Last week, we wrote an article on Harvest Weed Seed Control using the Harrington Seed Destructor (HSD). This effective machine works with a combine harvester to capture weed seeds, pulverize them, and spread the destroyed remains back onto the field. However, the HSD can only destroy weed seeds that are still on the plants at the time of crop harvest.

In order to better understand the role of the HSD in the US, researchers in 14 states throughout the Midwest, South, and Mid-Atlantic are studying when our most problematic weeds shatter their seeds in relation to harvest-time, and how that varies across the US.

Over the past two years we have found that some weeds hold onto the majority of their seeds past soybean harvest; specifically species that readily incur resistance. These results are encouraging for the potential of the iHSD and other HWSC methods, because it means that these seeds would be susceptible to destruction or removal during soybean harvest. However, we are also finding that other weeds shed the bulk of their seeds too early to be ideal candidates for iHSD control.

The seed rain study

To study when weeds drop their seeds (also called “seed rain”), we needed to design a method to grow the weeds in the field and collect their seeds as they fall, that would work across all 14 states.

Weed scientists in each state picked out some of the most common weeds in soybeans from their respective states. They then had to find a field that contained all of these weeds, and mark those weeds with flags. The fields were planted into soybeans, and those select weeds were allowed to grow or “escape” through the season. Keeping them safe from herbicide applications required covered them with plastic cups or buckets whenever the field was sprayed.

Around early August, before seed rain began, we removed the soybeans surrounding each weed to give them space to finish growing. Removing interfering soybean biomass ensures weed seeds are not intercepted by the soybean canopy. We then placed trays under the plants to catch the seeds as they drop from the plants. Every week from mid-August until a month after normal harvest time, we used handheld vacuums to collect the seeds on the trays. This way we were able to measure seed rain over time on a weekly basis.

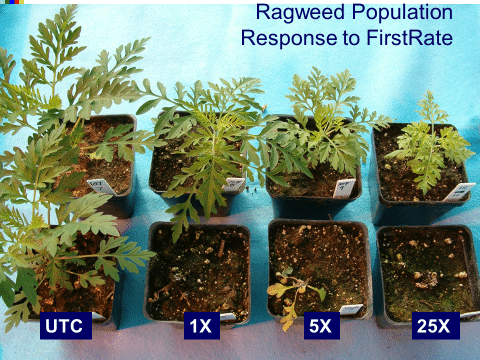

While the work is still ongoing, we have already found that some weeds hold onto the majority of their seeds for a long time past soybean harvest, making them viable candidates for control by the iHSD. Pigweed species in 10 states maintained over 75% of their seeds. In Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, and Mississippi,over 95% were retained. This means that the iHSD would be able to process a great amount of the seeds produced by escaped pigweed.

However, other common weeds dropped seeds more quickly, shedding a large portion before harvest. Several annual grasses, which are known to shed seed earlier in the season, only retained between 30-50% of their seed at harvest in the four states where they were tested (AR, TX, MO, MS). As expected, seed rain patterns also varied greatly by region. This means that HWSC will be a better fit for some weeds, and some regions, than others.

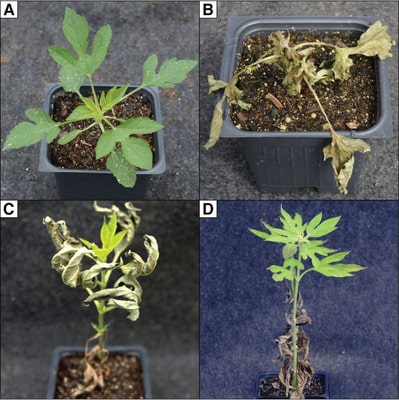

Challenges of keeping weeds alive

While we usually think of weed control as a challenge, roles are reversed in this project as we sometimes struggle to keep weeds alive and well. In order to spray the field without killing our “escaped” weeds, cups or buckets have to be placed over them right before spraying, then immediately removed. We also have to account for insects and small mammals.. Insects sometimes feed one seeds on the trays. Pigweed leaves are also appealing to some insects. Rain was another challenge that caused buildup of water and mud on the trays, making seed collection more time-consuming but not likely affecting our results.

The future of the seed rain study

The Seed Rain study is currently in its third and final year; trays have been set out, and we are collecting seed.

The results will identify which weeds can be potentially controlled by HWSC tactics. A promising result from this study is that many common weeds seem to retain most of their seeds until after harvest, across various parts of the country.

Farmers across the US work with different climates, weed species, and management systems, so the broad geographical range of this work helps us see how HWSC may fit in with our diverse agricultural systems. It is encouraging that we are finding numerous species that are candidates for control by HWSC across these broad geographic regions.

Article by GROW staff