You can’t keep a Southern weed down for long.

That’s the takeaway from a recently published meta-analysis of cover crops and weed suppression in Southeastern row crop fields.

Ultimately, researchers found that lush Southern cover crop stands could reliably drop weed emergence and overall populations by 50% in the Southeast. But the weeds that fought their way through the residue? They thrived.

“Essentially, weeds recover from early suppression in the Southeast, due to our higher moisture and heat,” explains Dr. Nicholas Basinger, a weed scientist at the University of Georgia, who was a co-author on the paper. That means farmers are often left with the same weed biomass and seed production at the end of the season, despite reduced weed populations.

The Southeastern paper was inspired by an earlier meta-analysis of cover crops and weeds in the Midwest, led by Dr. Virginia Nichols at Iowa State University in 2020. There, researchers found that cover crops didn’t ultimately affect final weed populations in a field, but heavy residue could reliably shrink final weed biomass (size) by 75%. Without the benefit of sweltering Southern summers, it would appear those Midwestern weed escapes couldn’t reach their full potential after fighting through cover crop residue.

That doesn’t mean Southeastern growers shouldn’t also embrace cover crops for weed management, the Southeastern researchers caution – it just means they must add other weed control strategies to the mix, to keep those aggressive Southern weeds at bay.

The Southern Weed Lifestyle

The Southeastern meta-analysis was led by weed scientist Dr. David Weisberger, during his Ph.D. work at the University of Georgia, after he had assisted on the earlier Midwestern meta-analysis.

He dug into nearly 60 studies of cover crop use in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. He found that, unlike Midwestern producers up north, who often struggled to grow enough cover crop biomass, farmers in the Southeast could reliably grow huge cover crop stands.

“In the Southeast, everything grows more, and that means EVERYTHING.

Dr. David Weisberger

Cover crops and weeds.”

But their weed suppressive abilities were somewhat muted – a nearly 6,000 lb/acre cover crop stand was associated with only a 50% drop in weed densities, and no change in final biomass. In contrast, the Midwestern analysis found that 4,500 lbs/acre of cover crop biomass could fairly reliably suppress weed biomass by 75%.

It all comes down to plentiful rain and those long Southern summers, says Weisberger, who is now a research associate at the University of Rhode Island. “In the Southeast, everything grows more, and that means EVERYTHING,” he says. “Cover crops and weeds.”

The same conditions that allow for large, fast-growing covers also shorten the lifespan of certain cover crop residues, such as legumes.

“We can produce a lot of biomass, but it doesn’t last as long, because the climate is warm and wet,” explains Basinger. “By the time cotton plants are a foot high, [sometimes] there’s no cover crop residue left – it just melts away.”

Primarily, however, the weeds that do sneak through quickly take advantage of their roomier conditions and ample heat units.

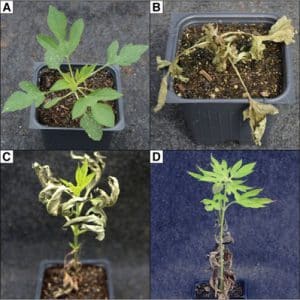

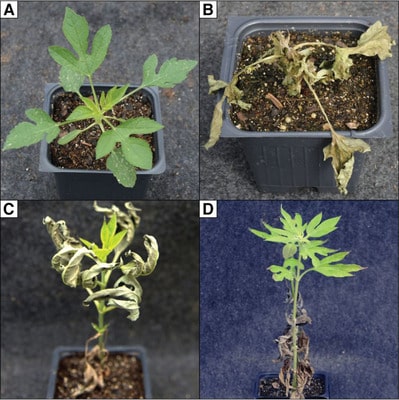

“The ones that survive can get just incredibly huge,” says Basinger.

And with that size comes impressive seed production. In a separate, but related field study, Weisberger measured Palmer amaranth plants grown in different cover crop treatments compared to bare ground plots. He found that even though the covers greatly reduced Palmer emergence compared to a bare ground plot, the plots ended up with the same seed production.

The pigweeds simply adjusted to their resources, with a lone Palmer escape gobbling up all the available light, moisture and nutrients and then producing as much seed as 10 pigweeds crowded into a similar space.

Or, as Basinger puts it: “That one surviving weed can really screw you up.”

Cover Crops: A Tool Among Many

So should Southeastern farmers not bother with cover crops? Not at all, Weisberger and Basinger insist.

First, a 50% reduction in the number of weeds in a field is nothing to sniff at. “It’s not 100%, but it provides a good buffer and gives farmers more time to get herbicides out there, particularly in the spring,” Weisberger notes.

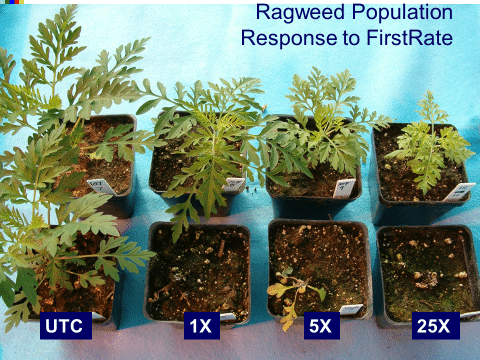

Moreover, lower weed densities are an important tool in the fight against herbicide resistance.

“Having fewer emerged weed seedlings at the time of an initial post-emergent herbicide application means the likelihood of selecting for a resistant individual or individuals is reduced,” Weisberger explains. “This is essential in maintaining the efficacy of the chemistries we have and is a critically important part of an IWM approach.”

Just be sure to account for the reduced ability of cover crops to knock back weed biomass and seed production, by overlapping other weed control tactics, he adds.

“Cover crops can be a really positive addition, but they need to be augmented with overlapping residual herbicides and other non-chemical tactics, like harvest weed seed control,” Weisberger concludes.

For more information on using cover crops for weed control, see this GROW webpage. For more news articles on cover crops and weed management, see the GROW News Page.

Text by Emily Unglesbee, GROW; feature and header photo by Nick Basinger, UGA