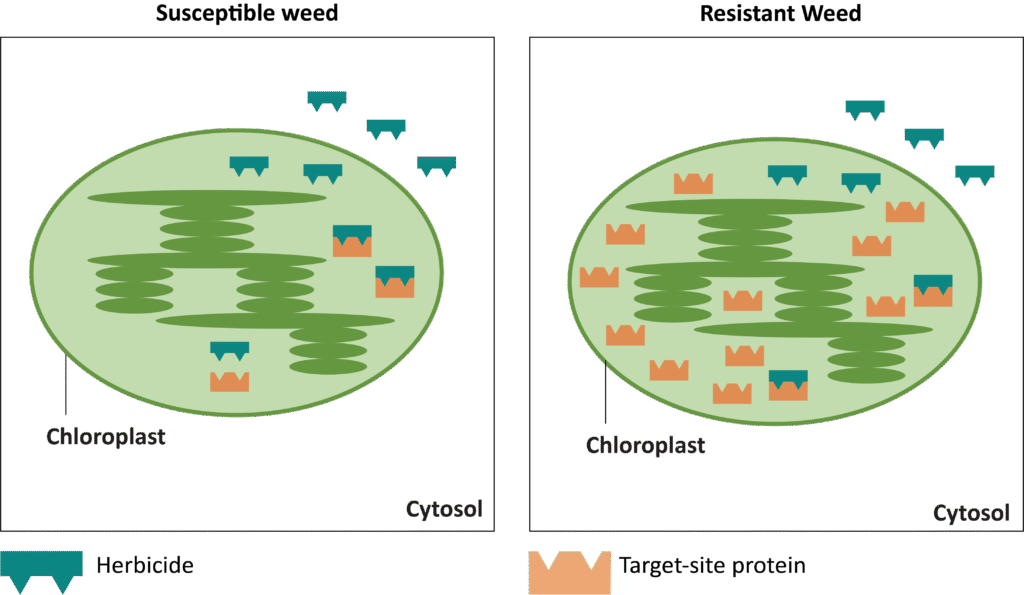

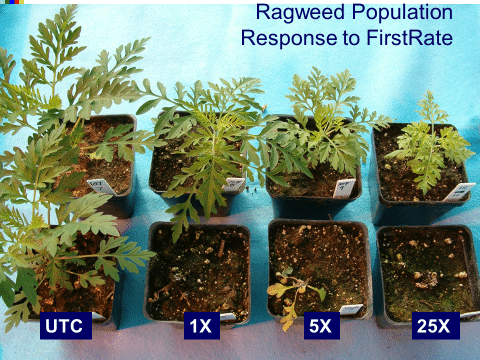

Weeds think they’re pretty smart. Since modern agriculture began, weeds have been evolving and lying in wait to grow again – to the frustration of farmers and scientists alike. They have adapted to resist herbicides and other termination methods to keep reproducing.

Today, researchers are looking at troublesome weeds to find other ways they may be evolving to avoid their demise. Dr. Michael Flessner, a weed scientist at Virginia Tech, is working with colleague Dr. David Haak, a plant geneticist, to learn more about Palmer amaranth and its growing cycle. They are concerned that this weed could flower earlier, and then in turn, disperse its seeds sooner, thus avoiding harvest weed seed control (HWSC) methods. (HWSC includes methods such as seed impact mills, chaff lining, and narrow windrow burning.)

“When weed seed control is applied across broad acres for multiple seasons, we expect the weed species to adapt in some way,” Flessner says. “And there are several ways, including earlier flowering and seed shedding.”

Flessner is being proactive in his work with Palmer amaranth, testing to see how likely this plant can develop these adaptations and, if so, what genetic mechanisms are responsible. He is following in the footsteps of fellow weed scientist and agronomist Dr. Michael Ashworth, who has been conducting similar research with the Australian Herbicide Resistance Initiative (AHRI), at the University of Western Australia, on wild radish, a prolific weed common in wheat fields.

Reading the Warning Signs of Wild Radish

Ashworth is noticing that wild radish – the second worst weed for herbicide resistance in Australia – is flowering earlier than it has historically.

“The important lesson we learned is that a diverse system for weed control is necessary in sustaining HWSC.”

Dr. Michael Ashworth

“Across the board, nearly all species are flowering earlier in response to farming,” Ashworth says. “The plants want to do what’s ecologically optimum. Plants often adjust their flowering in response to temperature, moisture and stress situations to maximize their seed production. When harvest weed seed control is applied, later flowering plants have their seed interspersed and destroyed. Earlier flowering plants can shed more seed before harvest, adding to the soil seed bank.”

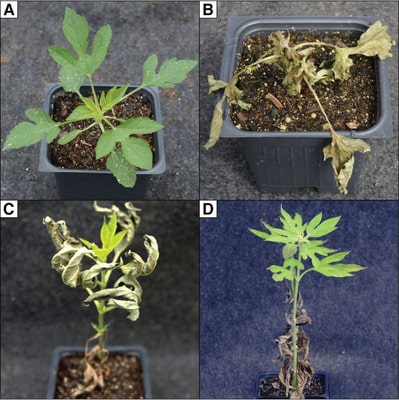

In his research, Ashworth forced the wild radish to halve its flowering time from 52 days after emergence to 23 days after emergence, after five generations of selection. But when the effects of HWSC were modeled using field conditions, the shifts in flowering time weren’t as significant as he expected.

“The important lesson we learned is that a diverse system for weed control is necessary in sustaining HWSC,” Ashworth says. “We want to take any opportunity to put the weed at an ecological disadvantage. Farmers need to maximize crop competition and terminate early-emerging weeds, as they’re the ones that will have the longest lifetime and could flower early. By terminating the early growers, the remaining plants have less of an opportunity to change flowering time to evade harvest weed seed control.”

Staying One Step Ahead of Palmer Amaranth

This research focuses on weeds that have escaped other control methods including herbicide applications or tillage. Integrated weed management (IWM) is crucial to managing these resistant weeds, and adding a HWSC method can boost successful weed termination. But when weeds, like the wild radish, shed their seeds earlier, HWSC becomes ineffective. Ashworth noticed this on several farms, which prompted him to begin his research.

Flessner is hoping this can be avoided in Palmer amaranth. This weed commonly produces hundreds of thousands of seeds per plant and holds onto them after it dies. Without HWSC methods, weeds that go through the combine at crop harvest will distribute their seeds across the field. In several studies, impact mills have proved to drastically reduce this.

“Palmer amaranth has already proven its ability to adapt to farm management with its herbicide resistance,” comments Flessner. “The weed retains at least 90% of its seeds at harvest time, making it a great candidate for HWSC.”

In Virginia, Flessner and Haak have been conducting greenhouse tests to measure the length of flowering time to first seed shatter in Palmer amaranth.

“We wanted to see how day length changed flowering times, so we collected Palmer amaranth populations all along the East coast from Pennsylvania to Florida,” Flessner explains. “The populations from the northern latitudes tended to go from emergence to flower in less time, but there was no geographic difference in the plants for time from flowering to seed shatter.”

The next steps for Flessner and Haak are selective breeding and studying the material extracted from Palmer amaranth to find the genetic controls for flowering variation. Ph.D. student Eli Russell, in the Flessner lab, is cross-breeding the earliest flowering plants and then doing the same with the latest flowering plants.

“We’re forcing them in opposite directions from shorter flowering to longer flowering, and we’ve just planted our third generation,” says Flessner. “We’ve been able to reduce emergence-to-flower from about 90 days down to 60 days.”

The end goal is to determine how likely Palmer amaranth is to adapt and how much genetic variability exists across the landscape, he says.

By finding out when or if weeds are evolving their growth patterns, farmers can adapt accordingly with their integrated weed management plans as well as their harvest weed seed control.

Time will tell – as well as researchers like Ashworth and Flessner.

Read more about harvest weed seed control on this GROW Webpage and in these GROW News Page articles.

Article by Carol Brown; header photo by Eli Russell, Virginia Tech