Many reports have circulated the US concerning widespread dicamba injury to off-target crops, particularly in the Mid-South and Midwest. According to a national survey led by Kevin Bradley, weed scientist at the University of Missouri, 3.1 million acres of crops were reported injured by dicamba in 2017, which was legally applied to dicamba-resistant soybeans for the first time this year.

According to weed specialists at the University of Minnesota, this issue is concerning for several reasons beyond injury to crops. These include neighbor disputes about drift, pressure to purchase dicamba-resistant beans as a defensive tactic, and the complicated dicamba label and associated regulations. We have also seen misleading manufacturer claims that dicamba-related technology is the stand-alone solution for herbicide resistant weeds. There is no silver bullet for herbicide resistant weeds.

If growers come to over-rely on dicamba products, history suggests that the cycle of resistance will continue, and we will face increased weed resistance to dicamba as we have with glyphosate, triazine, and ALS-inhibitor herbicides. It is important to remember that there is still no silver bullet for resistant weeds, and dicamba is no exception.

Over the winter months, farmers, extension educators, crop consultants, industry and government officials will discuss how to approach this issue for next year. Dicamba application to dicamba-tolerant soybeans will remain an option in most states; the EPA recently announced added regulations to be applied in 2018 for continued use of this product. It is predicted that many farmers will continue to plant dicamba-resistant soybeans and apply dicamba. Some may be applying it as a direct tactic to target herbicide-resistant pigweed in their fields. In order to ensure sensible use of dicamba and slow the development of weed resistance to it, it is important that we recognize how we got to this point: the development of highly competitive weeds that are resistant to multiple groups of herbicides.

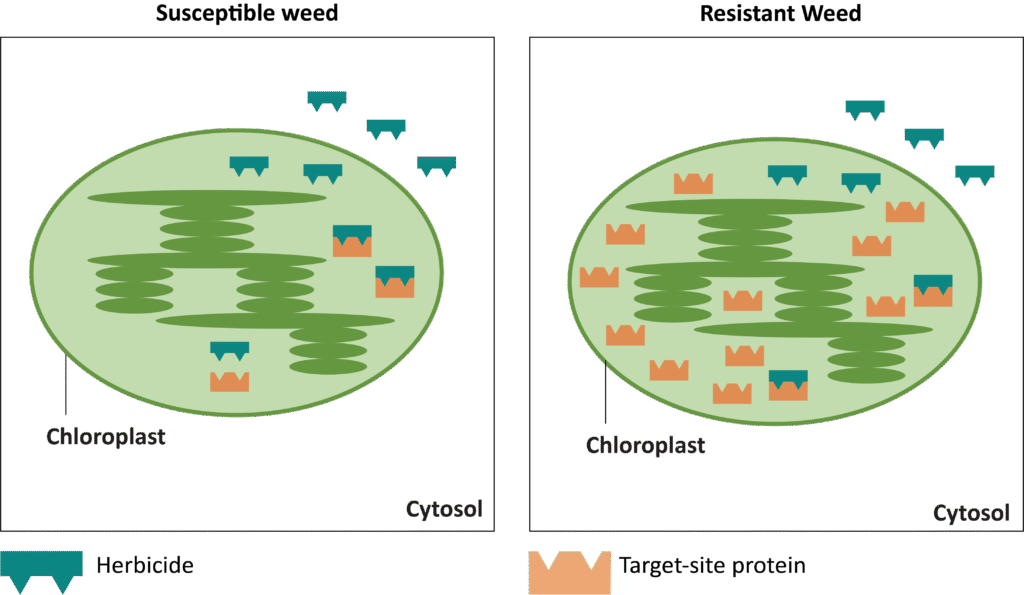

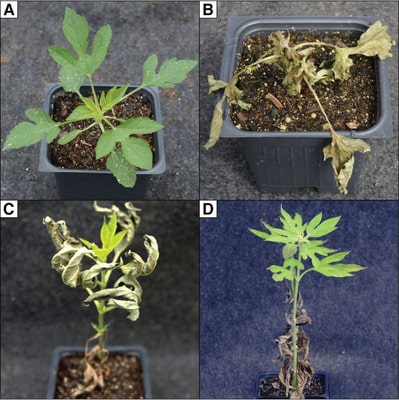

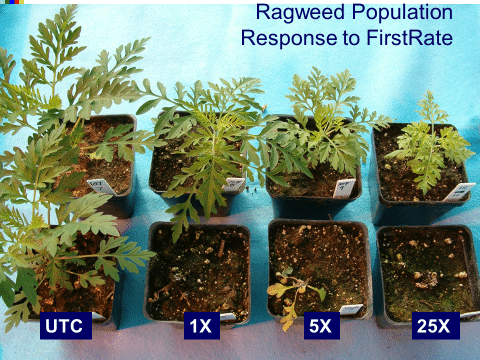

Over about the past two decades, farmers have had to deal with increasing numbers of resistant weeds, particularly weeds that are resistant to multiple popular herbicide groups. Some of the most challenging examples include multiple-resistant tall waterhemp, Palmer amaranth, giant and common ragweed, and kochia. Unfortunately, heavy use of triazines and ALS-inhibitor herbicides led to the selection of triazine- and ALS-resistant weeds. When glyphosate-resistant crops became available two decades ago, glyphosate use increased as it became a popular and effective tool for stubborn and resistant weeds. But weeds soon responded by developing resistance to it as well. Currently, farmers in states like Arkansas and Missouri are turning to dicamba as a solution to widespread Palmer amaranth that is resistant to multiple herbicide groups, including glyphosate and ALS-inhibitors. While dicamba products are often effective on Palmer amaranth, it is not a silver bullet for herbicide resistant weeds. If it is overused, weed populations will likely adopt resistance against it rapidly, including Palmer amaranth, continuing the treadmill of resistance that we have seen with popular herbicides over the past 25+ years.

Unfortunately, if the treadmill continues with dicamba, we will run short on remaining effective chemistries against weeds like Palmer amaranth sooner rather than later. We do not know of any new herbicide modes of action on the horizon, so conserving current effective technologies is very important.

In order to conserve effective chemistries, farmers should diversify the herbicide modes of action that they are applying within each season and between seasons. Avoid overreliance on one or a two modes of action. By diversifying the number of effective herbicide MOA in a tank and from one application to the next, the producer is limiting the opportunities for weeds to develop resistance. Modes of action can and should be diversified several ways: In tank mixes, between applications within a season, and rotated between seasons. Rotating crops helps facilitate the rotation of herbicide MOA. Additionally, it is important to use the full rate of each herbicide according to the label, as incomplete control can also lead to the development of resistance.

Integrate other cultural and mechanical practices alongside herbicide control in order to reduce the introduction of new weeds, reduce the weed pressure that is put on herbicides, and to target stubborn weeds from multiple angles.

For more information on the development and spread of herbicide resistant weeds: The Basics of Herbicide Resistance

For more information on diversifying modes of action: Herbicide Control page

To find a list of herbicide resistant weeds in your state: Search by State

Article by GROW staff