of cover crop that you select, whether an annual grass or legume or a perennial grown as a living mulch, definitely affects Palmer amaranth populations in your cotton field. The application of post-emergence herbicides, such as Glufosinate-ammonium, is also crucial in further combating a troublesome weed species. When we have the combination of a physical barrier (cover crop) and a broadcast herbicide application, Palmer amaranth populations are almost completely controlled. Legume cover crops also add extra nitrogen back into the soil at either the beginning of the season (crimson clover) or continuously (living mulch). And while living mulch also has the upside of reduced herbicide cost, you still have room for escaped Palmer amaranth plants.

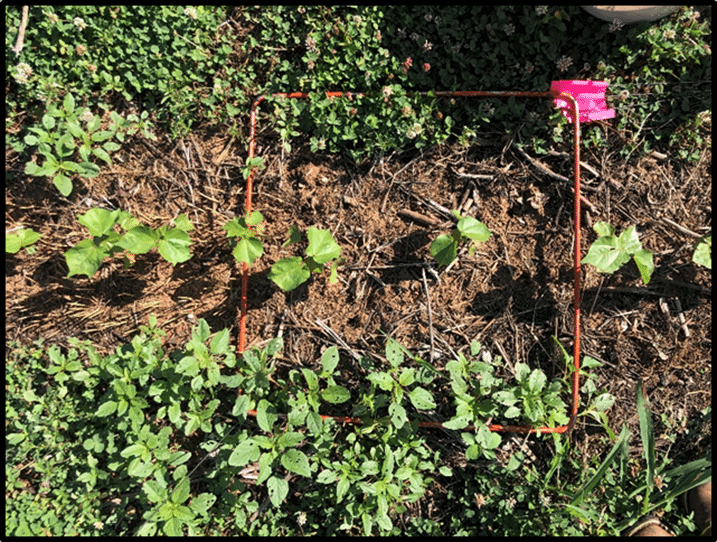

The Death of a Weed Seed

My team also examined how various soil environments – like the living mulch one – affected how weed seeds degraded over time. Watch a video on that aspect of our research here:

For more information on managing cover crops to suppress weeds, see this GROW webpage.

Article and photos by Hannah Lindell, University of Georgia

Videos by Claudio Rubione, GROW.