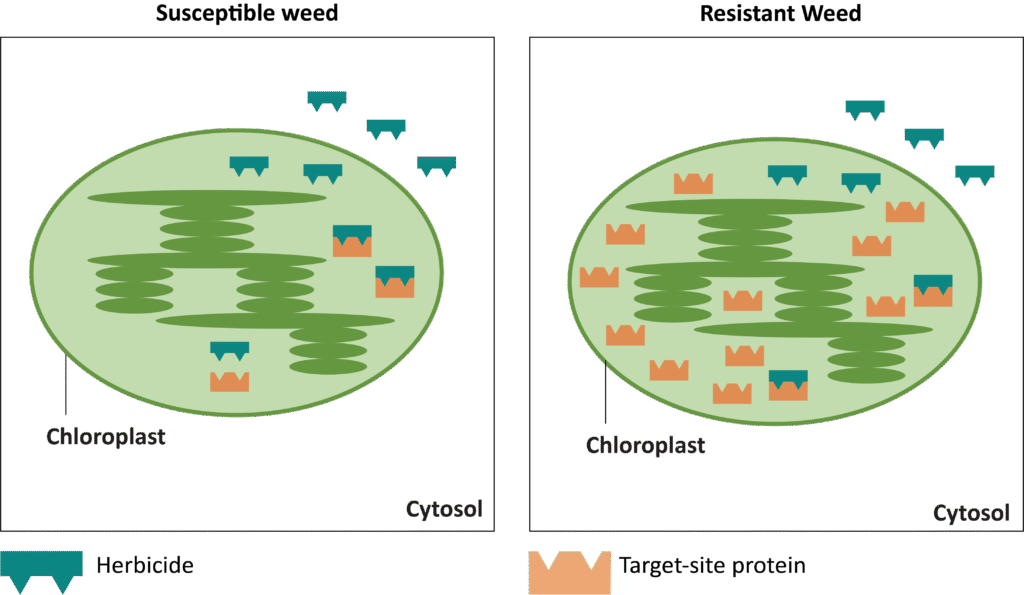

By the time North Carolina farmers noticed that their Italian ryegrass wasn’t responding to paraquat in October of 2020, it had already taken over. Italian ryegrass’ reign of terror as a herbicide-resistant weed in the U.S. began in the 1990s with ACCase-inhibiting herbicides (Group 1). The recent confirmation of paraquat-resistant ryegrass also led to the discovery of Italian ryegrass biotypes with multiple resistances to as many as four different herbicide groups (Groups 1, 2, 9, and 22). This sprawling web of resistant ryegrass has left many farmers across the United States with just fall-applied residual herbicides and integrated weed management to manage this weed.

“[Farmers] were abandoning fields of corn, just walking away from them because they couldn’t control the ryegrass,” North Carolina State University (NCSU) Extension weed specialist, Dr. Charlie Cahoon explains.

That bleak reality drove Cahoon and his team to research the best cover crop and residual herbicide combination for farmers to combat Italian ryegrass, also known as annual ryegrass. His two-year study found that combining large-biomass-producing cover crops with residual herbicides they can tolerate, such as pyroxasulfone or S-metolachlor, will suppress Italian ryegrass and its seed production. But farmers will need to avoid using either method alone, as using these two methods together covers all weed-smothering bases.

Friend Turned Foe

Italian ryegrass hasn’t always been a dreaded sight in fields. It was once (and still is, in some areas) a popular erosion-preventing cover crop for farmers in the United States, according to Cahoon. The soil types and climate of North Carolina’s Southern Piedmont region is particularly well-suited for Italian ryegrass.

That made the region especially susceptible to a hostile takeover, as multiple herbicide-resistant ryegrass populations have emerged.

“If you ever find yourself in [North Carolina], you’ll see what looks like fields and fields of just Italian ryegrass,” Cahoon shares.

Cover Crops and Residual Herbicides, A Powerful Duo

It might be tempting to use a fall-applied residual herbicide alone for Italian ryegrass control. After all, managing cover crops can get pricey. But residual herbicides can only squash Italian ryegrass early in the season. Late-season Italian ryegrass control with residual herbicides was nearly nonexistent, Cahoon found.

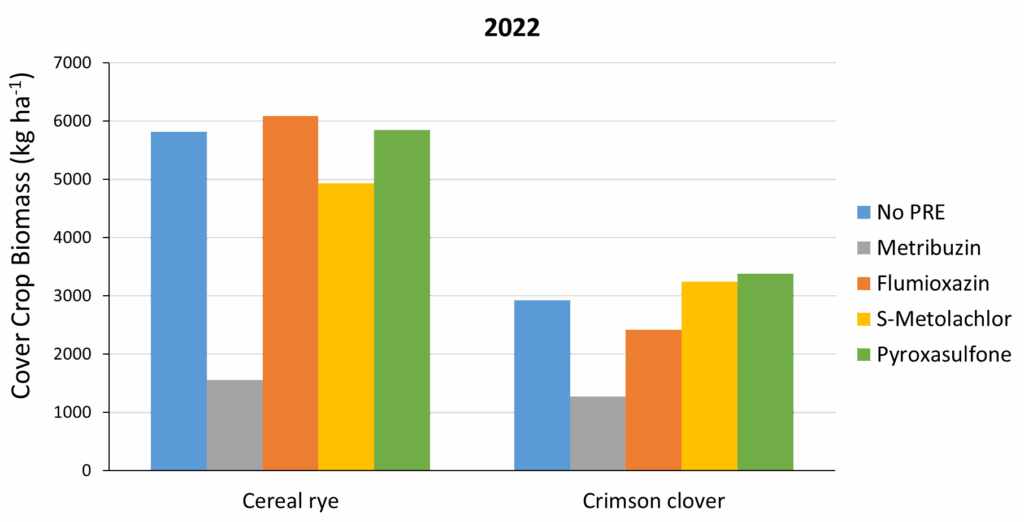

Similarly, it might sound like a good idea to only use a cover crop and skip the residual herbicide altogether. Cereal rye was just as effective as residual herbicides when it produced over 4,400 pounds per acre of biomass, the NCSU researchers found. But there’s always a chance that your cover crop might underperform. In those cases, a residual herbicide is critical to help cereal rye control weeds.

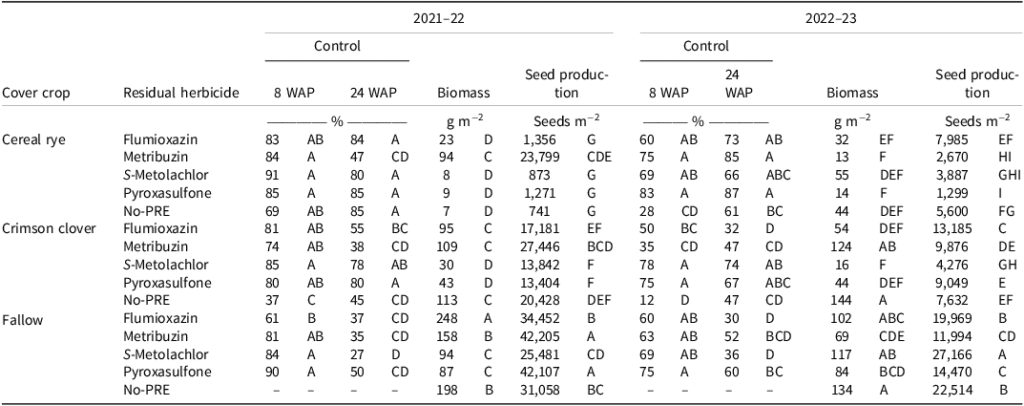

That’s why Cahoon examined how cereal rye, crimson clover, and a no-cover-crop control plot interacted with the use of four residual herbicides: flumioxazin, metribuzin, pyroxasulfone, and S-metolachlor.

Cereal rye and residual herbicides controlled anywhere from 83% to 92% of Italian ryegrass plants eight weeks after planting at one study site. Twenty-four weeks after planting at that same site, cereal rye alone resulted in 85% control and cereal rye paired with residual herbicides resulted in 80 to 85% control.

Combining crimson clover and residual herbicides resulted in 74% to 81% Italian ryegrass control eight weeks after planting at one study site. Crimson clover never reached that 4,400 pound per acre biomass threshold, but it came close with 4,138 pounds per acre.

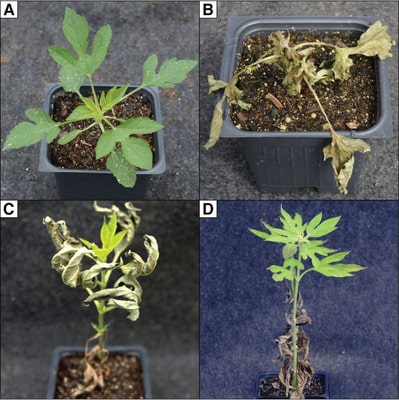

Farmers need to keep one notable consideration in mind when combining cover crops and residual herbicides: Some residual herbicides can punish the cover crops as much as they do the weeds.

Metribuzin severely injured 65% of cereal rye in one study year, and crimson clover was severely injured by both metribuzin and flumioxazin. Injured and stressed cover crops produce less biomass, which tanks weed suppression. Pyroxasulfone and S-metolachlor, though, caused less than 12% injury across cereal rye and crimson clover.

Running on the (Seed) Banks

Controlling Italian ryegrass plants with cover crops and residual herbicides also controls ryegrass seed production, Cahoon found.

Italian ryegrass suffered a 98% seed reduction following the cereal rye and residual herbicide combo. Ryegrass weed seeds have a brief two-year lifespan in the soil seedbank. Cahoon’s research suggests that controlling your Italian ryegrass population could also result in a weed seedbank reduction in just a few years.

“Folks need to get serious about not letting their Italian ryegrass go to seed,” Cahoon says.

“The best way to manage multiple-resistant ryegrass is to never let it on the farm,” Cahoon recommends. But be sure to combine a high-biomass cover crop such as cereal rye with a cover-crop-friendly residual herbicide to stop this grass in its tracks if it does wander into your fields.

“Herbicide-resistant Italian ryegrass is spreading across the state,” Cahoon concludes. “You need to be doing some of these integrated weed management tactics to get ahead of it, or you’re going to end up in the same position as the farmers forced to use cover crops and fall residual herbicides.”

Explore GROW’s website for more information on herbicide-resistant Italian ryegrass, cover crop management, and managing herbicide resistance with integrated weed management.

Article by Amy Sullivan, GROW; Header photo by Charles Cahoon, North Carolina State University; Feature photo by Claudio Rubione, GROW.