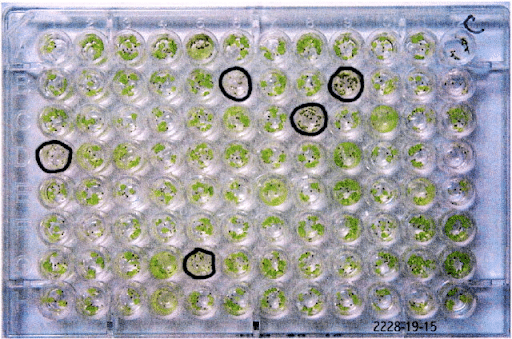

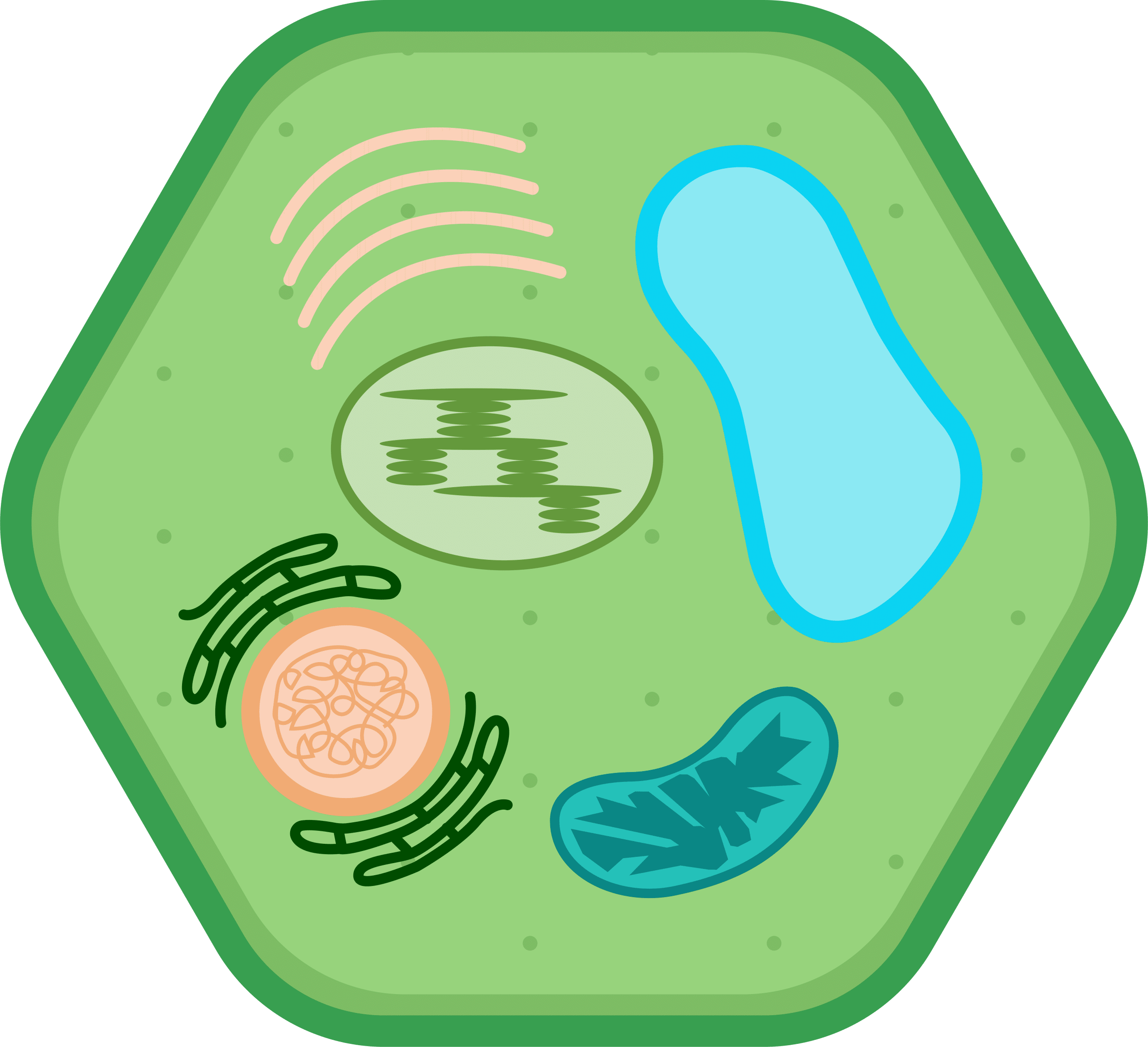

In addition to a change in the structure of the target-site enzyme/protein, another type of target-site resistance is due to increased production of the target-site protein. This occurs when there is an increase in the expression of the target site/protein, or there are increased copies of the gene that codes for the target site/protein (amplification) (Figure 18). These are less common and often associated with low-level resistance (discussed at the end of this section). This type of resistance has been identified most commonly for glyphosate in several weeds including rigid ryegrass, horseweed, and Palmer amaranth.

Figure 18. Another mechanism for target site resistance is an increase in the expression of the target site/protein or in the copies of the gene that codes for the target site/protein (amplification). The plant produces higher amounts of the target-site protein overwhelming the ability of the herbicide to completely disrupt some physiological process. (Image credit: William Curran, Penn State University; Graphic credit: Lourdes Rubione)

Mechanisms of non-target site resistance include:

- Decreased translocation and sequestration

- Reduced foliar uptake

- Enhanced metabolism

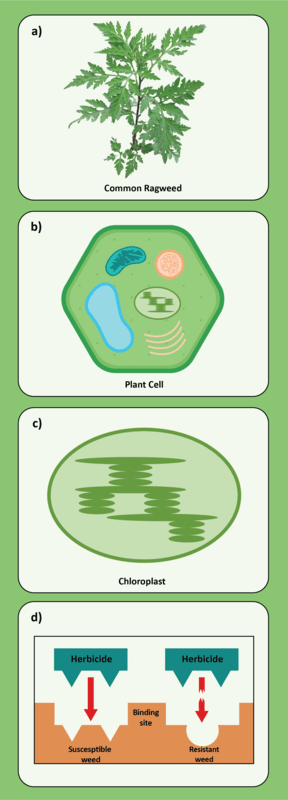

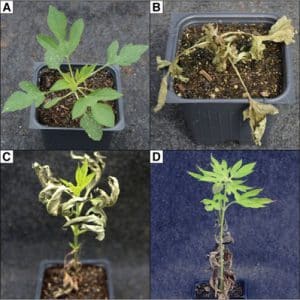

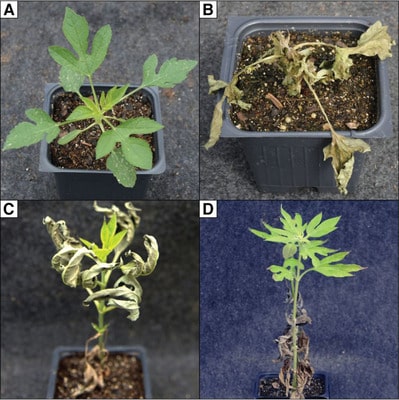

Decreased translocation and sequestration have been reported with several herbicides and weeds. This occurs when less of the herbicide reaches the target site. Some of the best known examples include rigid ryegrass with glyphosate and Italian ryegrass and horseweed with paraquat. Certain populations of giant ragweed evolved the ability to rapidly desiccate treated leaves, trapping the glyphosate and preventing translocation to the site of action. This has been described as the “Phoenix phenomenon” or “Phoenix resistance” (Figure 19).

Reduced foliar uptake or absorption of the herbicide is an uncommon NTSR mechanism that has been reported with several herbicides and weeds including waterhemp with glyphosate and prickly lettuce with 2,4-D. A common suspect is the production of greater amounts of cuticular wax on plant leaves, which could reduce plant uptake, but this mechanism has not always been confirmed.

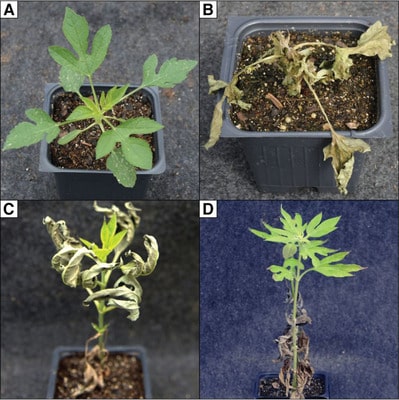

Figure 19. The “Phoenix phenomenon” in giant ragweed treated with glyphosate is shown above. Compare (a) a glyphosate-susceptible plant at 2 days and (b) 21 days after treatment, with (c) a glyphosate-resistant plant at 2 days and (d) 21 days after treatment. With the Phoenix phenomenon, the older leaves desiccate rapidly, trapping the glyphosate in the dead tissue, while the new shoots continue to grow. (Image credit: Van Horn et al. 2018)

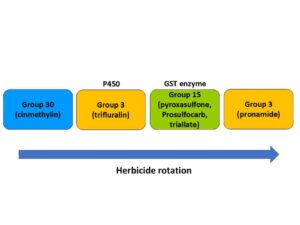

What is enhanced metabolism, or metabolic resistance? Plants have mechanisms to deal with all sorts of potentially harmful compounds in the environment. Herbicides are just one type of compound that some plants have the ability to detoxify. Metabolic resistance is a process within resistant (and tolerant) plants that leads to alteration and inactivation of herbicides.

With metabolic resistance, once the herbicide enters the plant cell, it is altered chemically to form one or more metabolites. Metabolites are often bound to plant structures such as amino acids, proteins, lignin, or sugars to form conjugates. Once bound or conjugated, herbicides are usually rendered immobile, nontoxic, and inactive – unable to do their work in the plant. What is most alarming is the mechanisms for metabolic resistance can be broad-based and cross multiple herbicide modes of action.

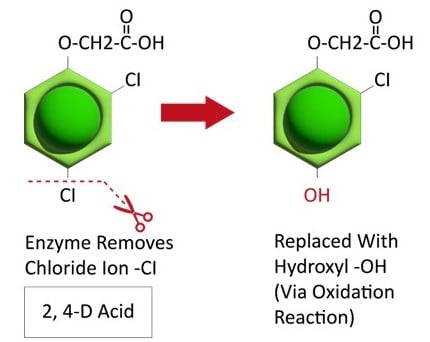

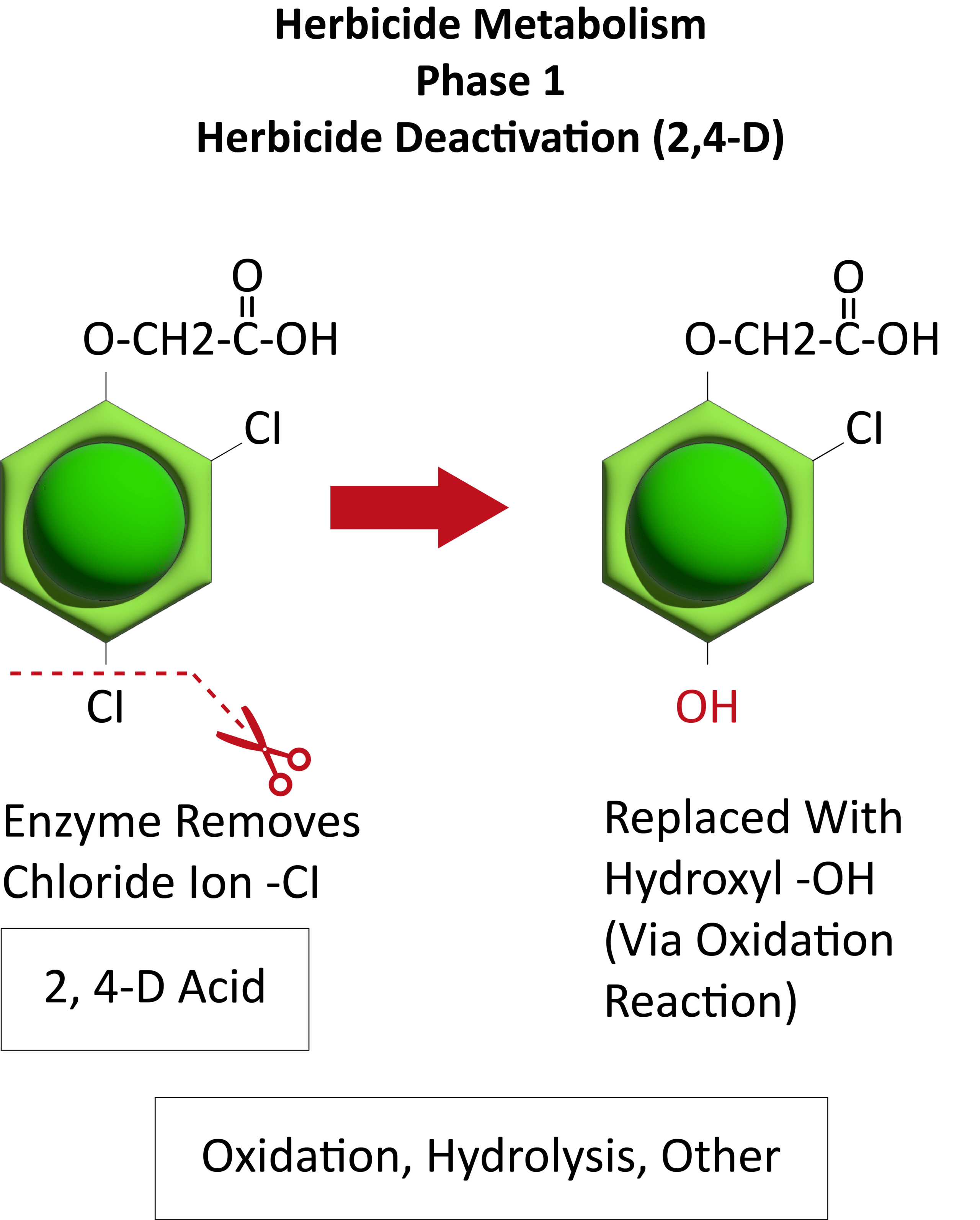

Metabolic resistance is often described in three phases (Figure 20). In the first phase, an enzyme such as Cytochrome P450 removes/cleaves off a sidechain from the herbicide molecule, sometimes inactivating the herbicide. In the example illustration with 2,4-D, a chloride atom is removed and replaced by a hydroxyl group. This is usually an oxidation reaction. In phase two, the hydroxyl group is very reactive and quickly removed and the herbicide molecule joins glucose, or sometimes an amino acid, to form a conjugate. In our example, 2,4-D reacts with glucose. In phase 3, the new conjugate may be transported to a vacuole and stored or may continue to join larger molecules, forming secondary conjugates and eventually helping to build starch or cellulose.

Figure 20. See the three phases of herbicide metabolism, using 2,4-D as an example, above. (Image credit: William Curran; Graphic credit: Lourdes Rubione)

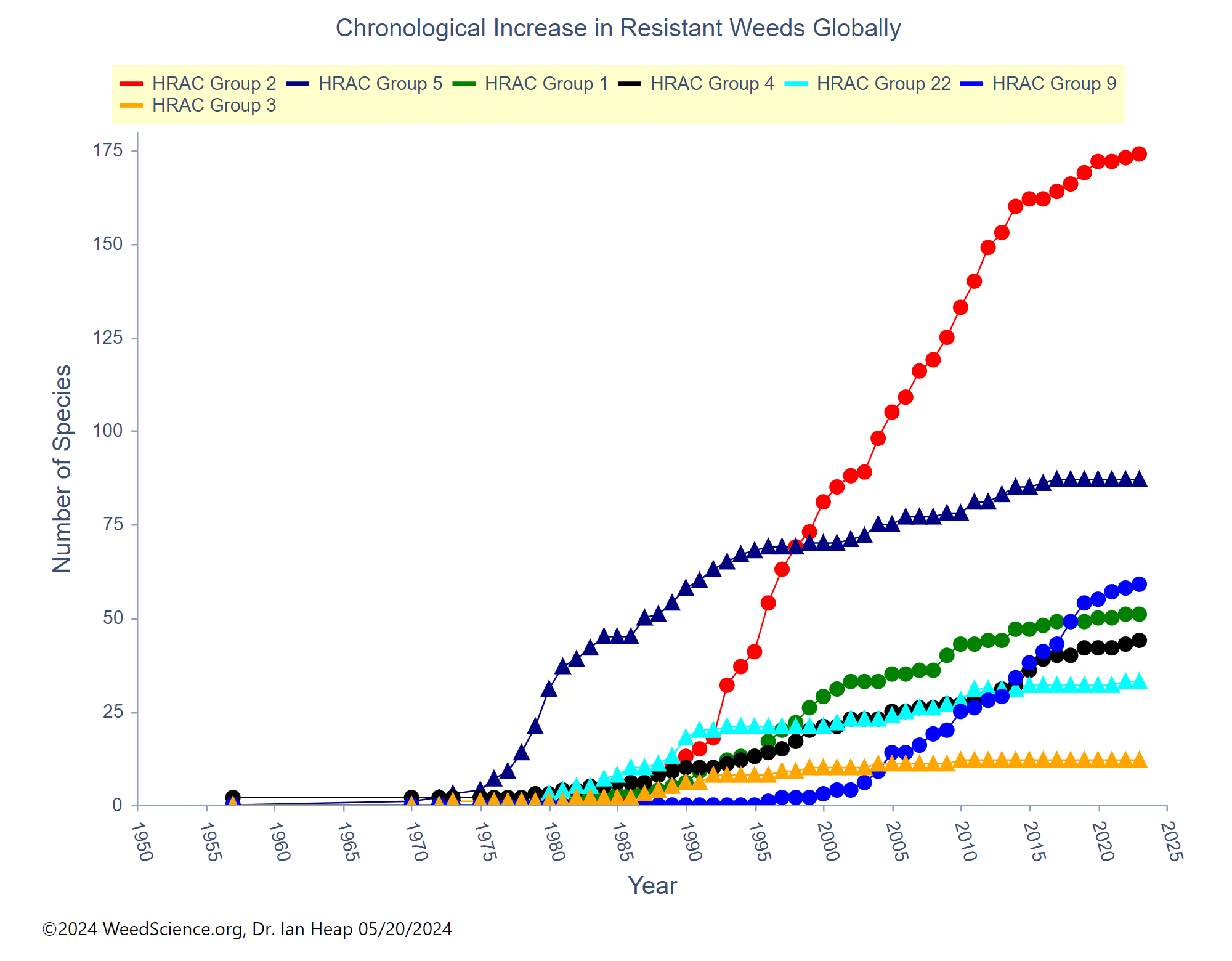

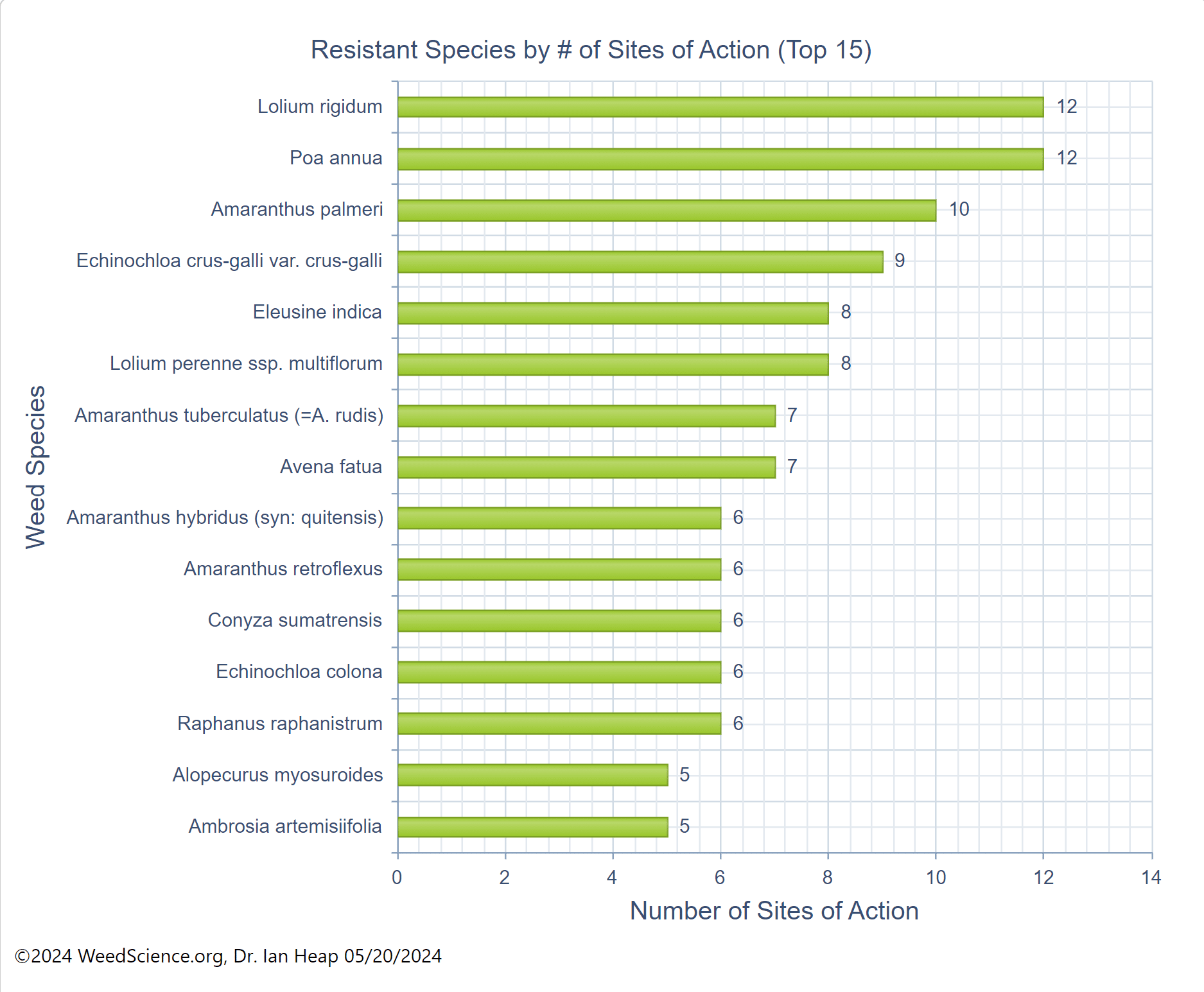

These metabolic processes usually have an impact across a broad range of chemicals and may be capable of inactivating herbicide compounds that the plant has never encountered. Rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum) in Australia and other Lolium species may be the best examples of weeds with both TSR and NTSR and many cases of cross and multiple resistance. A biotype of Lolium rigidum in Australia has evolved resistance to seven different modes of action displaying a variety of mechanisms. Metabolic resistance in Lolium can be responsible for both the resistance to Group 1 and 2 herbicides as well as Groups 5 and 6. Reduced glyphosate translocation in Lolium spp. has also been identified as a NTSR mechanism in a number of countries.

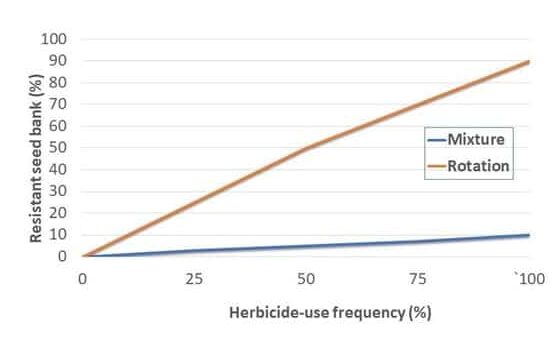

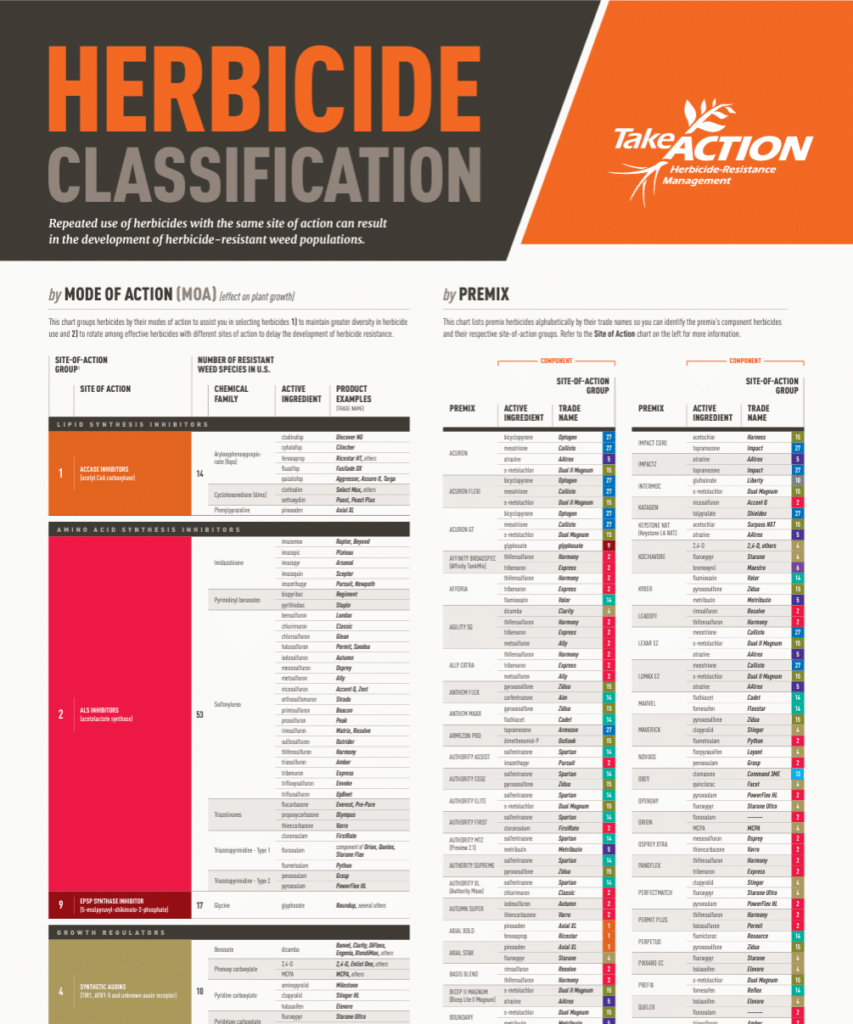

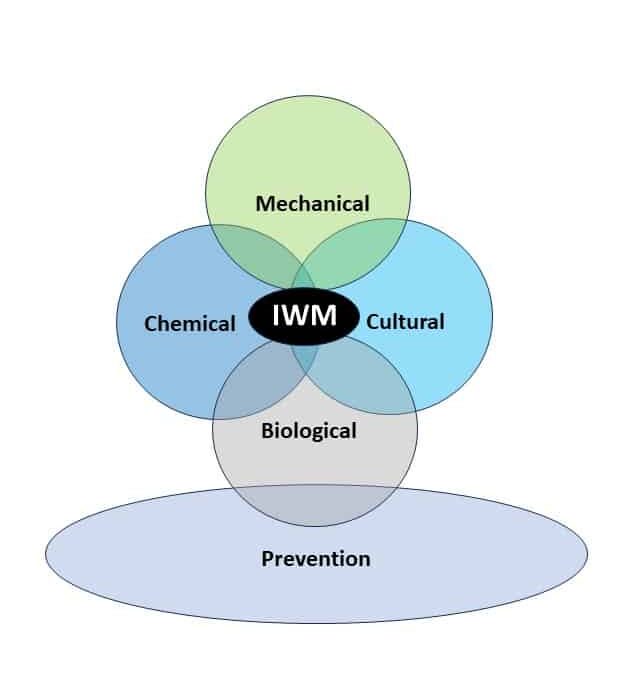

Unlike target-site, metabolic resistance could quickly result in broad cross-resistance, potentially eliminating the effectiveness of herbicides from multiple modes of action. Metabolic resistance is quickly gaining ground with several herbicide groups including 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 14, 15, and 27. Previously recommended herbicide management approaches, such as tank-mixing modes of action or rotating herbicides, are not always effective against metabolic resistance. New approaches must be developed that will require a greater emphasis on non-chemical weed management.

Some herbicides have demonstrated both TSR and NTSR in some weeds. Groups 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, and 14 have shown both TSR and NTSR in some weed species. The herbicide glyphosate (Group 9), one of the most studied cases of resistance, has demonstrated TSR as an altered EPSPS enzyme, as well as amplification of the gene encoding the EPSPS enzyme. NTSR mechanisms for glyphosate include sequestration in the vacuole and enhanced metabolism.

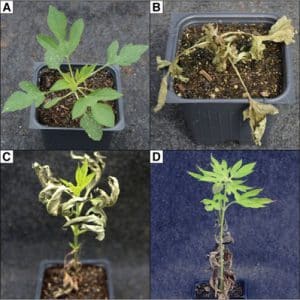

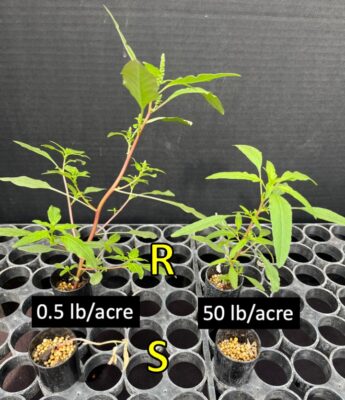

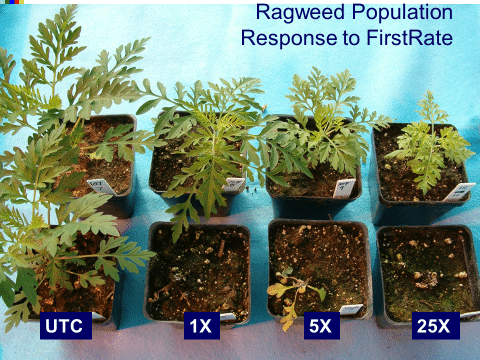

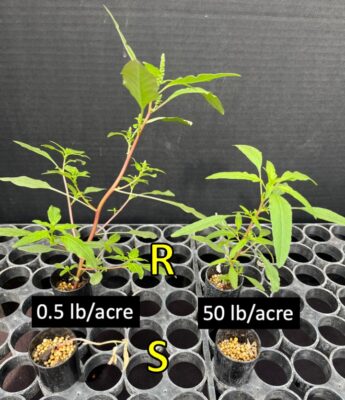

High-level vs. low-level resistance. The response of individual plants can be different based on the herbicide, weed species, and mechanism(s) for resistance. Plants with high-level resistance may tolerate a 100X dose or more of the herbicide (Figure 21). Target-site resistance and a change in the structure of the target protein is usually responsible for high-level resistance. High-level resistance has been identified in Groups 1, 2, and 5.

Low-level resistance may express itself with a range of plant responses, from slight injury to nearly fatal injury. With low-level resistance, a 2X or 3X dose may still kill the resistant biotype. This type of resistance can result from both TSR and NTSR. Low-level resistance is more common in Groups 4, 9, 14, and 22. Historically, low-level resistance has taken longer to detect since it mimics many responses that weeds have when treated with herbicides under less-than-ideal conditions. (See Section 5).

Sidenote: Some of the latest herbicide-resistant crop technologies were actually developed using metabolic resistance. Enlist Corn is a new multiple herbicide-resistant corn trait that confers resistance to 2,4-D, glyphosate, and the Group 1 aryloxyphenoxypropionate herbicide family (FOP herbicides). The resistant corn can metabolize both the Group 4 herbicide 2,4-D and the Group 1 FOP herbicides because of their similar chemical structure. Glyphosate resistance in Enlist corn is based on target-site resistance.

Figure 21. This waterhemp population with high-level resistance to atrazine is able to survive a dose of 50 lb/acre, whereas a normal sensitive population was controlled at 0.5 lb/acre. A typical field use rate of atrazine is 1.5 lb/acre. (Photo credit: Patrick. Tranel, University of Illinois)