Digitaria sanguinalis (L.) Scop.

Also known as: hairy crabgrass, hairy finger-grass, Polish millet, crop grass

Large crabgrass (crabgrass) is a grass weed originally from Eurasia but now widespread across the United States. It is a major problem in row crops (corn, soybean, cotton, wheat), rice, vegetables, turfgrass, and lawns. Crabgrass is highly competitive and reduces crop yield by capturing light, water, and nutrients early in the season. It also exhibits allelopathic effects, which means it releases chemical compounds that suppress crops and other plants near it.

Identifying Features

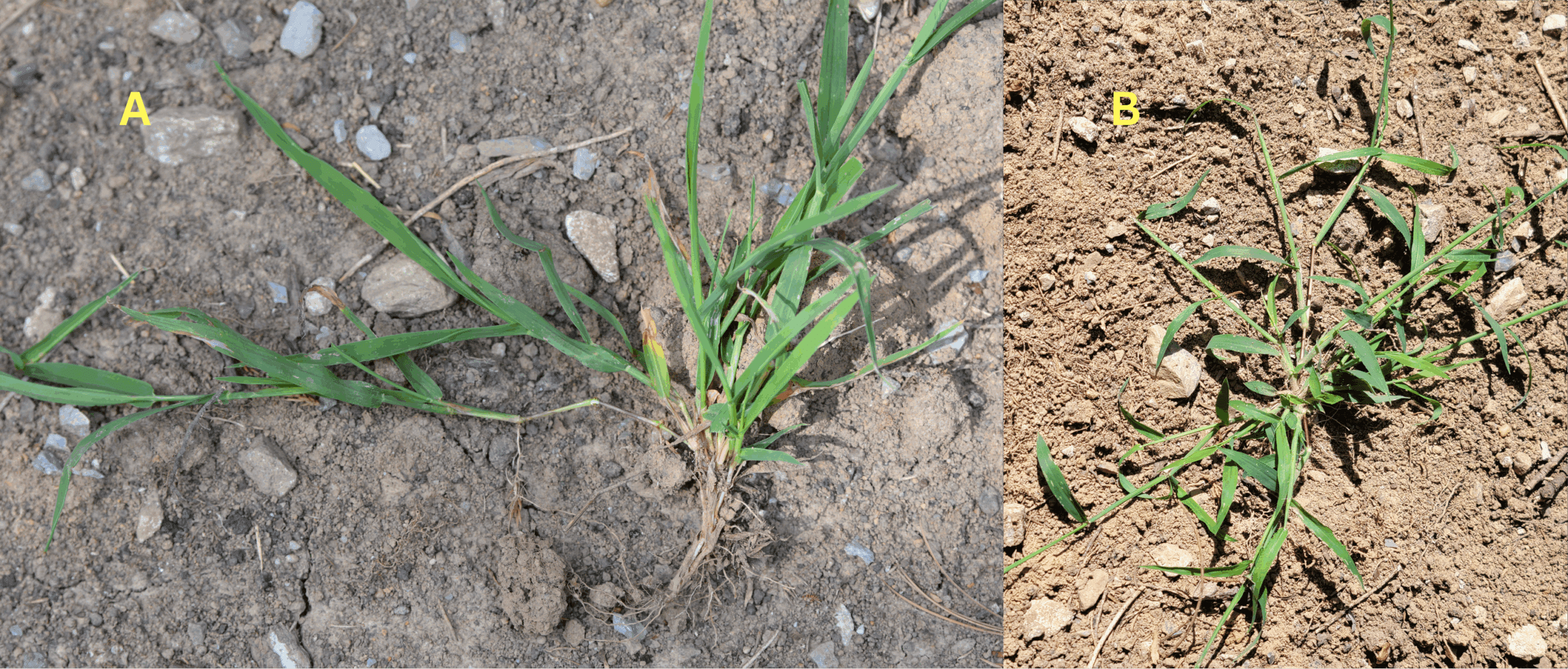

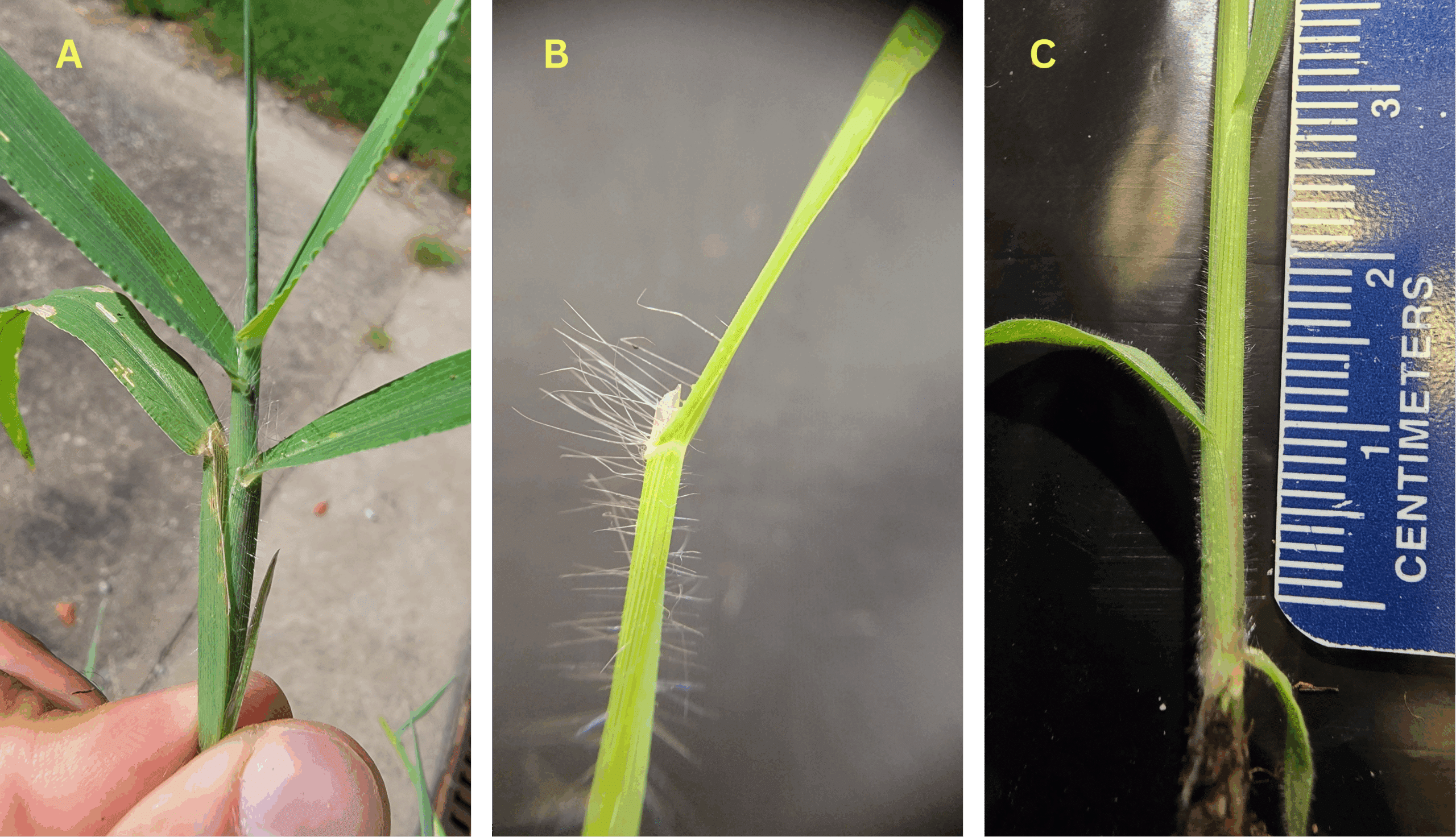

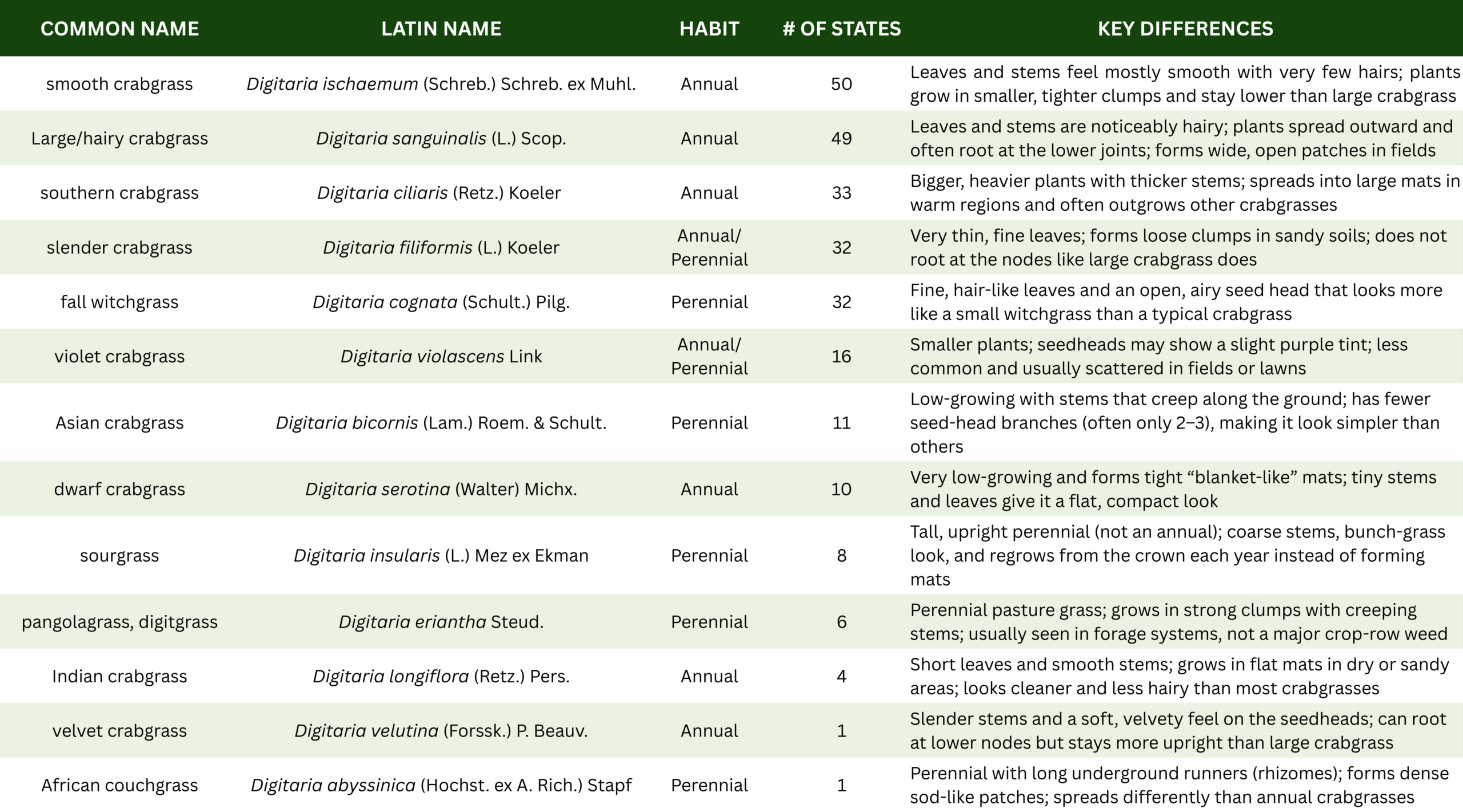

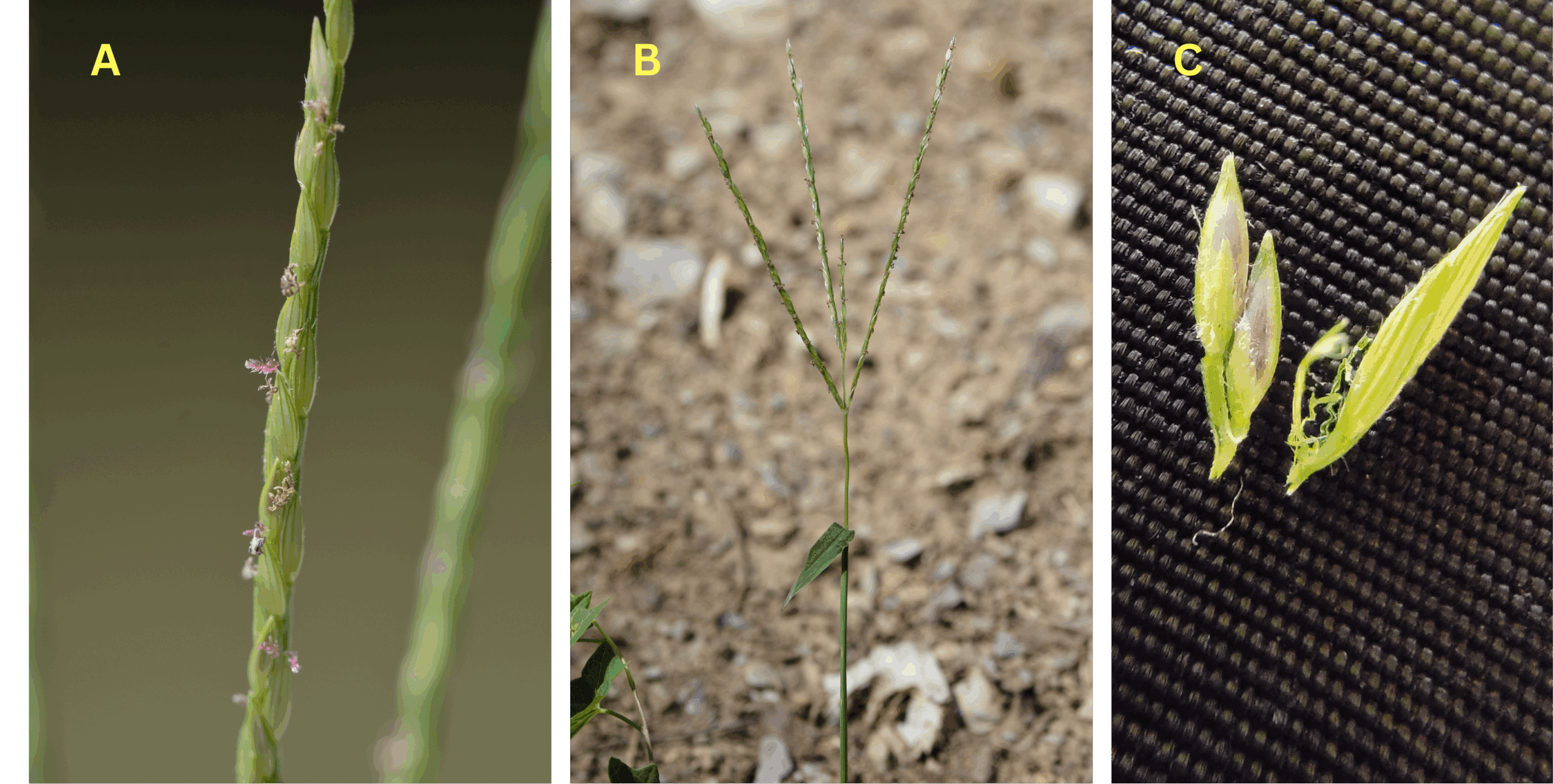

Large crabgrass is a summer annual that begins germinating once soil temperatures reach about 55 °F and continues to emerge in multiple flushes throughout the season. The plants form low, spreading mats with stems that often root at the lower nodes, giving the species its fast, aggressive growth habit. Leaves are flat, narrow, and typically hairy, and the plant produces several finger-like seed heads, usually three to ten, each lined with paired spikelets during mid- to late-summer. Because several Digitaria species occur in the United States, key features that distinguish large crabgrass from look-alikes such as smooth or southern crabgrass are summarized in Table 1, with large crabgrass characterized mainly by its dense leaf hairiness and node-rooting growth form.

Seed Production

Crabgrass is an aggressive grower, setting anywhere from 150 to 700 tillers per plant, and an individual plant’s seed production (which can reach 150,000 seeds over the course of a season) starts soon after it flowers in mid- to late summer. Because new flushes of plants occur throughout the season, seed drop can continue for weeks, but the earliest plants to establish usually contribute the most seed to the soil. Most seeds end up in the top 2 inches of soil, where they can easily sprout. Seed persistence is generally short: about 55% of buried seed survived one year, and none survived beyond three years in a burial study under turf; in contrast, when seed remained on the soil surface in no-till conditions, more than 95% germinated or died within 9 months. This steady buildup of seeds in the soil is a big reason why crabgrass is so tough to control.

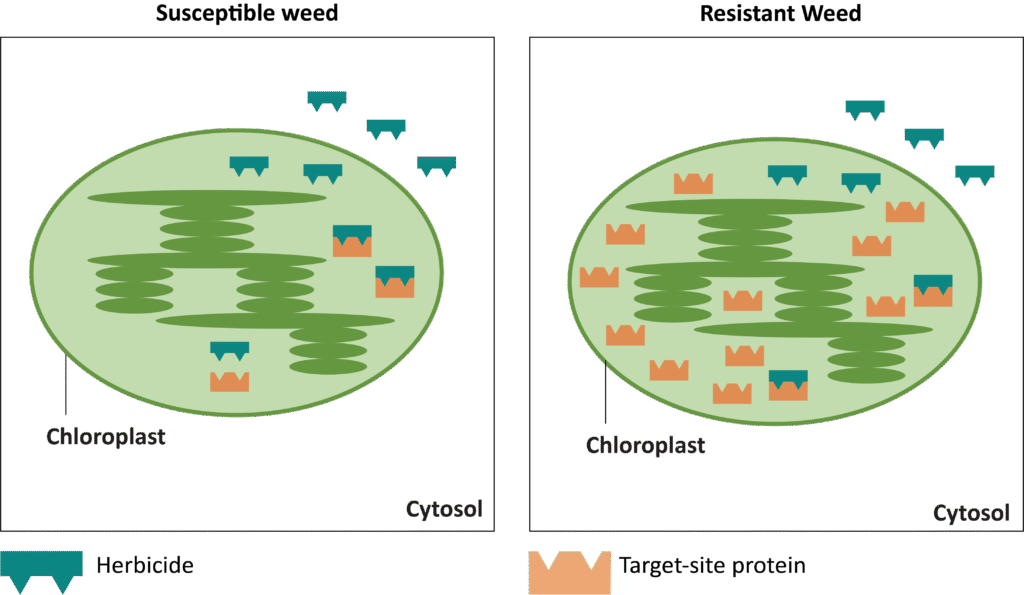

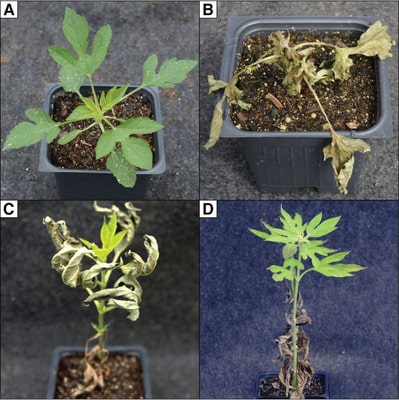

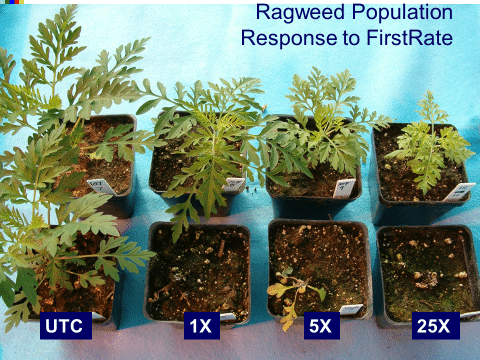

Herbicide Resistance

Crabgrass has confirmed cases of resistance to (Group 1 herbicides) in Wisconsin (in carrots and onions) as well as in Georgia (in turfgrass).

Integrated Weed Management Options

Cover Crops

By shading the soil surface and limiting light penetration, stem and leaf materials from dense cover crops can inhibit crabgrass germination and establishment, though the effectiveness varies depending on the cover crop species, amount of cover crop biomass, and time of year. Consider cover crops that are fast-growing and generate significant biomass, such as cereal rye, when aiming to compete with crabgrass.

Harvest Weed Seed Control

Large crabgrass has some characteristics that make it a good target for harvest weed seed control, including an annual lifecycle, high seed production, and relatively short-lived (mostly less than three years) seed. However, large crabgrass loses about half of its seed prior to soybean harvest, reducing potential effectiveness of harvest weed seed control. Seeds are produced relatively close to the ground, so capturing the seeds with the combine header is also challenging in certain crops.

Crop Rotation

Compared to wide-row systems like corn and cotton, rotating crops that achieve rapid canopy closure, like soybean or small grains, decreases crabgrass competitiveness. Perennial crops that actively compete during large crabgrass’ emergence and growing season can also aid in managing this weed.

Tillage

While shallow tillage or no-till encourages higher densities of seeds close to the surface, deep tillage can hinder emergence by burying seeds below their ideal germination depth (>2 inches).

Predictive Tools

Simple field indicators, such as the spring blooming of forsythia bushes, can be used by farmers as a consistent indicator of when to apply pre-emergence herbicides to prevent crabgrass from sprouting.

Herbicide Control Options

Crabgrass germinates in waves once soils warm, so effective control almost always requires:

- A residual (PRE) herbicide at or before planting to catch the first flushes; and

- A timely POST herbicide on small plants (≤2–3 leaves) to control plants missed by the preemergence herbicide.

Rotating and layering different herbicide modes of action slows herbicide resistance development and improves consistency across weather and soils. See state crop guides for exact products, rates, and restrictions.

Multiple U.S. populations of crabgrass are resistant to Group 1 (ACCase) grass herbicides, with cross-resistance across the FOPs and DIMs (sethoxydim, fluazifop, fenoxaprop, etc.); always diversify modes of action and avoid repeat solo use of the same POST grass killer.

Resources & Citations

A Manual of Weeds. Botanical Gazette 1915, 59, 257–257, doi:10.1086/331531.

Aulakh, J.S.; Hiskes, R.T. The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. 2025, pp. 1–3.

Breeden, G.K.; Brosnan, J.T. Crabgrass Species Control in Turfgrass (W146); 2019;

Cardina, J.; Herms, C.P.; Herms, D.A. Phenological Indicators for Emergence of Large and Smooth Crabgrass (Digitaria Sanguinalis and D. Ischaemum). Weed Technol. 2011, 25, 141–150, doi:10.1614/wt-d-10-00034.1.

Chism, W.J.; Bingham, S.W. Postemergence Control of Large Crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis) with Herbicides. Weed Sci 1991, 39, 62–66, doi:10.1017/S004317450005788X.

Digitaria Sanguinalis (Hairy Crabgrass): Minnesota Wildflowers Available online: https://www.minnesotawildflowers.info/grass-sedge-rush/hairy-crabgrass (accessed on 23 August 2025).

Egley, G. H., and J. M. Chandler. 1978. Germination and viability of weed seeds after 2.5 years in a 50-year buried seed study. Weed Science 26:230-239.

Heap, I. The International Herbicide-Resistant Weed Database. Online Available online: https://www.weedscience.org (accessed on 23 August 2025).

Hoyle, J.A.; Scott McElroy, J.; Guertal, E.A. Soil Texture and Planting Depth Affect Large Crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis), Virginia Buttonweed (Diodia virginiana), and Cock’s-Comb Kyllinga (Kyllinga squamulata) Emergence. HortScience 2013, 48, 633–636, doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.48.5.633.

Kansas State University. (2025). Chemical weed control for field crops, pastures, rangeland, and noncropland (SRP 1190). Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service.

Large Crabgrass – Digitaria sanguinalis – Plant & Pest Diagnostics Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/large-crabgrass-digitaria-sanguinalis/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 23 August 2025).

Louisiana State University AgCenter. (2025). Rice weed control guidelines. LSU AgCenter.

Masin, R., M. C. Zuin, S. Otto and G. Zanin. 2006. Seed longevity and dormancy of four summer annual grass weeds in turf. Weed Research 46:362-370.

Oreja, F.H.; Stempels, M.; de la Fuente, E.B. Population Dynamics of Digitaria sanguinalis and Effects on Soybean Crop under Different Glyphosate Application Timings. Grasses 2023, Vol. 2, Pages 12-22 2023, 2, 12–22, doi:10.3390/GRASSES2010002.

Oreja, F.H.; Vega, A.S.; Jones, E.; de la Fuente, E.B. Biology, Ecology, Distribution and Management of Large Crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis). Weed Res 2025, 65.

Purdue University, Ohio State University, University of Illinois, & Michigan State University. (2025). Weed control guide for Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan. Extension Bulletin.

The Cultural History of Plants – 1st Edition – Sir Ghillean Prance – M; Prance, S.G., Nesbitt, M., Eds.; 1st Edition.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2005; ISBN 9780415927468.

Wang, R.; Sun, Y.; Lan, Y.; Wei, S.; Huang, H.; Li, X.; Huang, Z. ALS Gene Overexpression and Enhanced Metabolism Conferring Digitaria sanguinalis Resistance to Nicosulfuron in China. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1290600, doi:10.3389/FPLS.2023.1290600/BIBTEX.

Zhou, B.; Kong, C.H.; Li, Y.H.; Wang, P.; Xu, X.H. Crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis) Allelochemicals That Interfere with Crop Growth and the Soil Microbial Community. J Agric Food Chem 2013, 61, 5310–5317, doi:10.1021/JF401605G

Author

Sirwan Babaei, Southern Illinois University–Carbondale

Editors

Emily Unglesbee, GROW

Karla Gage, Southern Illinois University-Carbondale

Mark VanGessel, University of Delaware

Michael Flessner, Virginia Tech

William Curran, Penn State (emeritus)