Listen to this article above!

Tired of mucking through flooded rice paddies to control escaped weeds? Another weed-control strategy might be on the horizon, as Texas A&M researchers collaborating with the USDA-ARS showed that targeted spray drones could become the next big thing in rice weed management. This strategy can help keep weed escapes from replenishing your field’s weed seedbanks.

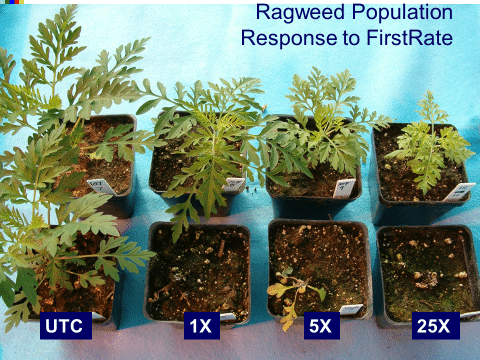

Targeted spray drones that used computer vision for weed detection successfully controlled anywhere from 62% to 95% of weed escapes in rice fields in the study led by Texas A&M grad student Bholuram Gurjar, Dr. Muthukumar Bagavathiannan, and USDA-ARS researcher Dr. Daniel Martin. Drone-based herbicide applications also decreased herbicide use by almost half compared to broadcast applications, but operators must account for drone downwash (the downward draft of air from the spinning propellers) knocking over tall weeds. Researchers note that the detection software needs further refinements to improve the detection of weeds that hide within the canopy or look similar to rice.

Targeted herbicide applications are increasingly important due to their potential for saving herbicide costs, avoiding crop injury, and possibly warding off herbicide resistance. The Texas A&M research comes as the targeted spray industry is getting up to speed in many other row crop production systems, Bagavathiannan notes. “There’s a lot of work being done in row crops with the aim of detecting and precisely applying herbicides on weeds,” he says. “But there is very little, if any, of this research being done in rice, which is a unique production system that poses distinct challenges for weed detection and site-specific management.”

The Mind Behind the Drone

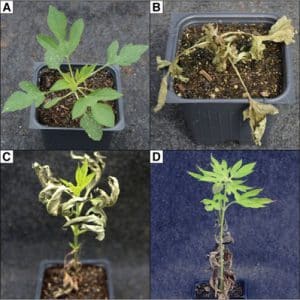

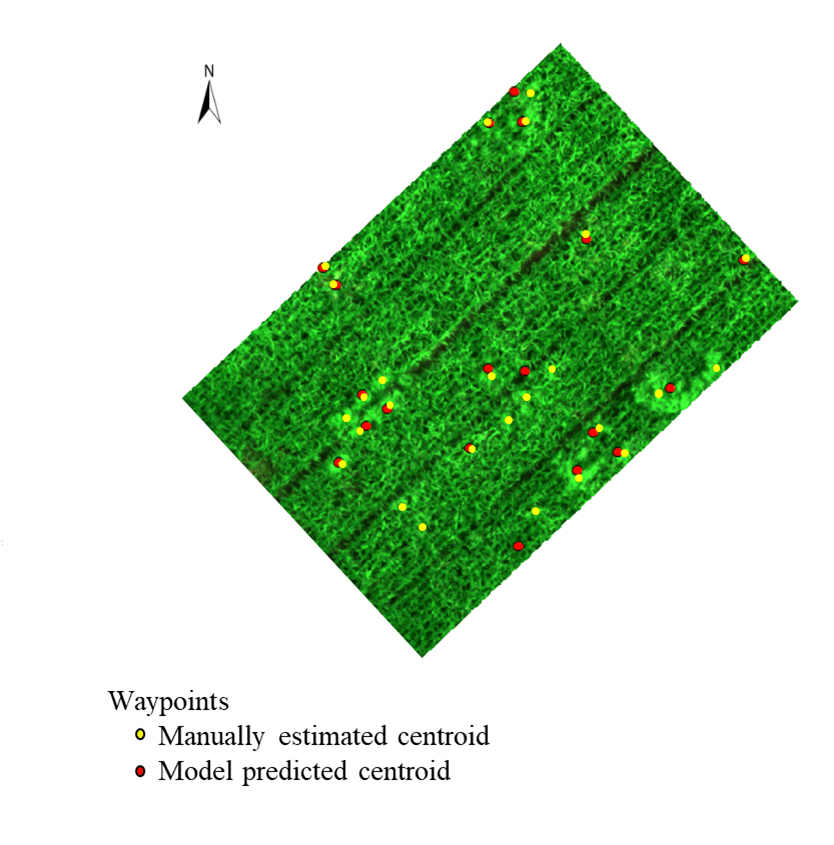

It’s not the drone itself that detects weeds, but an algorithm model trained by Gurjar. Gurjar used images of hemp sesbania, Amazon sprangletop, yellow nutsedge, and barnyardgrass throughout their growth cycle to show the model what to look for in the rice fields. The algorithm can then detect weeds based on their height compared to the crop canopy, and their species-specific light absorption and reflection wavelengths. But the detection system is not without some limitations.

The team found that using drone-captured imagery and algorithms to identify weed patches was consistently up to 10% less accurate than manually flagging weed patches for the drone to fly to and spray. This inaccuracy is a combination of slight differences in an image’s GPS location and the algorithm’s ability to detect the center of weeds in an image versus the weed’s actual structure. These factors caused the drone to sometimes miss its mark by several centimeters.

Still, the image-based model detected 95% of hemp sesbania, 87% of Amazon sprangletop, 74% of yellow nutsedge, and 62% of barnyardgrass with its current training. Weed mimicry, the researchers say, is to blame for the difference in detection accuracy. Some weeds such as barnyardgrass have evolved to look similar to rice prior to seedhead production. This makes any form of detection that relies on imagery – whether through human sight or algorithm analysis – difficult. (Read our article on the potential of weeds evolving mimicry to avoid precise herbicide applications here.)

Another limitation was weed size and location. The drone-mounted sensors easily detected tall and large weeds, but any weeds that hid under or at the rice canopy went undetected.

Nor did the drones quite live up to the thoroughness of a broadcast spray. The drones that sprayed manually-flagged weed patches had 8% less overall weed control when compared to a broadcast application with a backpack sprayer. The image-based drone spray had 23% less weed control than the backpack sprayer.

But the drone-based target sprays still achieved 50% or higher biomass reduction in the treated weeds. The precise drone herbicide applications also resulted in a 45% decrease in sprayed herbicide. Targeted applications minimized rice injury from herbicide, which could give farmers more flexibility in choosing the herbicides they use in rice.

Gurjar also points out that humans still supervise the drone operations, and decide where the spray applications are made. This helps guarantee that herbicide is saved and that no crops get mistakenly caught in the crossfire.

Gurjar continues to improve the model and hopes to conquer weeds that hide in plain sight through mimicry. “We are collaborating with the International Rice Research Institute [Dr. Virender Kumar, Senior Scientist] and we are making a rice-weed dataset,” Gurjar says. “So far we have targeted five to six weed species using A.I.”

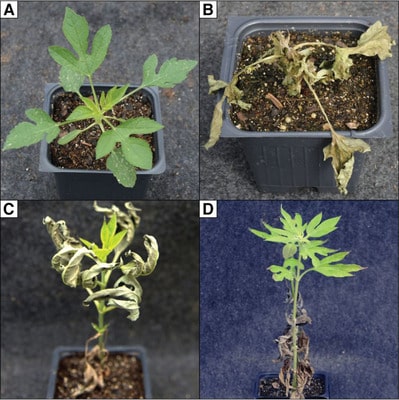

Drone Downwash

Drone downwash is one factor that software improvements can’t conquer. This drone-generated wind lodges weeds, especially with tall weeds such as hemp sesbania. Sprayed herbicide applications can miss parts of weed patches that get blown over by downwash. But for shorter weeds, the downwash can be an added bonus that opens the crop canopy and reveals the mostly-hidden weeds, improving herbicide coverage, Bagavathiannan says.

The drone flew at a fixed 8.2-foot height for their study. Gurjar says that increasing the drone height could help decrease downwash in situations where it’s unwanted, but herbicide drift could be an issue if there are high wind speeds.

Eyes in the Sky

Drones are handy tools even if they aren’t spraying herbicide on weeds. These machines increasingly help farmers scout fields with a birds-eye view, making even traditional weed control easier. Drone imagery can even warn farmers about potential herbicide-resistant weeds in their fields by showing weed patches that may have gone unaffected by early-season weed control, Bagavthiannan says.

Drone scouting and target-spraying capabilities will only advance as researchers such as Gurjar continue to improve the analysis algorithms to better detect weeds. The end goal is to create a tool for farmers that saves money, makes weed control easier, and combats herbicide resistance.

Explore GROW’s website for more information about precision weed management and using drones for targeted herbicide applications.

Article by Amy Sullivan, GROW; feature photo by Bholuram Gurjar, Texas A&M; header photo by Ubaldo Torres, Texas A&M.