Imagine taking a direct hit of 15,000 volts of electricity, as you stood in a wide open field, feet planted in the soil.

Now you know how it feels to be a weed on the Bradford Research Farm in Columbia, Missouri!

That’s where University of Missouri (UM) senior research associate Haylee Schreier spent two summers experimenting with The Weed Zapper, under the direction of UM Extension weed scientist Dr. Kevin Bradley. The work, which was funded by the Missouri Soybean Merchandising Council, was recently published in the journal Weed Technology.

The Missouri researchers tested how well weed electrocution works for common weeds in row crops, as well as how a crop like soybeans might survive a brush with electrocution meant for weeds.

The good news? The Weed Zapper proved quite capable of killing weeds, particularly broadleaves. It was especially potent against large, late-season weed escapes, which are hard for farmers to control currently. And the heavy electrical jolts delivered by the Weed Zapper delivered a fatal blow to the majority of weed seeds they encountered.

But Schreier’s research also uncovered some potential challenges. The team’s simulated electrical damage to soybeans nearly always resulted in some lost yields. And occasionally some weeds, particularly grasses and weeds at early growth stages, managed to re-grow after the zapping.

Schreier’s research aims to set a valuable foundation of knowledge about weed electrocution for the agricultural industry. At the moment, research on its efficacy in large-acre crops is scant, at a time when herbicide-resistance is making new weed control strategies more important than ever in row crop production.

Frying Weeds for Science

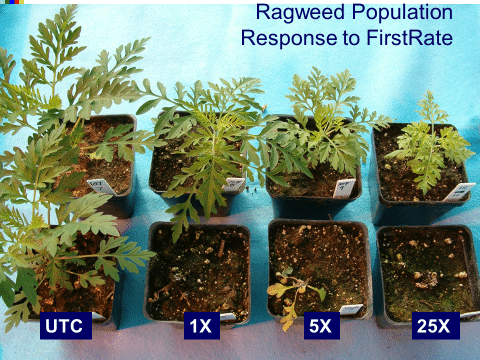

With a fire extinguisher tucked into the cab of a Case IH tractor, Schreier spent the summers of 2020 and 2021 pulling the Weed Zapper unit through fields bristling with cocklebur, waterhemp, horseweed (marestail), giant and common ragweed, barnyardgrass and giant and yellow foxtail. The shocks were delivered to these weeds at varying stages, including 12 inches tall, 24 inches tall, flowering, pollination and seed set.

As the tractor moved through thick patches, with an electrified copper bar mounted on the front, you could hear the engine of the tractor revving harder to power the pull-behind Weed Zapper unit supplying the electrical juice, Schreier recalled.

“Sometimes you could physically see the sparks flying off the bar,” she said. “It was pretty satisfying.”

The weeds, as you might imagine, enjoyed the experiment less. And the bigger they got, the worse they fared, a result which surprised the research team.

“We were shocked by that, because with herbicides, you obviously get better control when weeds are smaller,” Schreier noted. “But in this case, because the electrified boom can only go so low toward the ground, we saw better control when weeds were bigger, and when more of the plant could be contacted.”

The surface area of the plant hitting the bar might also partially explain why the Weed Zapper proved more effective against broadleaves than for the grass species of barnyardgrass and foxtail, Schreier added.

The wily ways of grasses likely played a role, too. “We think it has to do with the physiology of the plants,” she said. But more detailed research is needed in this area, she added.

Among the broadleaves, the only weed species that managed to eke out an occasional recovery in the experiment was waterhemp, thanks to its famous ability to compensate for plant damage with new branching beneath the point of injury.

And for late-season weeds packed full of seeds, the jolts of electricity from the Weed Zapper reduced weed seed viability dramatically, anywhere from 54% in foxtail to 80% in common ragweed. The most challenging of the weeds tested, waterhemp, saw a 59% drop in seed viability.

Soybeans Take a Yield Hit

In a second round of experiments with the Weed Zapper, Schreier pulled the unit through soybean plants at various growth stages. But this time, the boom was often lowered far enough to catch not only weeds, but also the crop’s top two inches of canopy, meant to simulate accidental crop electrocution that might occur in a farmer’s field.

It wasn’t as fun as frying weeds, Schreier admitted.

“It was kind of painful to do,” she recalled. “I grew up on a farm, so I cringed every time.”

So did the beans.

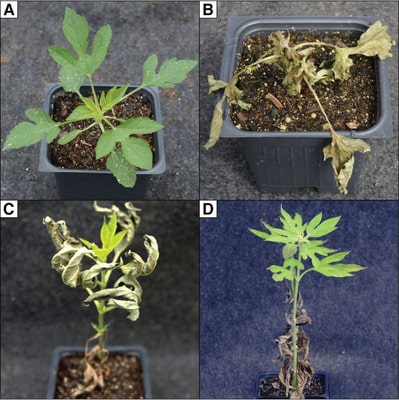

The more mature the plant, the more visible the damage. “Whenever there were pods and seeds present, you could open those pods and see the seed reduced in size,” Schreier explained. Younger soybean plants in vegetative growth stages recovered more visually.

But at almost all growth stages, the researchers confirmed yield loss, ranging from 11% to 26%, with the damage increasing as the plant progressed into reproductive stages.

Schreier said growers can take comfort knowing that the type of damage inflicted on the soybeans was likely a “worst-case scenario” in a row-crop field, since the boom spent approximately 75% of its time maintaining contact with the soybeans deliberately.

“Growers that have a clear height differential between waterhemp and the soybean canopy would not need to maintain contact with the soybean canopy,” the study concludes.

But the Weed Zapper is a potent tool, Schreier cautions interested growers. “Whatever the Zapper is doing to the plant, can also happen to us,” she warned. “The manufacturer says to stay 50 feet away, as long as the PTO is on. And we carried a fire extinguisher with us in case of fires.”

Research Ahead

Bradley’s weed science team at MU is already tackling follow-up questions to the study, with continued funding from the Missouri Soybean Merchandising Council, as well as funding from the North Central Soybean Research Board.

The biggest question is why researchers saw plant recovery in certain species and at certain times, Schreier said. “That’s something we’re looking at now.”

The researchers are also testing whether weed electrocution has any negative effects on soil health. “We’re taking a lot of soil samples to see if it has any effect on microbial communities or earthworm populations,” she explained. They’re also hoping to determine if it has any impact on less desirable members of the soil community, namely soybean cyst nematodes.

Finally, they will dig more into how individual field factors, such as soil moisture and plant moisture, affect weed electrocution’s effects.

“We’re just hoping to see if more data points might lead to more answers,” Schreier said.

To read more about the Missouri team’s work, see the study in Weed Technology here: https://doi.org/10.1017/wet.2022.56

For more information on the University of Missouri’s Weed Science Team’s future work on weed electrocution, stay tuned to their website and follow them on Twitter @ShowMeWeeds.

For more questions on these studies, you can reach Kevin Bradley at bradleyke@missouri.edu and Haylee Schreier at schreierh@missouri.edu.

Article by Emily Unglesbee, GROW; Photos and videos by the University of Missouri Weed Science Team