Listen to this article above!

A mystery was cropping up in southern Texas. “We’ve done a lot of research on cover crops, and every time we had a cereal rye cover crop, we noticed less johnsongrass in the field,” recalls Gustavo Silva. A master’s degree student at the time, he and his colleagues dug up the cover crop plots and found far fewer johnsongrass rhizomes where cereal rye had been planted.

So in 2024, Silva launched a two-year study to better understand this phenomenon, and preliminary data revealed surprising results: Cereal rye significantly suppressed johnsongrass rhizome biomass, rhizome node number, and regrowth plant biomass. Silva posits that this annual cover crop could be part of a successful weed management strategy in conventional and organic operations. This summer, he’s replicating the trials to further explore his theory.

Now a doctoral student at Texas A&M University in College Station, TX, Silva is conducting the research for his dissertation, under the supervision of his advisor, TAMU weed scientist Dr. Muthu Bagavathiannan, and with assistance from undergraduate researcher Kaitlyn Booth.

They conducted the first year of the study in the university’s research plots, where johnsongrass grows in abundance. It’s a perennial grass that reproduces quickly through seeds and rhizomes – underground stems that tunnel through the soil, launching new shoots and roots from nodes. Young seedlings resemble domestic corn or sorghum, and mature plants produce tillers that grow two to eight feet tall.

“Johnsongrass is a big problem in the southern U.S.,” Silva says. In the northern U.S., freezing temperatures keep it at bay. But it’s very aggressive and well-adapted to the South, “where the roots do well even in dry, 120-degree weather.”

It’s difficult to control johnsongrass, especially in organic fields, Silva notes. Tillage is the most common control method, but it has to be timed carefully to either freeze or cook the chopped rhizomes on the soil surface before they can grow new shoots and roots. Mowing, plastic mulch, and flooding are other controls, but the most effective is manual hoeing, he says, a time-consuming prospect.

Digging in the Dirt: The Research

When preparing for his study, Silva found that research on cereal rye’s capacity to suppress perennial grasses was limited. Past studies documented that cover crops do not reduce perennial weed density but did not observe underground plant structures such as rhizomes. He hypothesized that a cereal rye cover crop would suppress johnsongrass rhizome winter survival and summer regrowth.

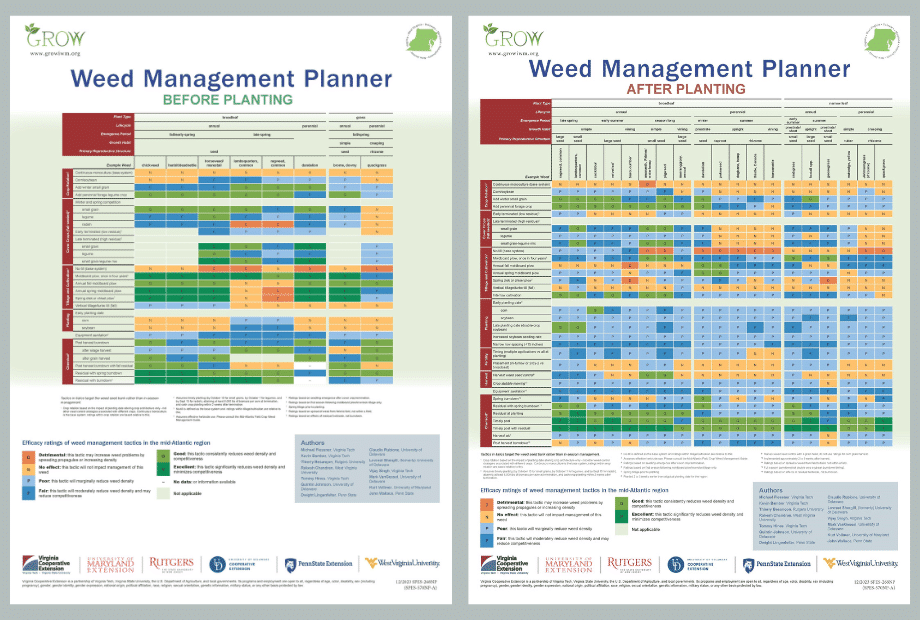

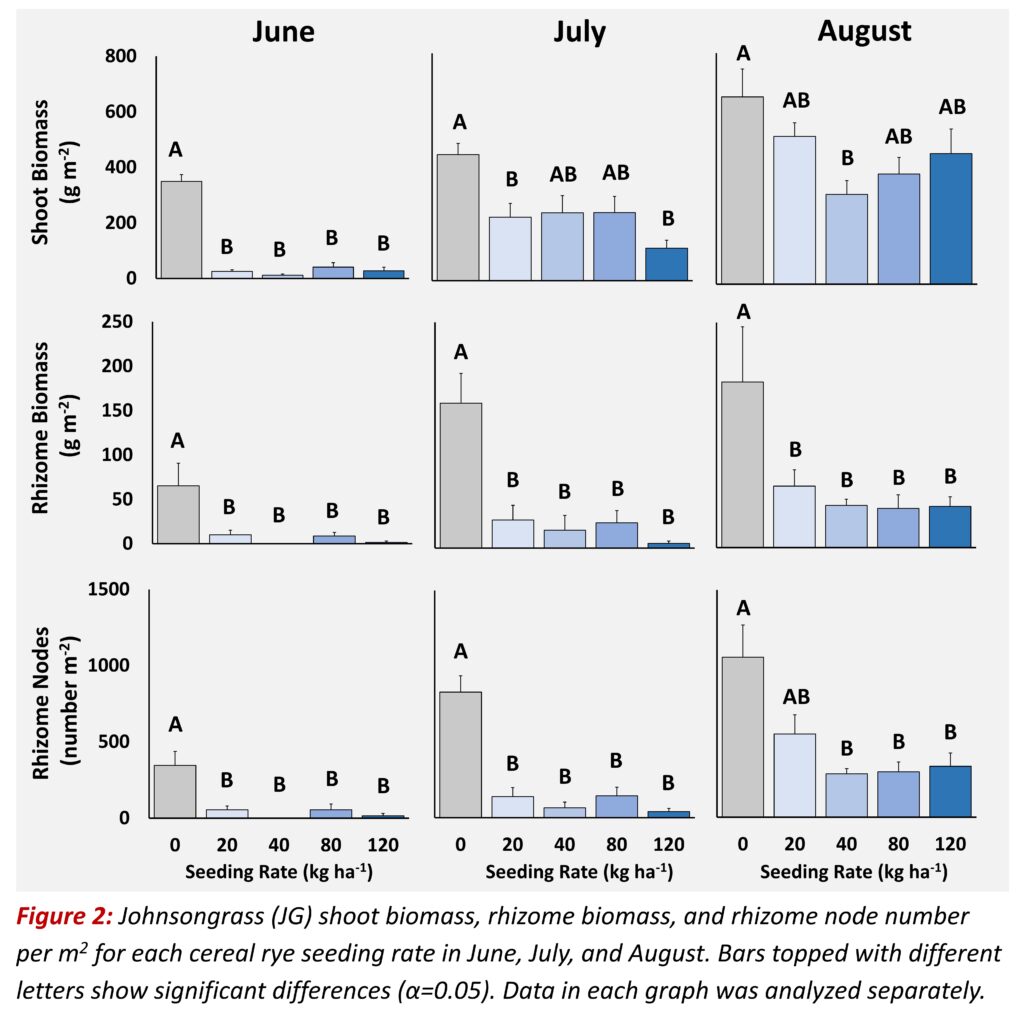

In the summer of 2024, he planted four replications of cereal rye with seeding rates of 0 (no treatment), 17.5, 35, 70, and 105 pounds per acre. He used organic management practices and measured the biomass of the cereal rye in May before terminating it with a roller crimper. In June, July, and August, he and Booth took three johnsongrass measurements: 1) the above-ground shoot biomass, 2) the below-ground rhizome biomass and 3) the rhizome node number.

A Formidable Foe: The Results

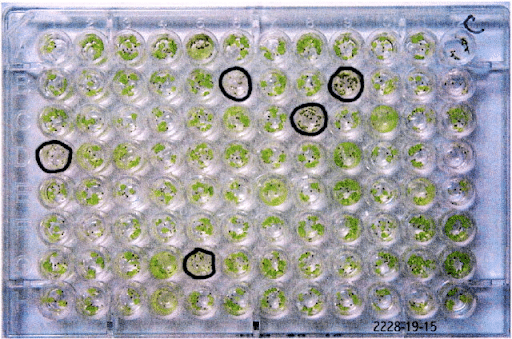

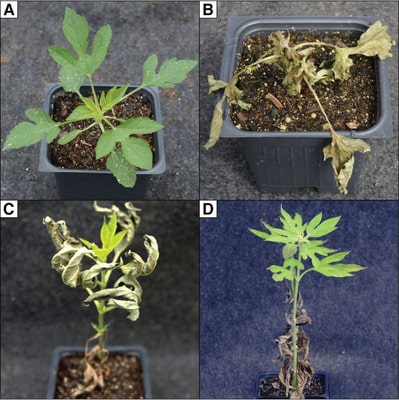

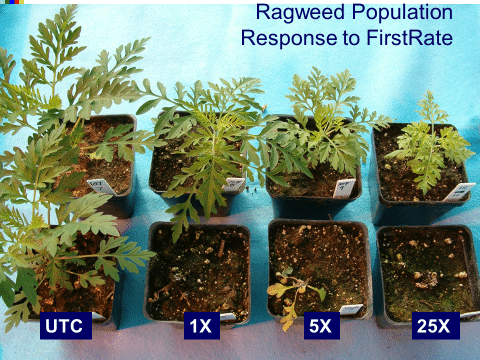

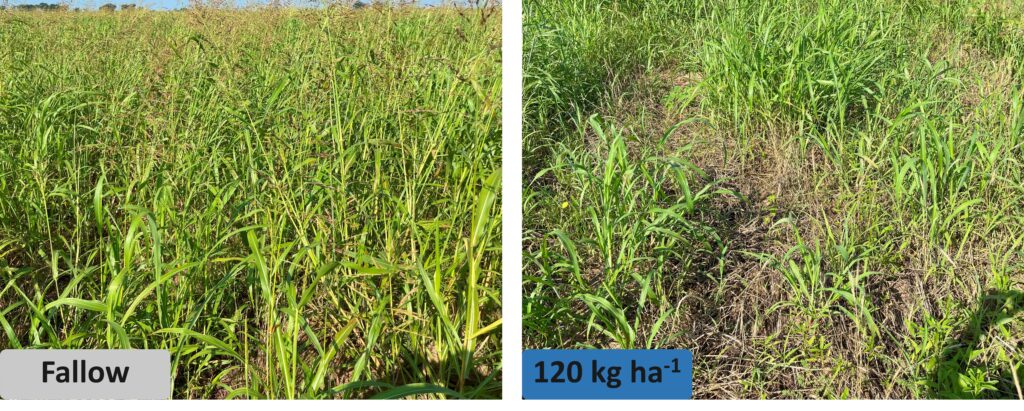

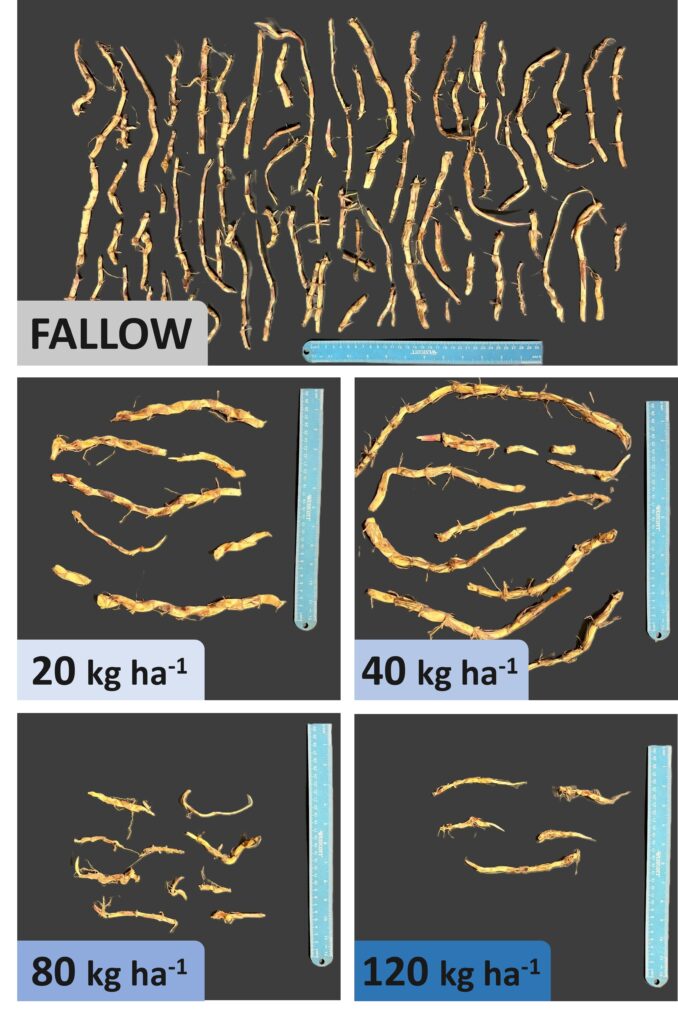

Figure 1 shows photos of johnsongrass rhizomes that Silva and Booth collected from a one-half-square meter section of each cereal rye seeding rate plot in July. The images show that the higher the seeding rate, the lower the number of johnsongrass rhizomes. These data proved statistically significant, as did data for all seeding rates in each of the three months.

For example, June data showed that cereal rye suppressed johnsongrass rhizome biomass by 84%, the rhizome node number by 88%, and regrowth plant biomass by 68%. And all seeding rates of cereal rye suppressed rhizome biomass by 86% through July and by 75% through August.

“Wherever the cover crop grew, there was a significant reduction in johnsongrass rhizome production,” Silva says. “We didn’t expect that much of a difference.” The cover crop also delayed rhizome resprouting and above-ground growth, Bagavathiannan says.

Incidentally, data showed that the cereal rye seeding rate did not have a measurable influence on final cover crop biomass, which averaged 3,600 pounds per acre. On average, growers can plant 35 pounds per acre to achieve the desired biomass and johnsongrass suppression effect.

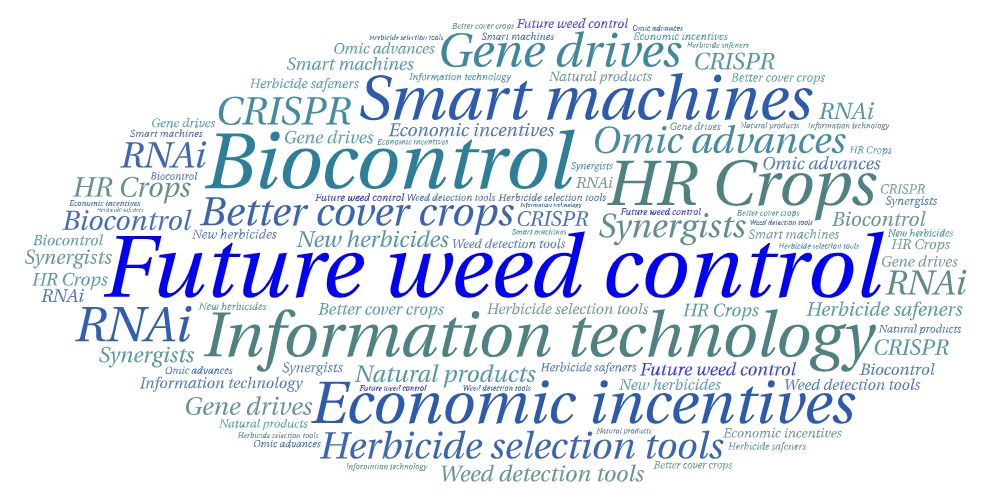

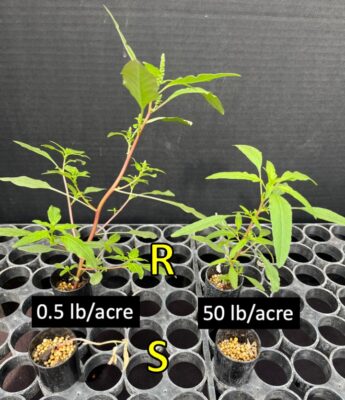

This summer, Silva will replicate the trials to see if weather variability or other factors out of growers’ control might impact results. But his preliminary data show that cereal rye effectively suppresses johnsongrass rhizomes and, in turn, shoot regrowth potential (Figure 2). It can be a powerful tool for long-term management of this perennial problem when paired with other weed management strategies.

“Cereal rye is not a silver bullet; it won’t fix all your problems, but it will help,” Silva says. “It can do 80% of the job, but you still have the 20% to deal with through things like mulching, hand weeding, some tillage, and chemical control if you’re not growing organically. Otherwise, the remaining johnsongrass will quickly take over the field again.” The only thing Silva doesn’t know is exactly how cereal rye suppresses johnsongrass. It could be through underground competition or through allelopathy, a process by which plants produce chemicals that disturb the growth of other plants. That, says Silva, is a question for his next study.

“We are very excited about the potential of cereal rye to decimate perennial underground vegetative structures,” says Bagavathiannan. “For some time, we speculated about this possibility based on anecdotal observations, and Silva’s research now provides clear evidence to support it. I am confident this finding offers a novel non-chemical management tool for johnsongrass, particularly in organic production systems, where it has long presented a major challenge.”

This research was supported in part by a USDA-NIFA Organic Transitions (ORG) grant and an Organic Research and Extension Initiative (OREI) grant.

Article by Dr. Elizabeth Seyler, University of Vermont Extension