Using cover crops for weed suppression can be complicated, so itŌĆÖs little surprise that the past decadeŌĆÖs worth of research on the practice is equally messy.

But several core truths on cover crops and weed control emerged from a symposium held at the Weed Science Society of America’s annual meeting held in Arlington, Virginia on January 31, 2023. There, a large panel of weed scientists and ecologists hashed out the latest cover crop knowledge in the aptly named symposium, ŌĆ£The Good, the Bad, and The Ugly of Cover Crops.”

Here are four takeaways from it:

1. Cover crop biomass is key ŌĆō if you can build it.

Amid the widely varying regional data, one common trend has emerged: The more biomass a cover crop has by termination, the greater the likelihood of successful weed suppression. A thick mat of residue can suppress weedsŌĆÖ germination, emergence and reproduction and even contribute to the decay of weed seeds beneath it, said Dr. Erin Haramoto, a University of Kentucky weed scientist, who led the symposium.

— Dr. Erin Haramoto, University of Kentucky (Photo credit: Claudio Rubione, GROW)“We know that we get more weed suppression from having more cover crop biomass; the more residue, the better the weed control.”

But not all regions can accomplish this consistently. Good luck growing a towering stand of cereal rye by soybean planting time with only two inches of rain between January and June ŌĆō the scenario faced by western Kansas farmers in 2014, explained Dr. John Holman, a cropping systems agronomist from Kansas State University.

And in order to grow 5,000-kg/hectare-worth of cereal rye biomass before soybean planting ŌĆō an amount generally accepted to produce 75% weed suppression ŌĆō your planting date would have to slip deep into late May and early June or even later in Illinois and Iowa and northward, Haramoto added.

ThatŌĆÖs one reason why weed suppressive cover cropping is more attainable in regions where the annual likelihood of warm springs with plentiful rain is higher, noted Dr. Steven Mirsky, a weed ecologist with USDA ARS. ŌĆ£The mid-Atlantic is a generally a region that produces a lot of a good biomass, because weŌĆÖve got both the heat and the moisture,ŌĆØ he explained.

That doesnŌĆÖt mean areas farther north and farther west can see no weed suppression benefits from cover crops, researchers caution ŌĆō but it does lead to the next big takeaway:

2. Farmers need a region-specific cover cropping approach.

For dryland growers in the semi-arid Great Plains, cover cropping every year has obvious risks, Holman noted. In dry years, the cover could rob the ground of precious moisture and leave a cash crop in worse shape. But HolmanŌĆÖs research has also shown that in years with average or above-average rainfall, cover crops can produce many benefits for Great Plains growers including erosion prevention, weed suppression, and livestock forage.

So his research team has developed a Flex-Fallow cover crop concept, which recommends growers only plant cover crops in place of a fallow rotation if a Paul Brown Moisture Probe finds at least a foot of soil moisture and the NOAA Climate Prediction Center is forecasting average to favorable moisture for the season. ŌĆ£We try to take advantage of moisture in the good years and crop less intensively in the dry years,ŌĆØ he said.

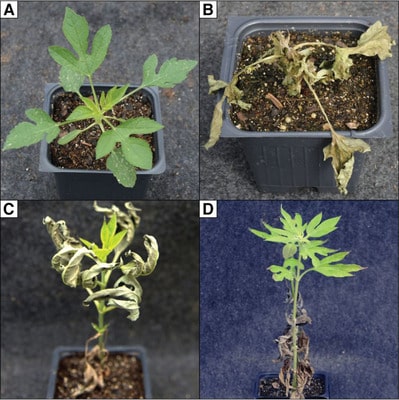

In contrast, in the generally well-watered fields of Pennsylvania, Dr. John Wallace is taking cues from growers in his region who are leading the way on the practice of ŌĆ£planting green,ŌĆØ wherein cash crops are planted into growing cover crops for maximum biomass production.

Researchers at the 2023 WSSA Meeting’s symposium on cover crops (bottom right) agreed that cover cropping for weed suppression requires regionally specific plans, with some options — like roller-crimping and planting green (far left) — viable in mid-Atlantic states, and rainfall dependent plans like the Flex-Fallow Concept from Kansas State University suitable for the semi-arid Great Plains (top right). (Photo credits: Claudio Rubione, GROW and Emily Unglesbee, GROW).

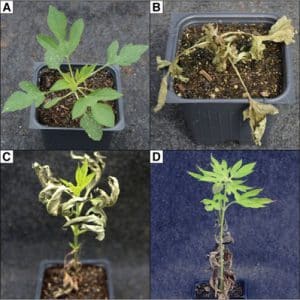

One of the risks of cover crops is the chance that they will become a weed due to weather delays in termination in the spring, Haramoto noted. Wallace is currently leading a GROW research project to see ŌĆō among other things ŌĆō how cover crops might affect the number of ŌĆ£field fitŌĆØ days for planting, by drawing up excess soil moisture in fields at planting time.

Another regional issue affecting cover crop success is the risk of increased pest pressure such as slugs or voles, which can benefit from increased residue and plant material in a field, Haramoto said.

These field-specific factors are behind another GROW project, led by Mirsky, which aims to produce open-source digital weed and cover crop mapping tools, using affordable camera systems like GoPro. Mirsky hopes the resulting field maps will help farmers better understand how practices like cover cropping or fertility programs actually work on their own individual fields.

3. Cover crops canŌĆÖt stand alone as weed control.

Even at their best, cover crops cannot control all weeds, all season-long, Haramoto concluded. ŌĆ£We need a lot of cover crop biomass to get to 80% to 90% weed control,ŌĆØ Haramoto said of recent studies of roller-crimped cereal rye. ŌĆ£Maxing out at 80% to 90% is probably not sufficient for most farmers ŌĆō they will need an additional tool.ŌĆØ

Her fellow researchers and presenters agreed. ŌĆ£Cover crops will never be the totality of weed control,ŌĆØ Mirsky said. ŌĆ£If youŌĆÖre trying to truly reduce the weed seedbank, youŌĆÖll need a holistic effort. The biggest hammers will be the new tech coming our way ŌĆō things like harvest weed seed control and robotics ŌĆō the surgical management of weeds.ŌĆØ

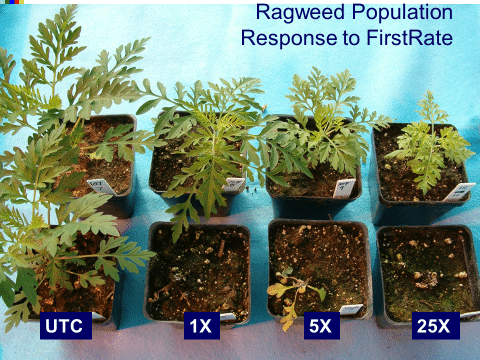

4. We need to learn if cover crops can slow herbicide resistance.

The risks of cover crops ŌĆō increased costs, pests, moisture loss, termination issues ŌĆō are increasingly well established, Haramoto noted.

The benefits ŌĆō weed suppression, soil health, less erosion ŌĆō are getting clearer, as well. But two big questions remain, Haramoto said: Can cover crops truly reduce herbicide use, and do they slow herbicide resistance?

There are hints that they can ŌĆō studies have shown cover crop residue allows fewer weeds to emerge and forces them to be smaller ŌĆō a key step in reducing selection pressure on herbicides.

But weŌĆÖre far from sure of these long-term benefits, Haramoto concluded. ŌĆ£We really need to get a handle on whether we reduce herbicide use and mitigate herbicide resistance, if we want to firm up our message on [cover crop benefits],ŌĆØ she said.

Article by Emily Unglesbee, GROW