Can harvest weed seed control technology actually reduce the vast deposits of weed seeds buried in Midwest soybean fields?

The answer is yes, according to a recently published study from the University of Missouri.

The Mizzou team, led by Extension Weed Scientist Dr. Kevin Bradley, tested a combine attachment called the Seed Terminator. Known as a seed impact mill, the device grinds up chaff residue – and weed seeds – as they leave the combine. Bradley’s team spent two years chasing the machine around five sites in Missouri, catching chaff, straw, weed seeds and facefuls of dust with nets, buckets and plastic trays.

Ultimately they found that the Seed Terminator’s grinding apparatus successfully squashed the vast majority of weed seeds that made it into the combine. These findings, funded by the United Soybean Board and Missouri Soybean Merchandising Council, echo ongoing research on other HWSC units as well, including the Redekop SCU and integrated Harrington Seed Destructor. It’s a promising result for farmers beset by herbicide-resistant weeds.

But will American farmers jump on board with these seed-crushing units, which come with both a learning curve and hefty current price tags ranging from $75,000 to $100,000?

That’s a harder answer that you won’t find in this new study, says Bradley, noting that those costs should fall as market adoption of the technology increases. His team did measure operating costs of the units, but couldn’t speculate much beyond that.

“What our economic analysis doesn’t do is put an exact figure on the value of not having resistant pigweed seed in your soil,” he explains. “So the bottom line is – what value do you place on not returning that resistant seed to the soil each year?”

While that’s hard to pinpoint, it’s sure to be a big number for most row crop growers. One 2017 study suggested that managing glyphosate-resistant weeds alone likely costs American cotton, soybean and corn growers more than $1 billion a year.

To Catch and Destroy a Weed Seed

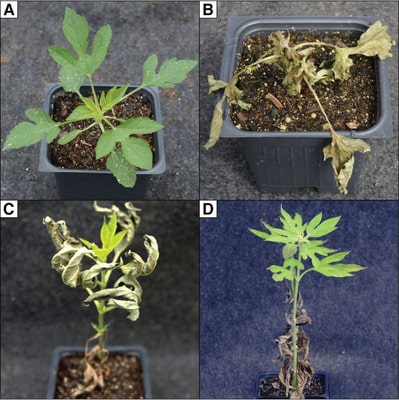

As Bradley and his team discovered, the Seed Terminator is quite good at crushing the life force out of weed seeds that enter it, even those as small as pinpoint-sized waterhemp seeds. They found that, on average, 94% of waterhemp seed leaving the seed impact mill was dead on arrival.

There’s a catch, though – and it’s a big one. Between 22% and 40% of the available waterhemp seed in a field never even made it into the combine and through the mill. Instead, they shattered the moment the combine reel collided with the weeds, raining seeds down onto the ground, safe from the Seed Terminator and into the soil seedbank. A fraction of weed seeds also tends to get lost somewhere in the threshing process, dodging the mill and spitting out the back of the combine with the straw, the researchers found.

Header loss for weed seeds tended to be lower when the weeds had higher moisture levels, Bradley notes. And waterhemp seed clung to its mother plant more effectively than other weed seeds – header loss of velvetleaf was extremely high (89%), with morningglory closer to 52% and lambsquarter dropping about 34% of its seed at the header.

For weed seeds that made it through the combine, however, the Seed Terminator was very effective on all species, averaging 98% destruction of giant foxtail seed, 96.5% of morningglory seed, 97% of lambsquarter seeds and 80% of velvetleaf seed.

Robbing the Seedbank of Deposits

Perhaps the most compelling conclusion of the Mizzou research was the team’s attempt to quantify how the Seed Terminator affected the motherlode – the buried bank of weed seeds, waiting and ready to emerge, year after year.

“That’s ultimately what this whole thing is about – if these impact mills are going to be adopted, it’s because we’re deciding, as an industry, that we need to target the weed seedbank,” Bradley explains. “So we wanted some real data on that.”

After accounting for all weed seeds lost at the header and within the combine, they ran the math. The conclusion: the Seed Terminator resulted in 56% less waterhemp seed returning to the soil compared to a conventional harvest over two years.

“That might not be as big a number as some people want to hear, but as a weed scientist, that’s a tremendous reduction,” Bradley notes.

The team also directly sampled waterhemp seedbanks of some research fields following harvest. They found that it generally took two years to see a significant reduction in the seedbank, but in especially weedy fields, the effect was often notable within a single year. That echoes Australian research, which has found that a wide range of harvest weed seed control systems there reduce rigid ryegrass populations by an average of 60% in the following year.

Operating Cost Breakdown

Finally, the Mizzou team collected and analyzed economic data – namely, how much costlier it was to run the Seed Terminator compared to a conventional harvest. They found that running the Seed Terminator increased their combines’ engine load by 12.5%, with an average increased fuel consumption of about 3 gallons per hour.

Overall, the team concluded that the total operating cost of using the Seed Terminator was roughly $6 per acre higher than a conventional harvest.

That, combined with the $80,000 price tag, and the learning curve that comes with adding a new function to a combine’s complicated threshing process, may be a deterrent to interested farmers, Bradley notes.

“But the main thing I’d emphasize is not to get too blown away by the initial high costs right now, because I think in the future, those will come down,” he adds. “Down the road, more and more manufacturers may just offer this as a checkbox option on their combine sales.”

Text by Emily Unglesbee, GROW. Photos by the University of Missouri Weed Science Team.