Listen to this article above!

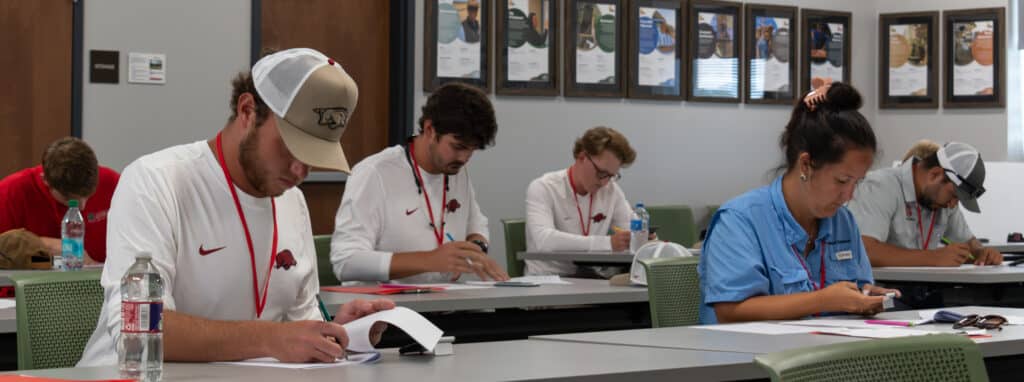

It’s barely 8:00 in the morning when the crowd scatters outside the University of Arkansas Extension Center in Newport, Arkansas. The 104 students — armed with clipboards and outfitted in school colors like Georgia’s Bulldog Red, Auburn’s Burnt Orange, and Arkansas’ Apple Blossom White — duck into metal buildings, climb onto trailers, and stride toward nearby fields. Students in the Northeast and Midwest made similar journeys to Extension centers and company research sites over the summer, all for weed science’s version of the Olympics: student weed contests.

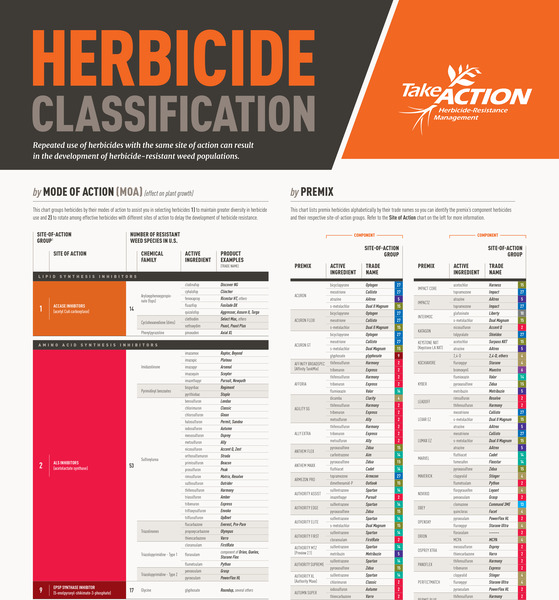

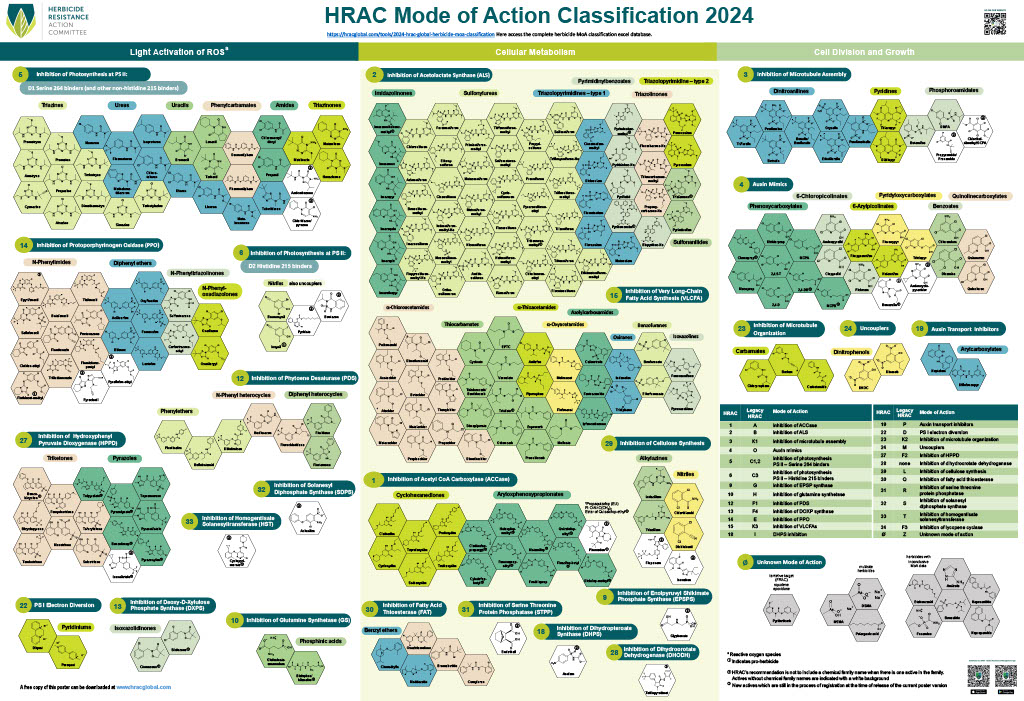

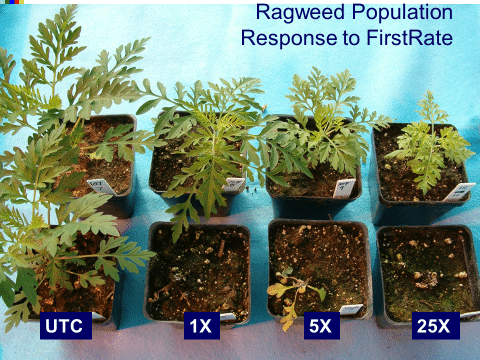

These contests are an opportunity for students to show off everything they know about weed science. Students study months in advance for the day’s competitions: a written herbicide calibration test, weed identification test, team herbicide calibration exercise, herbicide identification exercise, and – perhaps most importantly – in-field farmer problems.

The weed contests date back to 1980, when the Eli Lilly Research Farm in Albany, Georgia hosted four southern land grand universities in the first ever “Deep South Weed Meet.” The Southern Weed Science Society (SWSS) and North Central Weed Science Society (NCWSS) saw the student benefits in this contest and held their first competitions in 1981. Other regional societies quickly followed suit. Today’s contests closely resemble that first competition 45 years ago, down to the elite squads of three to four students brought in to represent their weed science departments.

Preparation for the Big Day

Each university prepares their students as best as possible to take home those first place bragging rights.

Some universities, such as the University of Arkansas, hold mock weed contests ahead of the big day. Other universities hold semester-long preparation classes. All universities encourage self-led study, and some weed science graduate students such as Danny Zhu (University of Wisconsin) pitch in to help undergraduates prepare for the contests.

But not everything can be taught in the classroom. The communicative soft skills needed to solve farmers’ issues are best developed in mock real-world situations, Dr. Greg Dahl notes.

Dahl, a former Weed Science Society of America president, NCWSS president, and retired WinField United weed scientist, attended his first ever weed competition in 1982 as a member of North Dakota State University’s team. He took home the third place individual prize. His team won first overall. He has since volunteered at over 10 student weed contests, often role-playing the problem-riddled farmer.

Students and contest organizers alike cite the farmer problems as one of the day’s trickiest competitions. The problems are meant to shake up students and show them what communication skills they need to improve before they consult with actual farmers, Dahl says.

It’s a daunting setup, but one that’s appreciated by the students. “It gives you a bit of practice in an environment where you can fail,” Zhu explains.

Zhu’s own undergraduate transition from agricultural engineering to agronomy left him with gaps in his communication skills that the contest’s farmer problems helped fill, he recalls. “It was a big change to talk to growers about their operation,” he explains. “So in terms of getting with growers and talking to people in the Extension world, the ability to communicate and be professional was something that really helped from the contest.”

Those communication skills benefit all students, regardless of education level or career aspirations, says Sarah Chu, a recent doctoral graduate from Texas A&M and four-time SWSS contest participant. “The problems put you in the worst-case scenario, but it prepares you for the best,” Chu explains. “You learn how to create your line of questioning, and you also learn how to calm someone if they have a total crop failure.”

Chu’s explanation highlights the benefit of including everyone, from undergraduates to non-weed science majors, in the contests. This is one of the few changes that each society made after the initial competitions.

The regional competitions also train students for the national student weed contest. It’s an event held every four years by the Weed Science Society of America.

Those Behind the Scenes

Volunteers are critical to the contests. “It wouldn’t be possible without a lot of people volunteering their time,” Chu says. “It really shows the community’s investment into the students.”

“We need these students to come in and solve the problems that we have today, and the problems that are going to crop up in their career.”

Greg dahl

Volunteers oversee competition set up, breakdown, and competition proctoring. They are often industry professionals, academia, private researchers, and crop consultants, which creates many networking opportunities for the students.

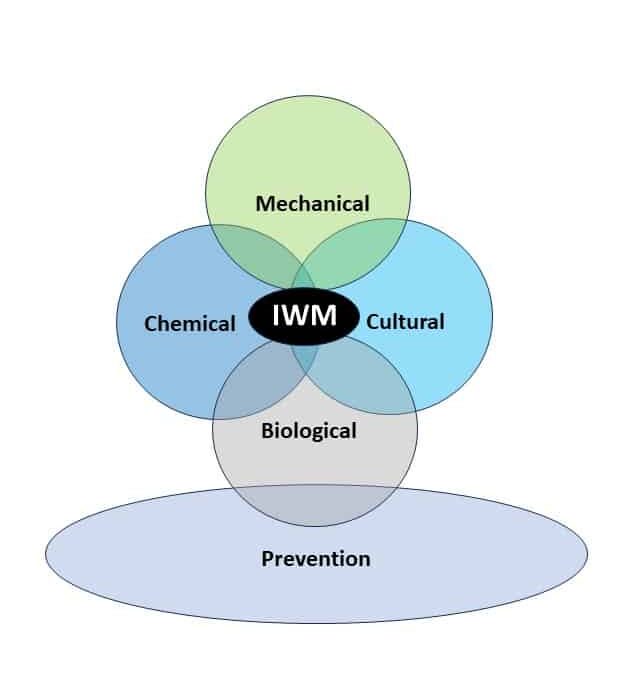

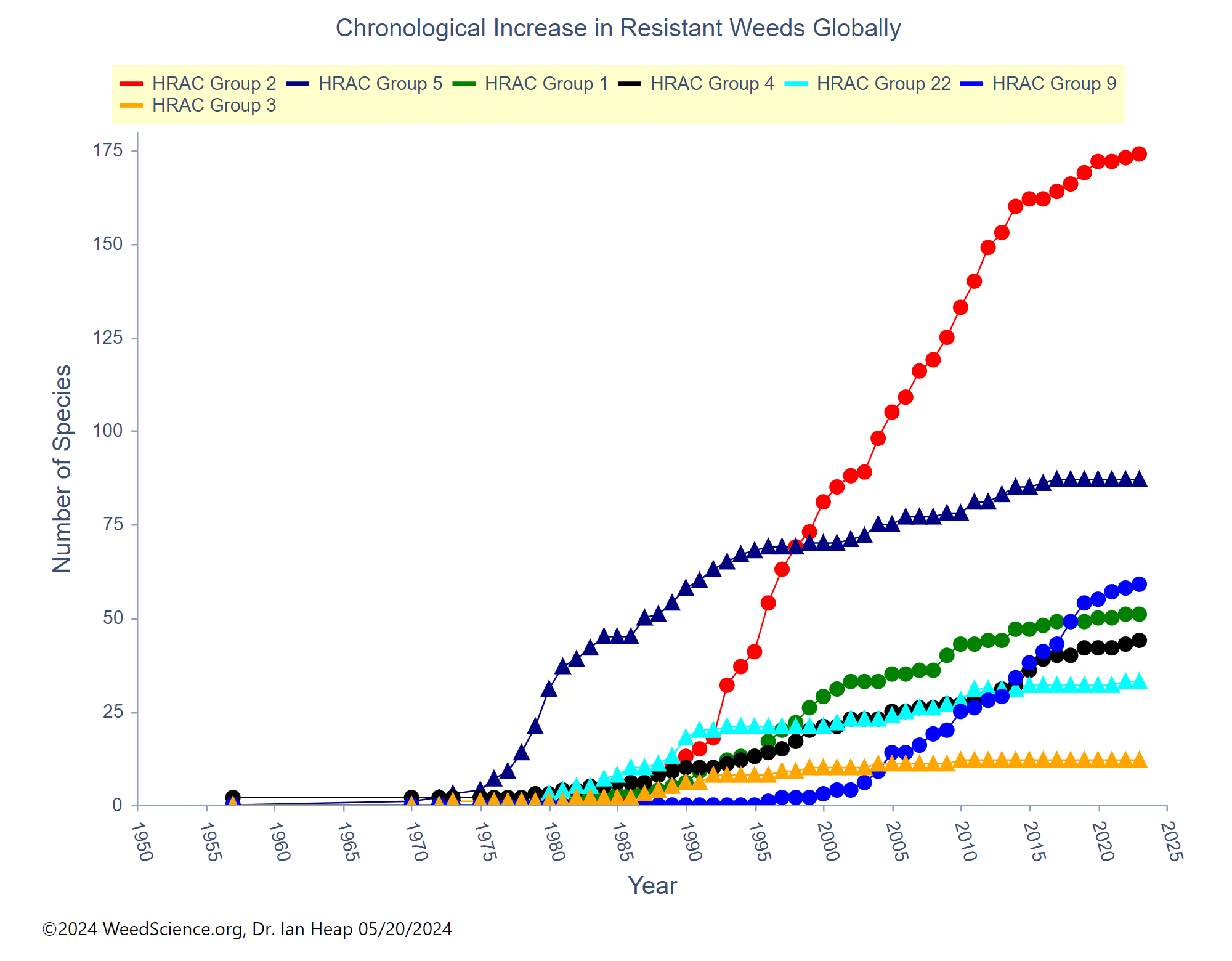

This community investment in students helps fuel the future of weed science, Dahl says. “We need these students to come in and solve the problems that we have today, and the problems that are going to crop up in their career,” he shares.

Overall, the contests are meant to ensure students are prepared for their careers in weed science, covering everything from practical knowledge to confronting issues in the field. Dahl also has one recommendation for students intimidated by the contests: “It’s okay to be afraid. Come anyway, prepare the best you can, but you won’t know everything.”

But that’s not to say that the competitions aren’t packed with students eager to show what they know. The 2025 SWSS contest hosted 104 students, some of whom took a 14-hour trek just to attend.

Interested to know how the contests play out? Below is a peek into the 2025 SWSS student weed contest.

Herbicide Calibration Test

This portion of the contest has air conditioning, but the students are still sweating. Imagine a standardized test, but with herbicides. Students hunch over tables with pencils and calculators in hand, working out problems as a 45-minute timer counts down. Two proctors watch closely as students calculate answers for questions such as, “How many gallons per minute does this sprayer deliver?”

Weed Identification Test

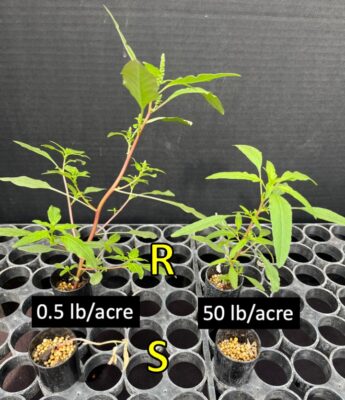

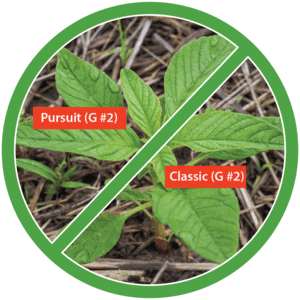

Here, potted weeds and vials of seeds line tables throughout a metal room. One weed species even floats in a mock-aquatic environment. Students quietly shuffle around each other, examining the underside of leaves and squinting at the shape and color of seeds before they scribble weed identities on paper. Graduate students need to know 100 weeds and weed seeds by their common and scientific names, from “smellmelon” to “ducksalad.” Undergraduates have things a bit easier; they only need to know common names. Yes, spelling and capitalization count.

Herbicide Identification

Name that herbicide!

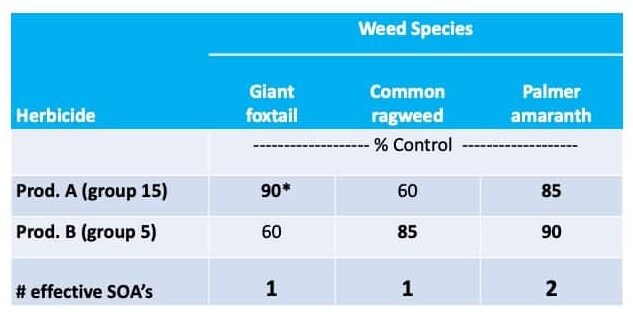

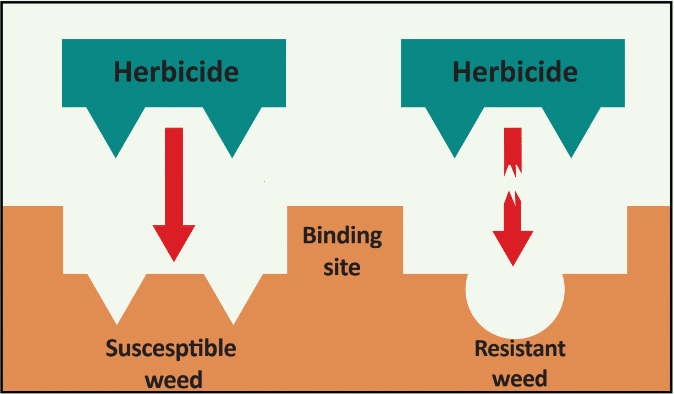

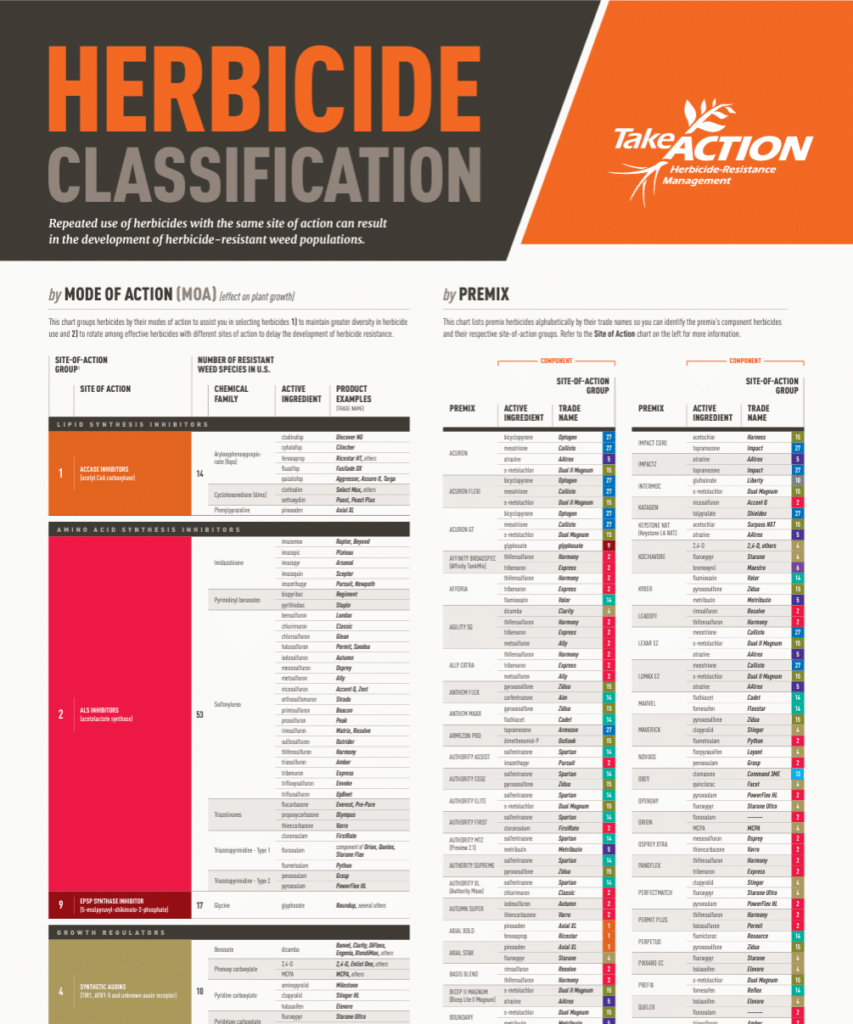

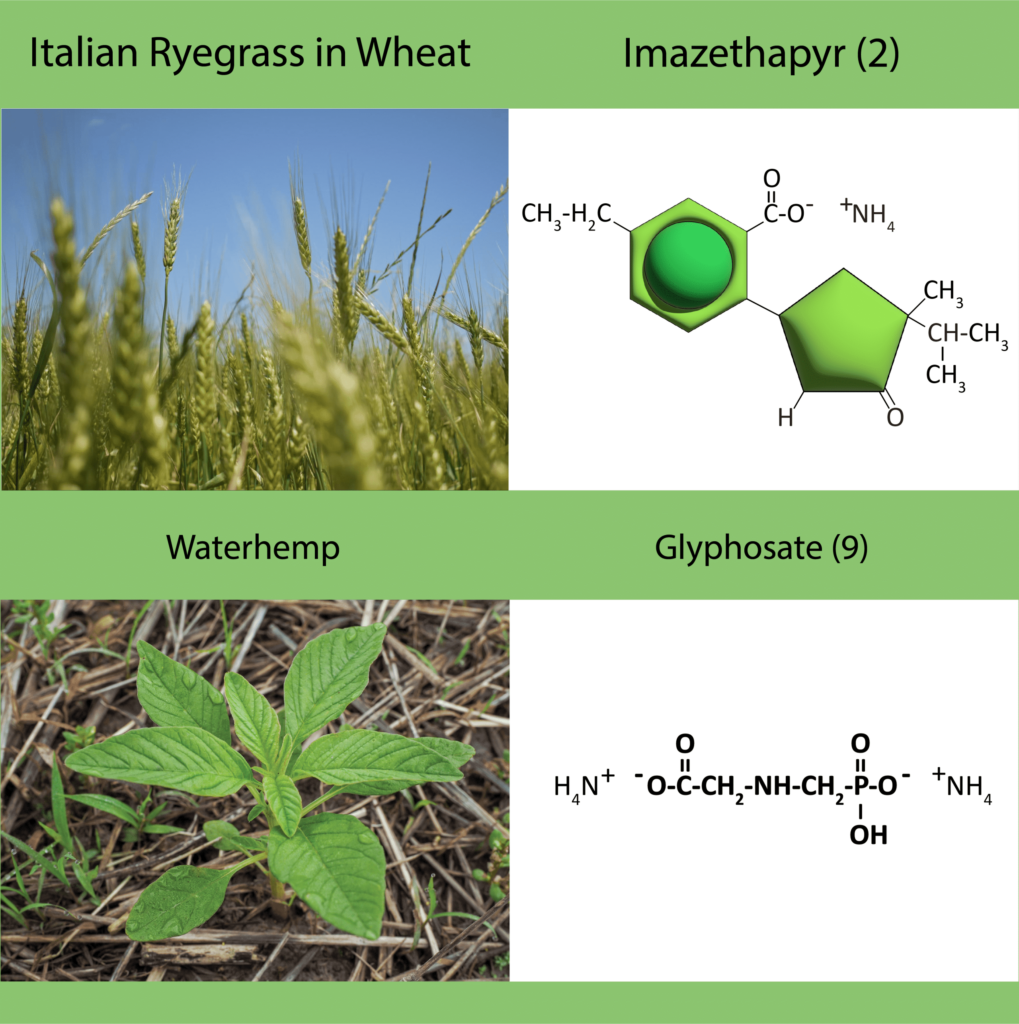

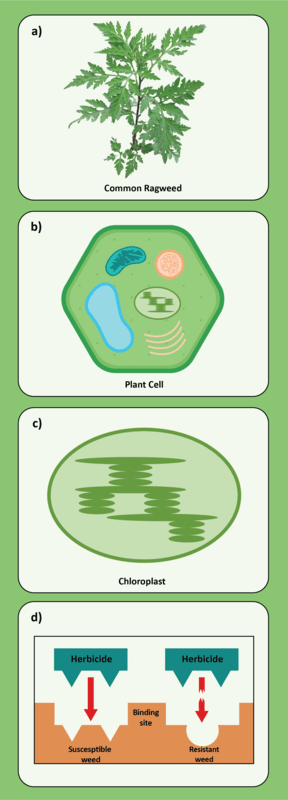

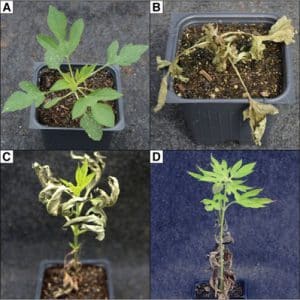

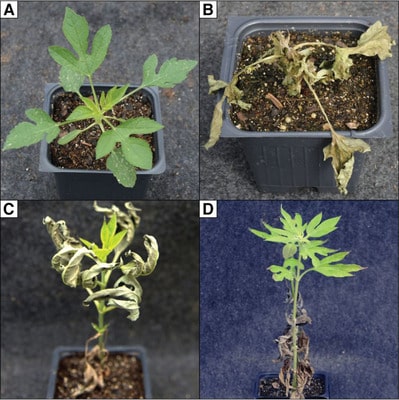

The heat cranks up as students head outside to scrutinize several plots with six weeds and six crops. Each plot sports various symptoms of weed and crop injury. The student detectives have to identify what herbicide was sprayed on which plot (including the herbicide’s family and group number), all while the sun beats down on them from above.

Team Herbicide Calibration

Two teams from different schools cluster around opposing tables. They must calibrate a backpack sprayer in just 20 minutes. The words of the exam proctor hang over them, “No one has gotten this right today.”

The students are a mix of careful and chaotic as they calibrate and strap the backpack sprayer onto a fellow team member. That volunteer then marches along a path painted on the ground, doing their best to adhere to the competition’s specific sprayer guidelines while also trying to avoid the innocent teddy bears placed as do-not-spray zones.

In-Field Farmer Problems

One farmer waves around an insect net, another points somewhere across the field, while other farmers and students crouch near the soil. Students must greet their farmer, learn about their farmer’s problem, and give recommendations for the current year’s and next year’s crop, all in just 15 minutes.

Nearby, an examiner dutifully takes notes on what the student did right…and what they did wrong. Notes from a SWSS annual meeting put it best, “For this event, luck may be better than knowledge.”

Some regions unwind the day with a lighthearted mystery contest (a component first introduced in the 1991 SWSS contest). The SWSS’ 2025 mystery contest, for example, was an egg toss with added egg-themed dares where students could gain extra points towards their overall score.

Each contest wraps up with an award ceremony and banquet. The first-place graduate team will take home a plaque (or, if you’re in the SWSS, a broken hoe trophy that travels with the winners each year).

Bragging rights are secured — but not for long. The cycle repeats when the fall semester starts, and students begin studying for the next year’s weed contest.

When they aren’t studying for weed science contests, many students play a role in advancing weed science research. Explore GROW’s website to learn more about this research, from weed electrocution to cover crops for weed suppression!

Article, header photo, and feature photo by Amy Sullivan, GROW.